Health services around the globe are struggling to keep up with COVID-19’s sprawling effects. Governments have controversially brought social life to a grinding halt, which has resulted in the sharpest economic contraction since the Great Depression. The medical emergency should be our first concern. However, the indirect impact of COVID-19 on automating the economy is not far behind.

Robotisation, AI, and Industry 4.0 have long been buzzwords. The current crisis is set to bring them into keener focus. Indeed, it is well-established that the pace at which capital replaces routine jobs in the economy accelerates during recessions and leads to subsequent “jobless recoveries”. The underlying logic is quite simple. Ordinarily, firms that want to restructure their production face inhibitive costs associated with laying off workers. However, during recessions the worsening business cycle forces those firms to fire workers to stay afloat. This, in turn, allows management to reset and restructure production in a more capital-intensive way after the crisis. Some early signs suggest that this process is already underway. A recent survey by EY reported that some 36% of global executives are accelerating investment in automation as a result of COVID-19 while a further 41% are planning to do so.

Drastic changes in production invoke social conflict even in the best of times. This time around, as governments pull their economies away from an unprecedented depressionary cliff, policymakers have good reason to rethink the negative effects of labour-replacing technological change. To be sure, firms should not be prohibited from investment to improve productivity. Quite the opposite, as part of their countercyclical efforts, governments should seize this moment to invest in firms’ health and to future-proof their industries.

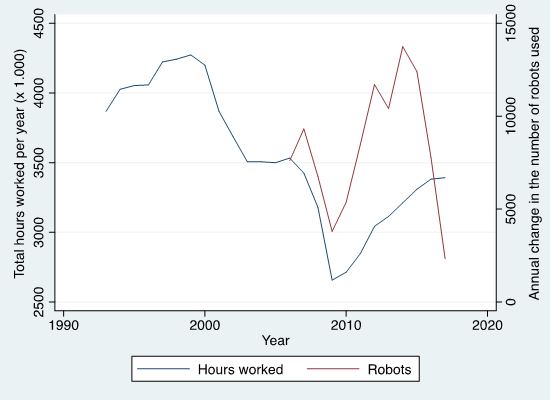

We should prioritise an inclusive form of automation that ensures worker protection and does not repeat past mistakes. President Obama’s 2008 car industry bail out, for example, has a particularly mixed record. The bailout saved jobs in the short run and guaranteed pay for unionised car workers even when plants closed. However, much of the automotive sector was quick to invest in retooling and automating its plants. This has left many blue-collar workers with a bitter aftertaste regarding the taxpayer-funded bailouts. Indeed, between 2008 and 2010, the ratio of robots to every 10,000 workers in the US automobile industry jumped a massive 50%, which left no doubt about the severe social costs of more capital-intensive production. Figure 1 further demonstrates this point: the red line illustrates the US automotive sector’s spike in robot purchases between 2008 and 2014. The blue line illustrates that employment, on the other hand, took a dive and settled close to its pre-crisis level only a decade later. While that recovery might seem like a victory in the end, we need to help workers through the transition while it happens. Let Keynes’ warning that “in the long run we are all dead” serve as a reminder; jobs that re-emerge 10 years on mean little for households struggling now.

Figure 1. Hours worked and annual change in number of operational robots in the US automotive sector

How should we manage this transition into further automation? I argue governments should ensure that investment into labour-replacing technology, over the coming years, does not leave workers behind. This would mean either offering incentives to firms that guarantee workers’ employment or forcing companies to continue paying displaced workers’ wages. It would also mean creating generous retraining programmes, both to upskill incumbent workers and to offer opportunities to those otherwise left behind. One of the key problems with labour-replacing technological change is not that it leads to a slump in aggregate demand for labour, but rather that it eats away at routine jobs. Meanwhile, the new jobs that re-emerge tend to be more skill-intensive and potentially unattainable for workers that just lost out. Promising examples include Marlin Steel, which retrained its workers to operate in the new production environment.

Inclusive automation is paramount for at least two reasons. First, we need to safeguard wellbeing, especially for those who are already vulnerable. Research suggests that automation and subsequent labour-market polarisation have caused havoc in many communities over the last decades, and might be a key driver behind populist resurgence. Disregarding the prosperity of these communities is therefore neither morally nor politically affordable.

Second, we need to confront the macroeconomic puzzle. As governments and central banks around the world mount enormous fiscal and monetary efforts to jump-start global demand, it would make little sense to depress worker consumption further by layering a second, technological, shock on top of the first. In fact, further subsidising firms’ technological transitions (be it through direct fiscal intervention or indirect monetary policy) without also socialising the potential negative by-products would be a political and economic worst-case scenario.

The feasibility and success of different responses will vary depending on many factors. The top of the list includes fiscal space; existing welfare state generosity; and the extent of institutionalised cooperation between workers, capital and government. Indeed, furloughed workers in Germany, who enjoy excellent skills profiles and board-level representation, will be much better placed to strike fair bargains compared to their US counterparts, many of whom have already lost their job and will be left relatively powerless.

The most likely outcome of COVID-19 will include an increasingly-automated production system (Carl Benedikt Frey has another take). This is far from a bad thing. Process innovations have historically been levers towards increased welfare and have eased the burdens of many unpleasant tasks. However, we should ensure that a more automated world does not leave workers behind. Let us therefore enact a truly inclusive form of automation.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the Social Policy Blog, nor of the London School of Economics.