The outcome of the Romanian presidential elections has been nothing short of surprising: underdog candidate Klaus Iohannis beat the incumbent prime minister and favourite, Victor Ponta, with a very convincing result. Daniel Brett and Eleanor Knott take us through the whole story and get ready to discuss Where does Romania go from here at our event on 1 December.

The outcome of the Romanian presidential elections has been nothing short of surprising: underdog candidate Klaus Iohannis beat the incumbent prime minister and favourite, Victor Ponta, with a very convincing result. Daniel Brett and Eleanor Knott take us through the whole story and get ready to discuss Where does Romania go from here at our event on 1 December.

“Mândru că sunt român ortodox” / “Proud to be Romanian Orthodox”

Victor Ponta, Romanian Prime Minister and PSD Presidential Candidate

This weekend’s Presidential Elections in Romania produced a result that has taken many observers in Romania and the West by surprise. The incumbent Prime Minister Victor Ponta of the Social Democratic Party (PSD) was defeated by Sibiu mayor (and ethnic Saxon) Klaus Iohannis of the Christian-Liberal Alliance (ACL). Iohannis’ victory was convincing (~55% by early polls) and shocking as many of those observers on the morning of the election were predicting an easy and decisive win for Ponta, putting Ponta up to 8-10% ahead of Iohannis.

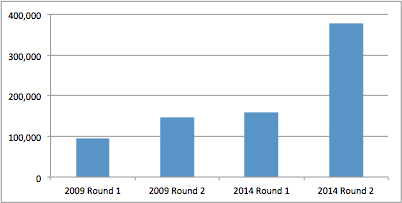

Turnout was high: about 64% of eligible Romanians voted in the second round on Sunday, compared to 57% in the first round and an average of 53-57% in elections since 2000. Particularly mobilised to vote was the Romanian diaspora, with over twice as many voting in the second round as the first and echoing the trend from 2009, when the turnout of Romanians abroad voting doubled (Chart 1).

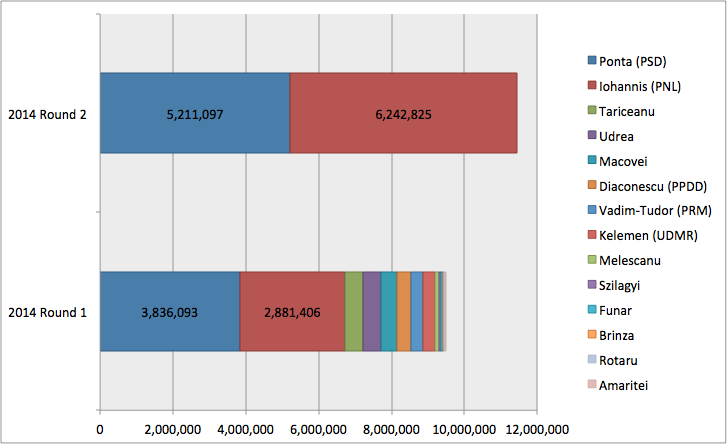

Between the first and second round, not only did turnout increase, pushing the numbers of both Ponta and Iohannis up, but Iohannis was able to consolidate gains from the other eliminated candidates (Chart 2). Ponta was only able to increase his vote share by 5%, while Iohannis was able to increase his vote share by 25% (from 30% to 55%). Iohannis also increased the number voting for him by over two times, essentially sweeping up the votes from the other eliminated candidates.

So, why did Iohannis win and why did no one see this victory coming?

Ponta became leader of the PSD (the Social Democrat Party) after Mircea Geoana was defeated by Traian Băsescu (Romanian president 2004-2014) in the 2009 elections. As leader of PSD, the party occupied a strong position with a large, disciplined, well-developed and organised party infrastructure from a grassroots level across Romania, his task of being elected should have been easy.

As Prime Minister, Ponta had manoevered PSD to control key state institutions overseeing the running of the election. He was able to maintain a prominent media profile, aided by the vociferous support of several television stations. PSD also controlled the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, under Titus Corlățean, thereby controlling the allocation of voting facilities abroad. Romanian diaspora had consistently supported opponents of the PSD and were key in securing Bǎsescu’s victory in 2009, even though PSD/Geoana won the domestic vote.

By comparison, Iohannis had to overcome the implosion and fracturing of the centre right parties as well as his regional rather than national profile, his lack of charisma and his ethnicity, all of which seemed to provide barriers to his election. Secondly, there were more candidates in the first round of the election (14) than since 1992. This included the four centre right candidates, Iohannis, Udrea, Macovei and Tǎriceanu, who originated in the same parties (P-DL and PNL) but decided to run for separately after a series of vicious internecine party conflicts, splitting their electorates.

Ponta was able to win the first round convincingly (40%), leaving him a position that he only needed to gain just over 10% from somewhere, with 30% of the votes up for grabs. Alternatively he could assume that the supporters of the defeated candidates would stay at home in the second round, something that seemed likely given the internecine warfare that had plagued the centre right in recent years.

However PSD’s strength also rendered it toxic to many Romanian voters. As a successor of the National Salvation Front (NSF), who seized power from the Romanian Communist party in 1989, PSD served as a reminder of Romania’s authoritarian past and intolerant tendencies. This was not helped by the way PSD had behaved in government. Ponta did nothing to remove the toxicity surrounding himself and PSD during the campaign.

PSD’s campaign served to reinforce the view that it was the same old PSD, with a populist spin advocating publically for the “second great unification” of Romania and Moldova by 2018. This is nothing new: Bǎsescu and his predecessors have all invoked the nationalist reunification card to inspire votes, both at home and among Romanian citizens in Moldova (of whom 36,000 voted in the second round, twice that of 2009), however, never with a specific timetable nor have they made it a central plank of their discourse. Secondly, Ponta made slurs against Iohannis, as not a true Romanian because he belonged to an ethnic minority. Ponta sought to exploit religious identity as a marker of difference between himself and the Protestant Iohannis and to use it to mobilise the Orthodox rural population, frequently appearing alongside members of the Orthodox Church. The Church in return backed Ponta and told voters to support Ponta. Similarly, attempts to give voters material gifts were also seen as a transparent attempts to buy votes.

However, it failed, in one example PSD supporters openly campaigning in the Orthodox Church with the support of the Priest in Paris were heckled in a video that then went viral.

These appeals to populism had the opposite of the desired effect, Ponta was seen as crude, unreliable and opportunistic, rather than astute. They failed to change the negative perception of the PSD to Romanian society. As the satirical website Times New Roman argued, Ponta achieved something no one thought possible: to make himself more hated than Adrian Nǎstase (Romania’s Prime Minister 2000-2004). Anger and fear over what Romania might become under Ponta served to galvanise Romanian civil society and in turn to mobilise the electorate to go out and vote.

Secondly, the first round of the elections did not go to plan, as the large Romanian diaspora found itself unable to vote as huge queues appears outside embassies and official bureaucracy slowed the process to a crawl. After waiting for several hours to vote, thousands were turned away as the polling station doors were closed at 9pm sharp. Near riots followed and the police were called in London and Paris.

Angry voters outside the Romanian Embassy in London shortly after the Embassy Staff shut the doors on voters waiting to cast their ballots during the first round. Video courtesy of Ioana Dumitrescu

Where does this leave Romania?

Restricting the rights of people to vote has a pertinent message in Central and Eastern Europe with the anniversary of 25 years since the fall of Communism. Romanian voters in Munich took their toothbrushes to the queue to ensure they could vote the next day. Crowds gathered in central Bucharest holding flags with a hole removed, exactly as they had done at the fall of Communism and the Ceausescu regime at the end of 1989.

Hence, with an ‘emerging pattern of soft semi-authoritarian rule in Central and Southeastern Europe, most strikingly in Hungary and perhaps also Macedonia, there is perhaps a sigh of relief among other EU member-states that elections still matter. As Florian Bieber argues, while these semi-authoritarian politicians, like Victor Ponta and Viktor Orban, are able to ‘manipulate and use state resources to their advantage, they still have to win on election day’.

It is an important message to learn that politicians still have to be able to appeal to their electorates, at home and abroad, to legitimise their right to govern because voters are listening, and responding, to the choices made by those in power. In political science, there has been a long debate about the relative merits of presidentialism vs. parliamentary systems, leading to the conclusion that it is perhaps presidential systems that allow more authoritarian tendencies to remain by concentrating a large degree of power in a single office. However elections demonstrate that not all candidates that are able to manipulate the office of prime minister, and benefit from the electoral geography of parliamentary elections, can foster enough public support to be elected president by a majority of the electorate.

Still, Iohannis has a lot of work to do, to live up to the expectations of those who voting him into office. He is inheriting a regime that saw two attempted impeachment referenda, multiple coalitions and a fracturing of the centre right. He has vowed to resign should an attempt to impeach him be called, yet the promises you make out of office, as Ukraine’s new President Petro Poroshenko is fast learning, are nothing compared to the decisions and favours you make once in office. His plans to reduce the size of parliament as well as his desire to reject the political amnesty law for corrupt politicians is likely to put him on collision course with powerful vested interests who will resist any efforts to reign in their power leading more conflict and political instability.

The political landscape remains difficult to predict, whether Iohannis can create a stable party organisation to support him or whether he will have to depend on the goodwill of the fractious and egotistical centre-right remains to be seen. Similarly how the PSD will react to this defeat is impossible to predict, and finally, whether the popular mobilisation despite the anger at the lack of choice in economic programmes will lead to the creation of a new left alternative also remains to be seen. It is likely that parliamentary politics will remain highly volatile in the short term, especially if anti-corruption and reform efforts threaten established vested interests, just as cases elsewhere in the region, such as Ukraine, demonstrate: it’s one thing to win thing to win an election, it’s another thing to govern and meet the expectations of the electorate.

Where Romania goes from here, is something we’ll be discussing further on 1 December at LSEE’s event analysing the 2014 Presidential elections, organised in collaboration with the Romanian-Moldovan Research Group.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

_______________________________

Daniel Brett – Open University

Daniel Brett is an Associate Lecturer at the Open University, he has previously taught at Indiana University and the School of Slavonic and East European Studies. He works on contemporary Romania, rural politics and historical democratisation.

Ellie Knott – London School of Economics

Ellie Knott is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government at LSE researching Romanian kin-state policies in Moldova and Russian kin-state policies in Crimea. She tweets @ellie_knott

Iohannis does have a lot of work to do, even before taking office. The overwhelming feeling in the lines of diaspora voters, in London at least, was that a vote for Iohannis was more a vote against Ponta than one in support of the president-elect’s manifesto. Social media coverage seems to back this up — the volume of anti-Ponta campaigning appears to far outweigh the volume of pro-Iohannis campaigning.

If Iohannis was simply the alternative to the increasingly unpopular incumbent Prime Minister in this election, then his task now is to show the electorate that the alternative he’s offering is one worthy of voting for in itself.