Much has been written about the utmost importance of tackling the security problem in Brazil’s favelas, as well as the troubled relations between favela residents and the police. In this post, Erika Robb Larkins complicates this picture by proposing that, in fact, a more pressing urgency is the limited policy attention to healthcare in these communities. She argues that improving accessibility to healthcare services and addressing preventable health problems would require long-term investment and planning, resulting in favelas’ greater buy-in of government policies.

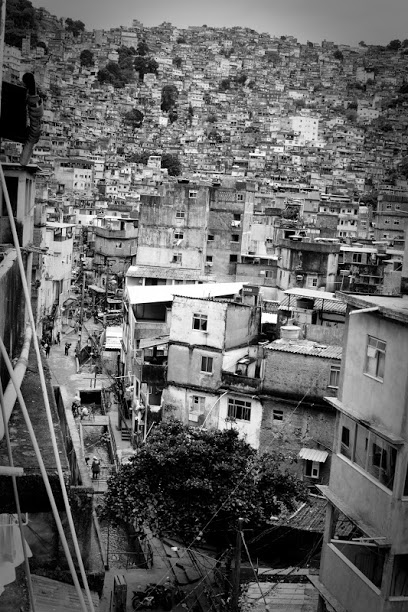

I have been doing research in the Rio de Janeiro community of Rocinha for almost a decade. Living in the favela intermittently over that time, I have heard gunfire fly outside my window, interviewed traffickers, and been searched by police more times that I can count. I have written about violence and security as problems that deeply affect social and cultural life. As time has gone by, however, I have noticed that the majority of people that I know in the favela don’t die from bullets, from offending gun-toting traffickers, or even from police violence. They die from stupid, silly things that make me want to cry: from chronic uncared diabetes and poor diet, from the inability to access emergency medical services in the case of stroke or heart attack or from infectious diseases that simply shouldn’t be — like tuberculosis or leptospirosis (caused by contact with rat urine).

Though I have attempted to avoid addressing medicine and human suffering in my academic work, I have come to see the shortcomings in the public healthcare system as vital elements of the security problem in places like Rocinha. While at first blush addressing the crippled public healthcare system vis-à-vis the lives of favela residents might seem distant from security, I would argue otherwise.

The central favela-based policy currently in effect, “pacificação”, or “peacemaking”, seeks to reclaim territory from the drug traffickers who have long governed local life[i]. It promises increased security and reduced inequality, expanded social projects, and the integration of the favela and its residents into the larger fabric of the city. In Rocinha, however, evidence indicates that pacificação has produced neither security, nor opportunity. As we see in the failures of Iraq and Afghanistan, insecurity and violence cannot be solved with armed force, or with the simple addition of more guns and more “security”. Pacificação is right in that it recognises that security changes can only come as a result of the transformation of the state/favela relationship. But it is wrong in assuming that attempts to reconfigure favela security are the most vital.

Indeed, security, prior to government intervention at least, was not a top priority for Rocinha residents. In my conversations with people over the years, residents identify three basic things that would most improve their lives: healthcare, education and basic sanitation. They believe that they have a right to these services as citizens and that they should be provided by the state. Instead, what they get from the state are substandard services, accompanied by a punitive politics of policing (before and after pacificação, albeit in different forms). The focus is always on security to the exclusion of other core issues. Different tactics are urgently needed.

Brazil’s constitution guarantees healthcare for all citizens. This alone is a major accomplishment. But the public system (Sistema Único de Saúde or SUS) is underfunded and understaffed, especially in urban areas. It fails to adequately care for the country’s poorest residents, who already experience what Vargas and Alves (2010: 613) describe as a highly racialized “relational citizenship” or “non-citizenship”.

Addressing basic healthcare would go much further in winning resident allegiance than increasing police patrols. This would entail redirecting funds that are being invested in strengthening security and policing to projects that address the acute healthcare crisis, as well as investing in preventive medicine.

Policy change should address a citywide deficit in resources and availability of public healthcare, particularly emergency services. As I learned during my fieldwork, if you call an ambulance in Rocinha, like in many other parts of the city, it simply will not come. The emergency room in the nearest public hospital is grossly overcrowded. The walls are literally crumbling, and it is common to see sick people lying on the floor, enduring long waits for treatment. I can recount some of the horrors I have seen first-hand, or those I have heard from others: the pregnant woman covered in blood who was told they didn’t have an obstetrician on duty and that she should find another hospital; the man with gangrene overtaking his legs who came daily to wait in line for a month as the infection spread; the patient who showed me a scar from a supposed appendix removal, which was inexplicably on the wrong side of his body! Even the traffickers I knew had their own private doctor and team of emergency surgeons to avoid potential arrest at the hospital and because they considered the public hospitals to be death-traps.

How are people to take seriously state claims to their inclusion into society as citizens, when they are left to die in such places? Instead of state-of-the-art policing, Rocinha’s 150,000+ residents need a state-of-the-art hospital. Rocinha did receive an urgent care center, Unidade de Pronto Atendimento or UPA, as part of recent PAC (Growth Acceleration Programme) upgrades; however, it lacks adequate supplies and doctors. One resident told me on the day she visited they had run out of painkillers. “I couldn’t even get an aspirin”, she lamented, jokingly playing on the acronym and referring to it as the UPA — the Unidade de Péssimo Atendimento (Unit for Terrible Treatment).

Policy should also entail longer-term solutions, such as addressing diet and the prevalence of lifestyle-related diabetes in the favela. Preventable healthcare issues, which are often themselves linked to poverty and the inability to access affordable nutritious food, could also be developed. This would mean designing new programs and educational initiatives and investing in favela youth for the long haul. It would mean enacting change over generations, not just during electoral cycles. It would mean investing in and expanding community-based healthcare, in culturally appropriate and innovative ways (see, for example, the health-related visual activism of NGO Viramundo).

Though less spectacular than arrests of drug traffickers, intervention in public health is much more likely to produce feelings of state legitimacy. Further, overhauling health-related matters in the favela would support claims to the benefit of government intervention, challenging and complicating images of state violence that currently haunt the favela without a credible counter narrative.

[i] On pacification, see this excellent two volume collection of essays from UFRJ/NECVU: http://www.dilemas.ifcs.ufrj.br/page_65.html and http://www.dilemas.ifcs.ufrj.br/page_64.html

Featured image credit: © Rafaela Cardoso Fotografia.

About the Author

Erika Robb Larkins is Assistant Professor in the Department of International and Area studies at the University of Oklahoma. An anthropologist by training, her work focuses broadly on the study of violence and inequality in urban Brazil. Her book, The Spectacular Favela, explores the connections between the production of spectacular violence in Rio de Janeiro and its commodification and consumption. She is currently working on an ethnography of the private security industry in Rio.

The views expressed on this post belong solely to the author and should not be taken as the opinion of the Favelas@LSE Blog nor of the LSE.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Erika did provide an excellent view about the uneasy daily life experienced by Rocinha residents.

Indeed, her insights can be expanded to other favelas in Rio de Janeiro where I live and take actions through Viramundo (access the English version of our website here http://www.viramundo.org/viramundo/Viramundo_%28English%29.html)

I only would add – with her permission- one more assertion: part of the appaling healthcare state policies is due to the influence of health insurance corporations (native and recently US ones).

They are omnipresent and are eager to sell insurance plans to people who live in the favelas, of course with very low coverage.

In our efforts to promote health and environmental participatory education we often include the denouncement of the above mentioned fact.

Because for us our unified health system, the SUS, should get by and be improved in quality and access to become a real advance for all citizens.