Since the death of Hugo Chávez last year, the economic, political and social vision of Venezuela has been uncertain. In this post, Mireya Lozada discusses the current state of fragmentation in the Venezuelan society, as well as the psychosocial impact of polarisation on large social sectors in the country and on the ruling government and its opposition. She also presents the challenges this situation entails for psychologists and social researchers working on the ground, and potential avenues to address them.

Since the death of Hugo Chávez last year, the economic, political and social vision of Venezuela has been uncertain. In this post, Mireya Lozada discusses the current state of fragmentation in the Venezuelan society, as well as the psychosocial impact of polarisation on large social sectors in the country and on the ruling government and its opposition. She also presents the challenges this situation entails for psychologists and social researchers working on the ground, and potential avenues to address them.

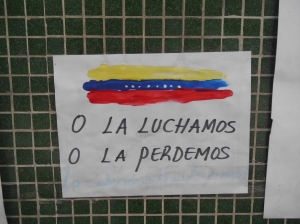

Quiet, from one side to another of the Caracas’s Metro, students protest against violence, insecurity, scarcity and corruption by showing banners:

“Love to our Venezuela is bigger than our differences. Join the fight!”

“We are not criminals. [Say] No to violence”.

Above the road, on the border of the hill, is Catia, one of the poorest and most populated neighbourhoods of the city, where a community leader exhorts:

“Motherland is me, motherland were my ancestors, motherland are my children and motherland will be my grandchildren and the children of my grandchildren. Thus, what do we want as motherland? A motherland that embraces each and every one of Venezuelans, without exception. Simply, we are [Venezuelans], not the way we are now talking about a group that is Chavista and a group that is the opposition. No, I want the wave that comes in this river to become a single line, to become a single waterfall, like Salto Ángel*. All of us to be, to arrive together to an end and to fall in that river, that’s what I want as motherland. I like to think that we Venezuelans can move forward hand in hand, standing shoulder to shoulder, chest swollen [with pride] and all looking there. To sit on the road, look ahead and ignore the path you already walked, to acknowledge that you made mistakes but that from now on you can do things better”.

Women and young people, perhaps the groups most affected by the impact of polarisation and violence, cry out for the end of confrontation, for justice and inclusion. They struggle for the future and believe in a country that guarantees pacific and democratic coexistence of its inhabitants.

It is polarisation that occupies private and public spaces, which has divided cities, regions and states in sectors, ghettos and territories for and against the government. It has also left material and symbolic scars in family, school and community spaces, generating a strong individual and collective impact, especially amongst popular sectors.

Polarisation shatters the social fabric. It legitimates and naturalises violence, and makes invisible the historical and complex structural causality of the socio-political conflicts (e.g. exclusion, poverty, unemployment, corruption and exhaustion of the political model). Thus, this conflict only denotes the confrontation between the clashing actors and political parties, thereby excluding the remaining social sectors in seeking solutions to their problems (one of which is the impact of polarisation). However, the latter sectors, and particularly those in poorer neighbourhoods, are used instrumentally during political and electoral processes to serve the confrontation between government and opposition.

In summary, social polarisation, which seems to erect itself worldwide and extend as a socio-political mechanism of control and power, manifests itself with its own characteristics in the Venezuelan context. In doing so, this process produces important challenges to the experience of participatory action research that the Central University of Venezuela puts forward.

Across 14 years of socio-political conflict, a number of programmes (conflict mediation, psychosocial attention to families, schools, communities, groups, and institutions) have evinced the psychosocial impact generated by polarisation. This evidence allows us to psychologically characterise this process, which is suffered by wide sectors of the Venezuelan population:

- Narrowing of the perceptual field. Unfavourable and stereotyped perception of the opposite group generates a dichotomous and excluding vision: “us and them”.

- A strong emotional charge. Acceptance and rejection, without caveats, of the opposite person or group.

- Personal involvement. Any fact affects the individual.

- Shattering of common sense. Dialogue and debate between diverse perspectives are supplanted with rigid and intolerant positions.

- Perception of solidarity and cohesion inside one’s own group and latent or manifest conflict between opposite groups.

- Families, schools, churches, communities and other social spaces are positioned on any of the two conflicting sides.

- People, groups and institutions hold the same attitudes of exclusion, rigidity and clash that characterise the political struggle.

With these expressions, alongside growing impunity, violation of human rights and the perception that civic manifestation is useless, the possibility of having multiple perspectives is closed down. In a context of threats, aggression, negation and rejection of the opponent, distrust in the government system increases, as does despair about pacific avenues for conflict resolution.

Our country, our universities and our training programmes are now facing their biggest ethical and political challenge: to construct citizenship and democratise conviviality. This is a long and hard job of citizen education that would allow developing collective actions seeking to contextualise the conflict in a socio-historical perspective. This challenge also includes the transformations of representations of oneself and others, the construction of new, non-polarised media metaphors and discourses, as well as the recognition of social imaginaries and shared symbolic universes. Finally, the task would include addressing the psychosocial impact of the conflict through social restoration.

These are times of taking on the historical challenge of politics understood as everyday life; these are times to create and signify the imaginary of the ‘we’, with meaning and direction around a common future.

*El Salto Ángel, is the highest cascade of the world (979 metres high), located in the Canaima National Park, Bolívar State, Venezuela.

All photographs courtesy of Mireya Lozada.

To know more about these and other issues, the author recommends the following links (in Spanish):

Lozada, M. (Ed., 2006). El derecho a la paz. Voces de niñas, niños y adolescentes en Venezuela. Caracas: UCV-Cecodap.

Lozada, M. (2008). ¿Nosotros o ellos? Representaciones sociales, polarización y espacio público en Venezuela. Cuadernos del Cendes, 25(69), 89-105.

Centro Gumilla Foundation

Network of psychological support, Central University of Venezuela

About the Author

Professor Mireya Lozada Santelis is a doctor in psychology (Université de Tolouse-Le Mirail, France) and former director of the Institute of Psychology at Central University of Venezuela (2009-2013), where she currently serves as the Coordinator of the Political Psychology Unit and of the Masters in Social Psychology.

The views expressed on this post belong solely to the author and should not be taken as the opinion of the Favelas@LSE Blog nor of the LSE.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.