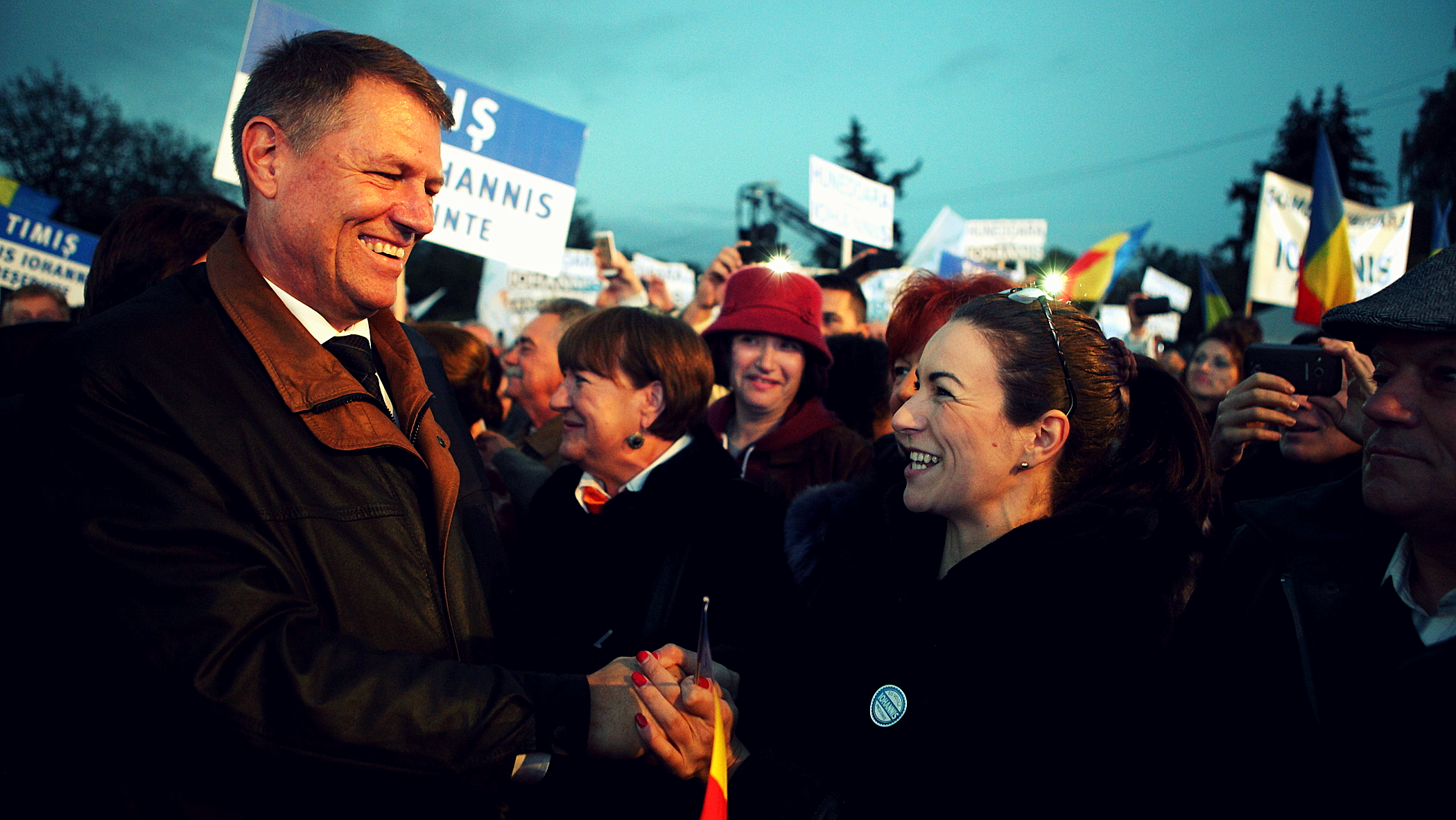

Klaus Iohannis (or Johannis? Spelling does matter, in this case): Sibiu mayor, ethnic German, known to keep order in a nice town, a Transylvanian. It should not come as a surprise that the Hungarian minority voted for him. And yet, the whole picture is more complex: Sherrill Stroschein disentangles the riddle behind the Hungarian ethnic vote in Romania. To find out more about the Romanian elections, come to our panel debate on Monday, 1 December.

Klaus Iohannis (or Johannis? Spelling does matter, in this case): Sibiu mayor, ethnic German, known to keep order in a nice town, a Transylvanian. It should not come as a surprise that the Hungarian minority voted for him. And yet, the whole picture is more complex: Sherrill Stroschein disentangles the riddle behind the Hungarian ethnic vote in Romania. To find out more about the Romanian elections, come to our panel debate on Monday, 1 December.

One of the most interesting aspects of the recent Romanian presidential election has been the dynamics of the ethnic Hungarian vote. Ethnic Hungarians have not featured in much of the English-language discussion on the elections, likely due to their 7 percent share of Romania’s population. However, for those interested in ethnic politics, the Hungarian voting in this election demonstrates some fascinating patterns that show up some holes in the standard ethnic politics literature.

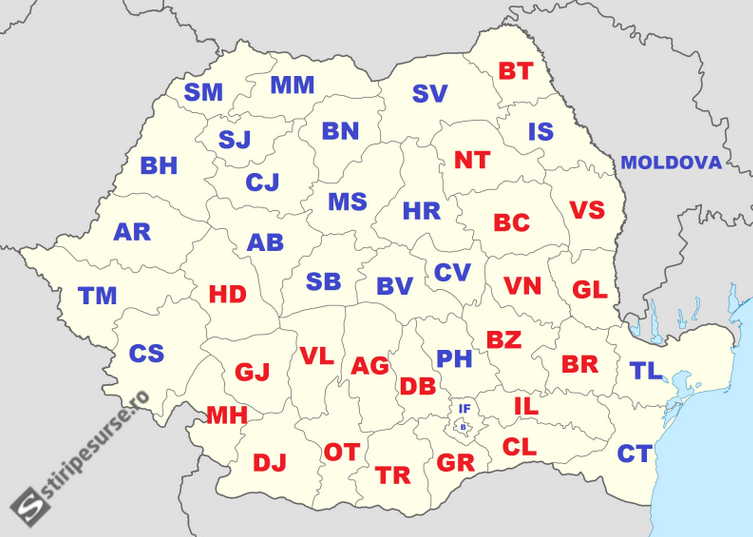

Much of the work in political science on ethnic politics tends to treat an ethnic minority as a unit or a unified group (even an “actor” or a “rational actor”). This post has done so as well by using the “ethnic Hungarian” moniker for simplicity. But Hungarians in Romania have vastly different interests depending upon their local demographics. “Politics is local” is a useful phrase when considering these differences. Hungarians in Romania are concentrated in Transylvania, but within Transylvania some live in Hungarian enclaves, where Hungarians make up more than half of the town or city population. Many of these enclave communities lie in the counties of Harghita and Covasna, a mountainous Hungarian island in the center of the country with Hungarian concentrations of over 80 percent and 70 percent, respectively. Some portions of Mureş county also fall within this enclave definition. Many Hungarians living in the enclave would like to pursue a goal of territorial autonomy for this region. For the other set of Hungarians living outside of this enclave, potential autonomy is a project that they do not see as benefitting them, as they live outside of the enclave where it would be established.

This cleavage is reflected in the fact that two different Hungarian parties, the RMDSz / UDMR (Democratic Union of Hungarians in Romania) and EMNP / PPMT (Hungarian People’s Party of Transylvania), each proposed candidates for president in the first round of elections. The EMNP, a relative newcomer to politics, tends to have more support in the enclave regions and tends to endorse the autonomy agenda. The RMDSz, which has been a political actor since 1989/90, presents itself as a pragmatic entity that has managed to cooperate with various Romanian governments and place itself in governing coalitions. As such, it has not actively endorsed autonomy since the late 1990s.

In spite of this fragmentation, Hungarian voters have a pragmatic side. Against expectations of a large EMNP win in the local enclave elections in 2012, the RMDSz instead did quite well. This was even the case in the context of a large resurgence of local (Székely) identity in the enclave. Székely light blue-yellow flags are an increasing presence, as are Székely symbols and these colors. Perhaps pragmatism can win votes where there are other outlets for sentiment.

However, Hungarian support for the RMDSz did not carry into the 2014 presidential election. The RMDSz has tended to put their own candidate forward in the first round of presidential elections as a show of sentiment and numbers – a way to make the Hungarian voice visible in Romanian politics. Typically, the RMDSz candidate would then endorse a candidate for the second round, with the idea that it would be clear to that candidate how many Hungarian votes had been brought forward by the party, and with the hint that Hungarian interests should be considered by that candidate as president. With the EMNP’s running of a candidate as well, the act of presenting a unified Hungarian voice was compromised – the RMDSz candidate Kelemen won 3.47 percent and the EMNP’s candidate Szilágy won .56 percent in the first round. This fragmentation weakened the potential endorsement that could follow for the second round.

But it was in the second round that the internal drama became really interesting, as a result of the interaction of the tensions outlined above. The RMDSz, which had a good working relationship with Ponta in government, made a weak statement that it was not endorsing Johannis, and that each Hungarian had to vote their own conscience, a phrase they used for Ponta’s attempt to impeach Băsescu as president by referendum in 2012. In contrast, the EMNP openly endorsed Johannis. The election results by location decisively show that the ethnic Hungarians ignored the RMDSz and voted enthusiastically for Johannis. If one steps aside from the political churn a bit, this is absolutely not surprising. Sibiu mayor, ethnic German, known to keep order in a nice town, a Transylvanian. Of course the Hungarians would vote for him, and the electoral map shows that the rest of Transylvania joined them, in contrast to other regions. Some commentary that followed argued that the RMDSz lost sight of these ideas because of its focus on power, and thus forgot the interests of Hungarians.

While it is useful in many cases to examine the acts of the RMDSz and the EMNP through an ethnic party lens, a bit of thinking outside of this box can explain what some are calling the RMDSz “failure” in the presidential election. The RMDSz is not just an ethnic party – it is also a swing party. Since 1996 when it first joined a government coalition (though it was briefly involved in the post-revolutionary National Salvation Front governing structure between late 1989 and the first elections in 1990), it has got things done in government by playing different groups off of each other. Small parties have to do this if they plan to play politics at the level of the country’s capital.

In the UK, the Liberal Democrats have found this out as well. Taking part in the Coalition with the Tories has gained the Liberal Democrats much in terms of politics that matters at the central level, but at the expense of the ideals of many in their membership. Politics is a dirty business. But the analogy may break down with ethnic parties. An ethnic party appeals to ideals that have a solid base in identity. As an American living in the UK, I have had to conclude that the Liberal Democrats are an extremely committed lot – but what they are committed to seems to vary greatly according to who you ask. This is not the case for an ethnic party – it is possible to point to language, culture, symbols, history, and concrete political goals as linked to the identity of the ethnic group as a standard. This is where the EMNP comes in – and it challenges the RMDSz legitimacy in claiming to represent that identity. It would be pure hubris to predict what will happen next for these parties going forward, but I would wager that these themes will emerge again and again.

As a side note, is the new president named Johannis or Iohannis? For Hungarians, the notion of being able to use his own name (Johannis) free of the Romanian spelling (Iohannis) resonates strongly. Hungarians continue to use their own names for locations throughout the region, and language and naming remain a crucial part of Hungarian identity. The fact that this issue even emerged at all during the campaign is one that could have brought strong Hungarian support. It remains to be seen whether the new president identifies as a minority or whether he simply plans to be president. For Rudolf Schuster in Slovakia, the ethnic issue seemed to play only a marginal role. If this is disappointing to the Hungarians, it will come with the consolation that Romania has an admirable post-ethnic aspect to its contemporary politics. As such, it can be a light of progress for states that have not seen a productive way through identity questions, including some of those in the West.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

______________

Sherrill Stroschein – LSEE Research on SEE, LSE & UCL Department of Political Science

Sherrill Stroschein is an Associate Professor in Politics in the Department of Political Science at University College London, and director of the master’s program on Democracy and Comparative Politics. Her publications examine the politics of ethnicity in democracies with mixed ethnic or religious populations. Her latest book is Ethnic Struggle, Coexistence, and Democratization in Eastern Europe.