The fifth anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students from a teacher-training college in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, serves as a reminder of Mexico’s long history of violence against its youth. As in the cases of Tlatelolco, El Halconazo, and femicide in Ciudad Juárez, the ongoing vulnerability of certain groups of Mexican young people is enabled by structural inequalities, prejudice, impunity, and processes of stigmatisation, writes Sylvia Meichsner (The Open University).

The fifth anniversary of the disappearance of 43 students from a teacher-training college in Ayotzinapa, Guerrero, serves as a reminder of Mexico’s long history of violence against its youth. As in the cases of Tlatelolco, El Halconazo, and femicide in Ciudad Juárez, the ongoing vulnerability of certain groups of Mexican young people is enabled by structural inequalities, prejudice, impunity, and processes of stigmatisation, writes Sylvia Meichsner (The Open University).

The “war on drugs” declared in 2006 by former Mexican president Felipe Calderon increased the availability of weapons in the country and altered the web of complicated interactions between state forces, organised crime, and civilians. This in turn caused the number of violent deaths and disappearances in Mexico to skyrocket, with young people disproportionately affected.

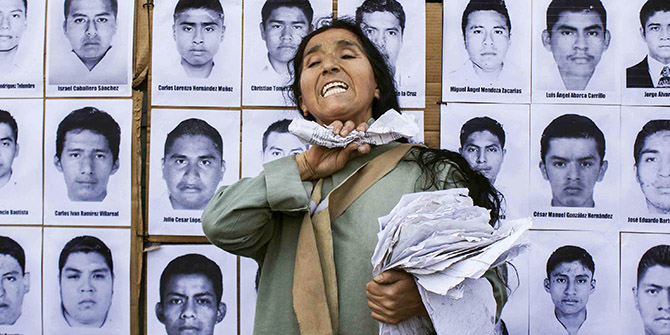

Perhaps the most notorious reflection of this is an incident that occurred five years ago today, on 26 September 2014, and involved a group of students from Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College in Ayotzinapa. Essentially, buses carrying the students towards Mexico City were ambushed by local police in the town of Iguala. Three of their number were killed on the spot, as were three individuals unrelated to the school or to the students. Ultimately, 43 students disappeared without a trace.

Youth killings and disappearances in Mexico: a history of violence

As in many other Latin American countries, violent killings and disappearances of young people have happened before in Mexico, with some more notorious than others.

In 1968, for example, student protests at Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Mexico City’s Tlatelolco district ended in a bloodbath when the armed forces fired on unarmed civilians. The exact number of deaths still remains uncertain, but it is generally considered to run into the hundreds. Then, another major student protest in 1971 led to the Corpus Christi Massacre (El Halconazo), with civilians fired upon by members of a paramilitary group that would ultimately escape punishment. Elsewhere, Ciudad Juárez – the town linked to El Paso across the Mexican-American border – enjoys the very dubious honour of being known as the global capital of femicide, with few perpetrators ever facing punishment for the city’s thousands of murders of women (since the 1990s alone).

Mexican victims’ groups report the forced disappearance of loved ones, typically young people, all across the country.

Stigmatisation and violence

While these incidents might first appear to be unfortunate but unrelated dangers in a violent country, closer inspection reveals recurring patterns and enabling structures. Youth killings are systematic and constant, as is the fact that the perpetrator typically remains unpunished. The act of killing is only the final point of a long process that takes place in an environment conducive to its unfolding. What brings this process to culmination in the actual deed of killing a young person is the tacit assumption that some lives are of so little value that they can be taken without consequence.

Stigmatisation and devaluation of such lives can involve individual characteristics like gender, sexual orientation, ethnic belonging, or social class. Coming from a borough with a negative reputation, however stereotypical that reputation might be, may then result in further stigmatisation and prejudice, and ultimately young people can come to be seen as an “internal enemy”. Stigmatisation of any one of these kinds can have an impact, but they also mutually reinforce each other. The degree of intensity of this stigmatisation is modulated by the social norms prevailing at any given time.

Stigmatisation of certain groups can be also reinforced and perpetuated by simplistic and inaccurate stereotyping in the mass media and cultural industries. Young people within stigmatised groups are then at risk of internalising these stereotypes and reproducing them in their behaviour, be it by accident or by design. The rejection and fear that this can provoke in others then translates into a range of overt and covert expressions of aggression. These can range from a delay in processing paperwork or an unwillingness to properly investigate a crime to intimidating treatment or – in the most extreme cases – the denial of basic human rights, including the right to life itself.

Precarity and vulnerability

The wider context in which this process unfolds also makes the individuals concerned more vulnerable, with various forms of precarity robbing them of effective defence mechanisms.

Low incomes mean few material resources are available, and this combines with stigmatisation and devalued identities to generate legal precarity. Essentially, individuals belonging to specific social groups do not enjoy the same ability to make themselves heard and to demand justice when crimes are perpetrated against them. This means that breaches of their rights are less likely to be prosecuted – even human rights violations and crimes under international law – which leaves them facing an especially high degree of impunity in contexts where impunity is already the norm.

Thus, a vicious circle emerges that results in the banalisation of violent crime: it happens so often and with so few consequences that it becomes a day-to-day occurrence like any other.

At the root of the different types of precarity at play here are structural inequalities that benefit some at the expense of others. The students of Raúl Isidro Burgos Rural Teachers College in Ayotzinapa, sometimes considered “the cradle of Mexico’s social conscience”, were largely the children of poor farmers from Guerrero State. This state is one of Mexico’s poorest and most violent, with a majority indigenous population.

The college aims not only to train its students to become primary school teachers in rural communities but also to raise their awareness of the structures facilitating and reproducing inequality. Alumni are expected to act as community leaders and role models, spreading the knowledge and understanding that they have acquired in order to serve as agents of change and multipliers of social awareness.

In short, their socioeconomic background makes them materially vulnerable, and the political activism involved in their education leaves them open to stigmatisation as “troublemakers”.

Impunity and Ayotzinapa

Though the then-president Enrique Peña Nieto immediately came under massive pressure over the role of factors like impunity and corruption in the Ayotzinapa disappearances, it took a change of presidency and nearly five years for a Special Investigation and Prosecution Unit to be established. This unit has a mandate to collect and analyse evidence in order to provide the best possible approximation to justice for the victims and their families, but in the meantime it was left to the families themselves to search for the disappeared. In practice they often accidentally unearthed the remains of other missing individuals while only rarely finding any trace of those they sought.

The longstanding and persistent lack of any clear official account or accountability, which leaves victims’ families unable to fully lay their loved ones to rest, is a further testament to the legal precarity of the dead and disappeared youth of Mexico.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting