Britain, like other countries, has seen overwhelming public support for ‘hard’ policy measures during the pandemic. This runs counter to previous evidence that people prefer ‘soft’ interventions, such as nudges. Is this shift permanent? Could it apply to climate policy as well as the pandemic? Sanchayan Banerjee (LSE), Manu Savani (Brunel University London) and Ganga Shreedhar (LSE) look at the evidence so far.

It has been almost 15 months since the UK government introduced the first national lockdown to contain the spread of COVID. Two more have followed, including restrictions such as border controls and travel bans. The British government has now delayed the easing of the remaining lockdown measures until 19 July.

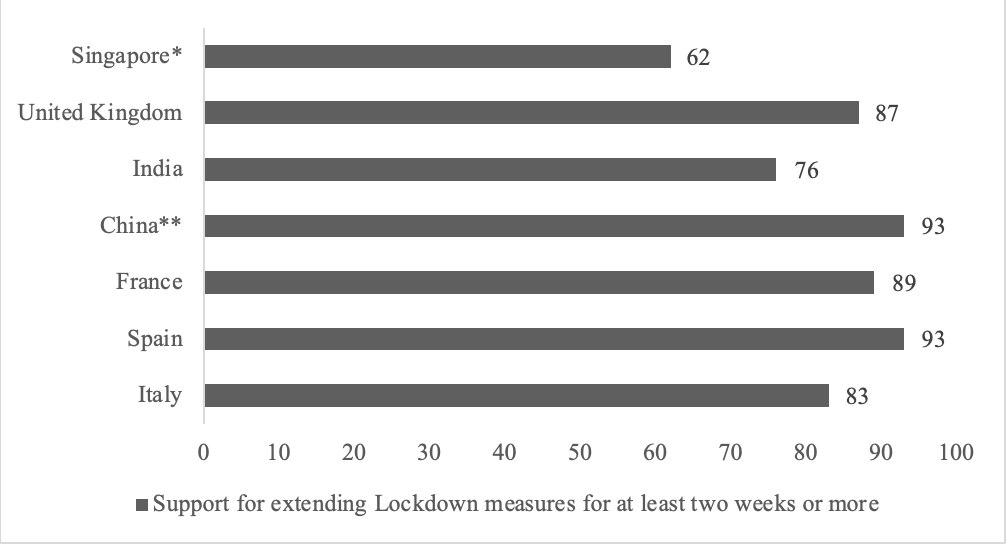

Given emerging evidence about the growing popularity of nudges amongst both the public and policymakers, it was a surprise to some that 93 percent of people favoured these ‘hard’ public policies to begin with – and the situation did not change much over time (see Figure 1). Public support for these measures has remained consistently high. In a recent survey poll by YouGov of more than 3,500 British respondents, over 70 percent of the sample has favoured postponing the original easing of lockdown on 21 June. Support for the delay increases in older age groups. This kind of public support for harder policy measures is not limited to the UK: many other countries have implemented hard public policies in response to the virus and recorded high public support for them.

Figure 1: Public support for harder measures

Notes: *Support for imposing self-quarantine measures; **Support for self-quarantine measures. Authors’ calculations drawing on data from Bhatia (2020) for India, Freitas (2020) for United Kingdom, Redfield & Wilton Strategies (2020) for France, Spain and Italy, Infogram (2020) for Singapore and Ipsos (2020) for China. Source: Banerjee et al., (2021).

Strong public support for harder policy measures – like those that restrict choice, mandate action, or change monetary incentives through fines – runs counter to prior evidence that pointed towards significant support for ‘soft’ public policies. These include persuasive and information-based approaches, including nudges. So what explains this apparent puzzle in public policy preferences? Is it a radical shift, where harder measures are becoming increasingly popular? Or is this a temporary preference reversal, triggered by the unique circumstances of the pandemic? To investigate further, we ask the broader question of what determines public support for ‘soft’ versus ‘hard’ public policies (see full paper here).

We reviewed a series of articles from disciplines including public policy and political science, psychology, behavioural economics, including empirical papers that were largely focused largely on health and pro-environmental behaviours. A range of methods have been used to investigate policy preferences, including experimental, observational, and qualitative methods. A descriptive analysis of these papers and their findings are summarised in our paper. We defined ‘hard’ policy instruments as those that restrict choice through laws, regulations and mandates and can alter financial incentives through levies, taxes and subsidies. Soft policies included ‘moral suasion’ and educational campaigns, such as ‘fact-based’ health warnings, which focus on providing information to alter behaviours.

A number of factors play a role in determining public support for different policy instruments. At an individual level, preferences are determined by self-interest, a person’s prior experience with the policy issue, and perceived effectiveness of different instruments. There is mixed and inconclusive evidence to suggest age, education and gender matter. Political ideology does appear to play a role in policy preferences, with left-leaning individuals more likely to support hard interventions for the climate and policies addressing obesity.

Studies also highlight that preferences are context-specific: the messaging, and framing matter, as do the policy instruments on the table. For example, people may be less likely to choose a carbon tax if a nudge is presented as an alternative. While empirical evidence suggests some country-level differences, the underlying mechanisms to explain this (is it political culture? Is it political trust?) are less well developed.

An important and timely question is whether increasing support for harder public health measures might spill over into higher acceptability of harder environmental regulation, like a meat tax or a carbon price. We find little and mixed evidence on the directions of the policy spillovers, meaning there are no easy answers to this question.

We conclude that we have a relatively limited understanding about how the public ranks and chooses between different types of softer and harder policy instruments. Here are some of our suggestions for future research.

- We can improve our evidence base with more robust and comparable metrics for policy preferences, using well tested techniques like stated preference valuation methods to uncover both policy preferences as well as what policy attributes matter to people.

- Surveys and experimental studies that are repeated over time can help understand the stability of preferences as well as change (and perhaps preference reversals), and to investigate the mechanisms explaining stasis (political culture and trust) or change (spillover effects and personal experiences).

- We should also look to enrich theory with explanatory factors such as behavioural biases (present bias, loss aversion, status quo bias), emotions (fear, anger, hope) and personality traits (fatalism, risk aversion) to better understand variation across individuals.

As our recommendations show, the need for multi-disciplinary research has never been greater.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

1 Comments