Like other low- and middle-income countries, Colombia introduced changes to its cash transfer programmes so as to mitigate the impact of the COVID-19 crisis. But without extending and carefully redesigning these programmes, many families and young people will face a precarious future once the pandemic is over, write Alejandra Álvarez-Iglesias (Universidad Autónoma de Madrid), Philipp Hessel (Universidad de los Andes, Bogotá), Annette Bauer (Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, LSE), and Sara Evans-Lacko (Care Policy and Evaluation Centre, LSE).

In Colombia, as in many other low- and middle-income countries, cash transfer programmes have become a key instrument in providing social protection and have produced many positive effects on different dimensions of human wellbeing. With the pandemic threatening to push an additional 150 million people globally into extreme poverty by the end of 2021, many of these programmes have been extended to cushion the impacts. But what happens once the immediate COVID crisis is over?

Colombia’s cash transfer programmes: Families in Action and Youth in Action

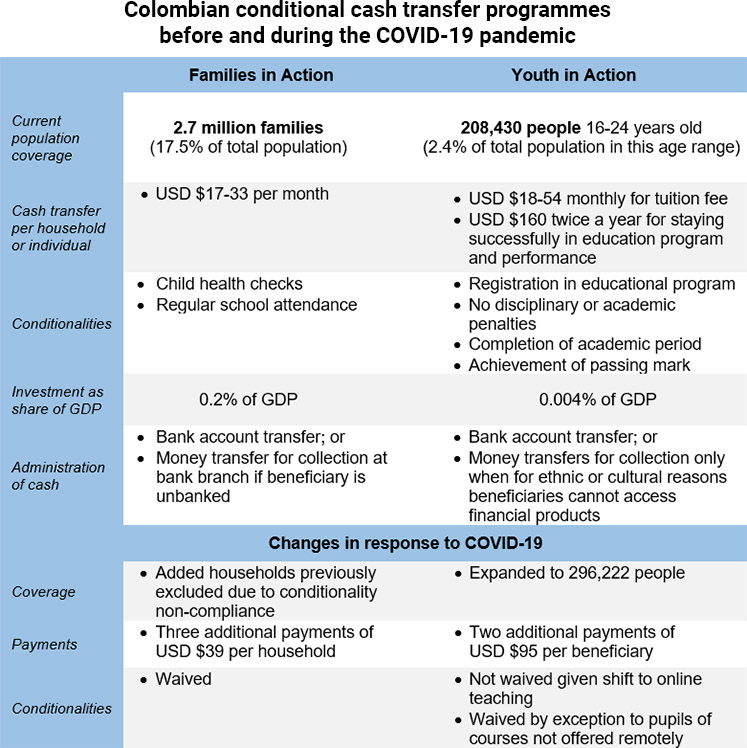

Colombia’s two largest cash transfer programmes, Families in Action (Familias en Acción) and Youth in Action (Jóvenes en Acción), were both introduced in 2000, going on to become key social protection measures in the country. The two programmes provide cash payments to families and young people identified as living in poverty, with individual or household eligibility assessed via a proxy means-test. In line with their stated aim of promoting children’s health care and education, these programmes also ask beneficiaries to comply with certain behavioural conditions in order to receive payments, which is why the “in Action” programmes are considered conditional cash transfer programmes (CCTs). Compliance with these conditions is monitored through an administrative platform that uses data from school and health systems.

Targeting families living in extreme poverty with at least one child aged 0 to 18 years, Families in Action is by far the largest social protection programme in Colombia, reaching around 2.7 million families and about 10 million individuals. In recent years, the programme has also been an important vehicle for addressing the needs of new migrant families from Venezuela. The initiative provides a monthly cash transfer of roughly USD $17 to $33 depending on the number of children in the household and conditional on the regularity of their school attendance, health check-ups, and vaccinations.

Youth in Action incentivises young people (18 to 24 years) to enter and complete higher education by offering contributions to their tuition fees (between USD $18 and $54 per month) and direct cash payments (USD $160 twice a year) conditional on successful continuation of a given course of studies. Youth in Action seeks to provide follow-on support for young people that grew up in households receiving assistance from Families in Action, though it does also support other young people whose families were not involved. The programme reaches nearly 300,000 young people.

Families in Action and Youth in Action during COVID-19

By expanding both their population coverage (horizontal expansion) and the monetary value of their support (vertical expansion), both programmes have also played an important role in addressing the economic and social challenges presented by the COVID-19 crisis (see summary table below).

The eligibility threshold for Families in Action was lowered, bringing in many households identified by the system as economically “vulnerable”. In addition, families previously excluded over failure to comply with conditions were quickly re-enrolled, as their details were already in the programme’s database (SISBEN). The amount of cash transferred to each household rose by USD $39 per quarter. Since programme conditions were made far more difficult to meet by the government’s own lockdown, the programme also temporarily waived its usual conditionalities.

With youth unemployment in Colombia rising substantially, Youth in Action widened its age coverage to reach new beneficiaries (now between 18 and 28 years old). Though this move was planned prior to the pandemic, its implementation was fast-tracked, and officials plan a further expansion that will bring in an additional 200,000 young people. An extra one-off payment of USD $95 has also been made to existing beneficiaries. Unlike for Families in Action, conditionalities for Youth in Action were not waived, however, as most higher education courses transitioned to online teaching relatively quickly. Exceptions were made for young people enrolled in courses that are not offered remotely.

Colombia’s cash transfer programmes in the long run

These programmes have expanded rapidly and substantially in response to the pandemic, meaning that they are currently operating beyond their original scope and purpose. While this ability to respond quickly is considered a great achievement within government, there are currently no plans to maintain the changes beyond the end of the pandemic, particularly as economic crisis is expected to lead to tight budgetary constraints. As a result, many of the families and young people who started receiving payments during the pandemic could be cut off from financial support.

The COVID-19 pandemic has led the Colombian government to go to extra lengths and adopt innovative strategies, as when re-engaging with families and young people previously removed due to non-compliance with conditionalities. These new strategies could help us understand how to reduce barriers experienced by vulnerable families and young people when attempting to access support from CCTs. It remains unclear, however, whether the government will be able to build on these new strategies. Disappointingly, the government is not currently planning to continue its revised policy around the flexibility of conditionalities, for example, even though most beneficiaries have reportedly continued to comply with conditionalities during COVID even though compliance was neither monitored nor rewarded.

As we argue in a recent commentary in Lancet Psychiatry, the pandemic presents a rare opportunity to redesign anti-poverty strategies so that they are informed by relevant evidence on improving children and young people’s mental health and life chances. Without careful planning of any future redesign for Colombia’s cash transfer programmes, many more families and young people will face highly precarious situations around and beyond the end of the pandemic.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• This article was informed by an in-depth interview with Dr Julián Torres, who was until recently director of the Familias en Acción and Jóvenes en Acción programmes; the full interview (in Spanish) is available via Soundcloud

• For questions about the interview or cash transfer programmes in Colombia, please contact Philipp Hessel

• For more information on the CHANCES-6 project from which this blog emerged, please visit the CPEC website or contact Sara Evans-Lacko

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting