In December last year, the term ‘rolezinho’ circulated in the Brazilian news media. It was used to describe social gatherings of youth in shopping centres across the country. In this post, Inés Alvarez-Gortari reflects on what rolezinhos can tell us about the current state of Brazilian social development in terms of the raise of the ‘new’ working class and the fragmented urbanisation in Brazilian cities.

In December last year, the term ‘rolezinho’ circulated in the Brazilian news media. It was used to describe social gatherings of youth in shopping centres across the country. In this post, Inés Alvarez-Gortari reflects on what rolezinhos can tell us about the current state of Brazilian social development in terms of the raise of the ‘new’ working class and the fragmented urbanisation in Brazilian cities.

In Brazil, the ‘rolezinhos no shopping’ have come to refer to the massive informal social gatherings of youths in shopping centres that took Brazil by surprise last year. The rolezinhos were not a formal, organised movement with an overriding objective, but were rather spontaneous in nature. Yet at the same time they shouldn’t be dismissed as an isolated episode of kids’ play. In the following paragraphs I use the rolezinhos as an interesting window through which to draw new insights on two interlinked phenomena: the rise of Brazil’s new working classes and the fragmented urbanisation experienced by Brazilian cities, as vividly illustrated by Sao Paulo’s case. But allow me to provide some background information first.

The first rolezinho to be known took place in Sao Paulo, in Shopping Metrô Itaquera, in early December 2013 and is estimated to have congregated around 6000 adolescents from the city’s peripheries. The phenomenon spread to other cities, but it is in Sao Paulo where they flourished the most. The rolezinhos caused great controversy. The fact that the teenagers participating in the rolezinhos were mostly black, poor, funk music fans and from urban peripheries fuelled their infamous reputation in the eyes of Brazilian media and upper classes. For the latter, shopping centres were no place for these kids to hang out.

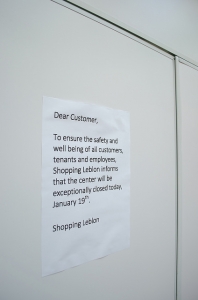

Over the following weekends youths continued to flock in their hundreds and thousands to shopping malls in Sao Paulo’s peripheral areas to socialise, despite the risk of clashes with the Military Police arising out of the latter’s attempt to disperse the youthful and seemingly dangerous crowds. By the end of January 2014 this social phenomenon died down, following restrictive legal measures implemented by shopping malls prohibiting such large scale gatherings. The negative reactions against the rolezinhos revealed the extent to which racism and classism continue to be deep rooted in Brazilian society.

Through the use of social media, the rolezinhos were organised by teenagers in an informal manner in order to simply socialise and flirt among peers. I conducted a small-scale qualitative study (Alvarez-Gortari, 2014) in which my respondents confirmed that such gatherings offered the opportunity to ‘make new friendships’, ‘meet new people’, ‘take pictures’ and ‘meet Facebook friends in person’. They also stated that the shopping malls were chosen as venues since they were seen as spacious enough to host a large crowd.

Brazil’s ‘new working classes’

When I asked my respondents what they usually did in their free time, the most cited answer was that of visiting a shopping mall at the weekend with friends. As observed by Beguoci (2014), the rolezinhos are simply an amplified version, facilitated by social media, of youths’ habitual outings to the shopping malls in the periphery. Moreover luxury goods featured among the items they had bought on such shopping ‘strolls’ with their friends, such as Mizuno sport shoes which cost around R$1000 (around £250).

The rolezinhos are symptomatic of Brazil’s economic development, which has allowed for the prosperity of the lower social classes. Souza (2010) brands them as the ‘new working classes’ as they continue to work in menial jobs characterised by long hours and low pay but who also benefit from the federal government’s social policies enabled by the country’s favourable economic climate. Moreover, in contrast to their grandparents, these new working classes are purchasing goods of individual consumption, such as clothes, phones and electronic gadgets (Caldeira, 2014).

It is estimated that within six years 20 million Brazilians experienced a rise of income from the tier ranging US$430-600 (‘Class D’) to that of US$600-2600 (‘Class C’) (Oliven and Pinheiro-Machado, 2012). The result has been an increase in purchasing power and consumption, also facilitated by the spread of consumer credit as a way of expanding Brazil’s internal market. It is no coincidence that in the past 20 years many shopping malls have opened in the traditionally considered ‘poor’ peripheries of many Brazilian cities, including Sao Paulo (Caldeira, 2014). Indeed the shopping malls came to the periphery, not the other way around. In 2013, Sao Paulo contained 53 shopping centres (and with plans to construct many more), therefore being by far the city with the most malls in Brazil, greatly surpassing the runner-up, Rio, with 37.

Perpetuating Sao Paulo’s urban fragmentation

As Brazil’s largest city with over 20 million inhabitants, Sao Paulo is also a highly segregated and unequal city. In a context of democratisation, privatisation and rising levels of crime, Sao Paulo has iconically become a ‘city of walls’ permeated by a collective fear and abandonment of public space, by both the elites and working classes (Caldeira, 2000).

When the rolezinhos took the everyday practice of socialising to a mass scale, the choice of the habitual shopping malls as venues revealed a lack of alternative open spaces. The consequence of building walls and surveillance systems as a response to fear of crime has led to the fear of public space (Caldeira, 2000), even in the periphery. This means that in Sao Paulo, public space no longer seems to be a site of mixed social diversity and interactions. Even the act of socialising has become restricted to specific spaces and times and in Brazil the shopping mall has become a place associated with this function.

The rolezinhos may have been an ephemeral fad among youngsters but one thing is certain: they signalled that the real issues at the heart of Brazilian society are the persistently deep socio-economic inequalities. As Peter Marcuse reminds us, for there to be truly democratic space, such gross inequalities have to be addressed.

In the meantime, public authorities can begin by implementing a clear policy of investment directed towards recuperating the quality of urban space (Rolnik, 2000), in order to promote the idea of a connected, heterogeneous city that is more democratic than its current fragmented version.

References

Alvarez-Gortari, I. (2014). Rolezinhos: youth culture, urban fragmentation and the search for socialising spaces in São Paulo. Master’s dissertation, Department of Geography and Environment. London School of Economics, UK.

Beguoci, L. (2014). Rolezinho e a desumanização dos pobres. N.p., n.d. Web.14 January 2014.

Caldeira, T.P.R. (2000). City of Walls: Crime, Segregation and Citizenship in Sao Paulo. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Caldeira, T.P.R. (2014). Qual a Novidade dos Rolezinhos? Espaço público, desigualdade e mudança em São Paulo. Novos Estudos 98, pp. 13-20.

Marcuse, P. (2013). Blog #33 – The Five Paradoxes of Public Space, with Proposals. Peter Marcuse’s Blog. N.p., n.d. Web. 12. May 2013.

Oliven, R. G. & Pinheiro-Machado, R. (2012). From ‘Country of the Future’ to Emergent Country: Popular Consumption in Brazil. iN Pertierra, A. and Sinclair, J. (eds) Consumer Culture in Latin America (pp. 53 – 65), New York, Palgrave Macmillan.

Rolnik, R. (2000). O lazer humaniza o espaço urbano. In SESC SP. (Org.) Lazer numa sociedade globalizada. São Paulo: SESC São Paulo/World Leisure.

Souza, J. (2010). Os Batalhadores Brasileiros: Nova Classe Média ou Nova Classe Trabalhadora? Belo Horizonte: Editora UFMG.

About the Author

Inés Alvarez-Gortari holds a BA in Geography and MSc in Urbanisation and Development from the LSE. She is deeply interested in issues relating to youth, development, education and urban peripheries. She is currently working with educational projects and as a fundraiser at ONG Mundo Novo – a grassroots NGO situated in Chatuba (Mesquita), which lies on the outskirts of Rio de Janeiro’s metropolitan area.

The views expressed on this post belong solely to the author and should not be taken as the opinion of the Favelas@LSE Blog nor of the LSE.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.