During the COVID-19 pandemic, governors, attorneys general, and public health officials have scrambled to enforce social-distancing guidelines and mask wearing. Their efforts were opposed in several states by those who argue that mandatory face-coverings are unconstitutional. Efforts to enforce mask wearing have been complicated by legacy anti-mask legislation in almost 40 percent of states (and the District of Columbia), which was passed in the 19th– and 20th-centuries in response to organizations like the KKK. Shyam K. Sriram, Will Gigerich, Meet Patel and Kayla Miller discuss the origins, evolution and current impact of anti-mask legislation in the United States.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, governors, attorneys general, and public health officials have scrambled to enforce social-distancing guidelines and mask wearing. Their efforts were opposed in several states by those who argue that mandatory face-coverings are unconstitutional. Efforts to enforce mask wearing have been complicated by legacy anti-mask legislation in almost 40 percent of states (and the District of Columbia), which was passed in the 19th– and 20th-centuries in response to organizations like the KKK. Shyam K. Sriram, Will Gigerich, Meet Patel and Kayla Miller discuss the origins, evolution and current impact of anti-mask legislation in the United States.

On July 15th, 2020, Brian Kemp, the Governor of Georgia, issued Executive Order No. 03.14.20.01, which declared “a Public Health State of Emergency in Georgia.” Buried about three-fourths of the way through the order was this statement: “any state, county, or municipal law, order, ordinance, rule, or regulation that requires persons to wear face coverings, masks, face shields, or any other Personal Protective Equipment while in places of public accommodation or on public property are suspended to the extent that they are more restrictive than this Executive Order.” Three days later, Governor Kemp sued the Mayor of Atlanta, Keisha Lance Bottoms, arguing that Bottoms’ own executive order – which requires mask wearing in outside or indoor commercial settings – was more restrictive than the governor’s and that her administration must comply with state law.

The state politics of mask mandates

To an outsider, this might seem like the kind of gubernatorial power grab that is common in American politics, but this tussle highlights the significant, yet poorly understood, history of masking laws in the United States. What many simply do not know is that Georgia was already one of 18 states with an anti-masking law on its books. In the COVID-19 era, the debate has shifted remarkably from laws against masking to laws in favor of mandatory mask wearing. The other issue that has bubbled to the surface over the last year and a half is a question of federalism and the devolution of powers from state legislatures to local (city and county-level governments).

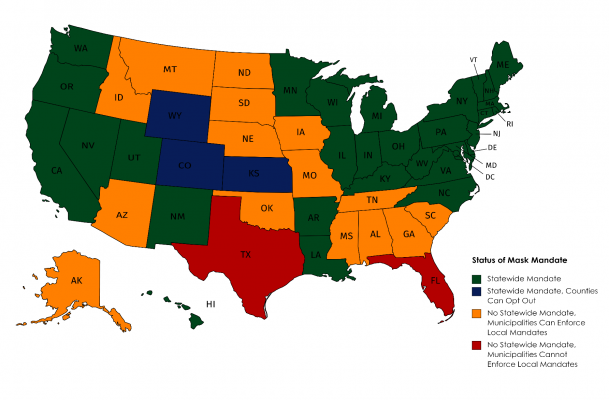

We found no fewer than four types of COVID-19 related mask mandates across the US (see Figure 1). While 30 states have mandatory mask mandates, three additional states allow counties to opt out by choice (only Wyoming, Kansas, and Colorado). On the other side are 15 states which have no statewide mask mandates, but municipalities have the power of devolution i.e., mask mandates can be enforced at the local level. Only two states, Florida and Texas, have no statewide mask mandate and do not allow municipalities to opt out or make their own decisions.

Figure 1- State Mask Mandates

The history of anti-masking laws in the US

The first anti-masking laws originated in New York in 1845 in response to a violent uprising of tenant farmers who disguised themselves in order to attack police officers. Between the 1920s and 1950s, over a dozen US states passed “anti-mask” legislation in response to the Ku Klux Klan (KKK), with several states later becoming embroiled in civil liberties battles over the right to wear masks and hoods. In 1999,the Southern Poverty Law Center commented on this irony; writing that the very laws created to “protect the public from Klan intimidation and violence” were being challenged by the KKK as restrictive of its members’ claim to anonymity. While the US District Court for Northern Indiana found in favor of the KKK in American Knights of the Ku Klux Klan v Goshen, Indiana (1999) with regards to a 1998 anti-masking law, in 2004 the US Second Circuit Court of Appeals ruled against the KKK’s claim that New York’s anti-mask law was an attack on the freedom of association.

Photo by Zachary Keimig on Unsplash

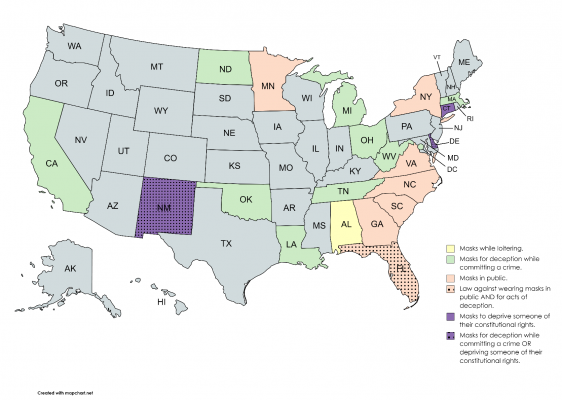

While many states (and the District of Columbia) have anti-mask statutes, their scope varies tremendously (see Figure 2). Alabama’s law is narrowly tailored to loitering, whereas Connecticut’s is specific to Klan-like costuming and references “burning a cross.” Approximately 50 percent broadly ban face coverings in public, while the other half only ban face coverings while in the commission of a crime. It is also important to note that several states ban masks while possessing a firearm. In a recent California Law Review article Caroline V. Lawrence of Yale Law School and colleagues, noted that despite the differing origins of these laws, “most anti-mask laws share some characteristics. For instance, most statutes include a requirement that the violation must take place in public … Some simply state masks must not be worn “in public” or “on public lands … Some require a number of people, such as two or more … Some specify who these people must (not) be, such as by incorporating age requirements … or sex offender status.”

Figure 2 – The Scope of Anti-Masking Laws

Anti-masking laws and 21st century protest movements

Legacy masking laws occasionally become relevant in the United States in response to a specific type of protest or event. For example, in 2011, there was a flurry of renewed interest in masking laws related to the Occupy Wall Street movement. The New York City Police Department arrested demonstrators during the Occupy Wall Street protests for “‘loitering and wearing [a] mask.’” The following year, several people were arrested in New York while publicly wearing masks to show their disapproval for the treatment of Russian punk band Pussy Riot. In 2013, a Florida police officer was arrested for wearing a “V for Vendetta” mask during a protest against the Affordable Care Act, a rare enforcement of a 1951 anti-masking measure.

When white nationalist Richard Spencer, gave a speech at Auburn University in 2017, campus police officers demanded that counter-protestors remove their face coverings to comply with Alabama state law. In the same year, three students from Virginia Commonwealth University were arrested by the Richmond Police Department for “wearing a mask to conceal their identity” while attending a tense protest over a statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee. Those charges were later downgraded for all three students. In 2019, a protest organizer in Hoover City, Alabama was arrested for wearing a mask while protesting a police-action shooting.

In states that do not have anti-masking legislation, some legislators have advocated the enactment of such legislation. In 2017, an Arizona Republican state representative advocated for anti-masking laws after peaceful protests turned violent during a Trump rally in Phoenix; the representative even went as far as to compare the anti-Trump protestors and the Black Lives Matter members to the Ku Klux Klan. The state of New York repealed the anti-masking clause in the state’s loitering statute on June 13, 2020. Around the same time, the City Council of the District of Columbia passed a resolution to repeal their anti-masking law.

Legacy anti-mask laws and push back against COVID-19 mask mandates

During the COVID-19 pandemic some politicians have expressed concern over requiring citizens to wear face masks in public. Governor Greg Abbott of Texas originally preempted any local regulations that would impose fines for individuals who did not wear a face mask. However, after a backlash from local government officials and residents, the governor reversed his decision and ordered all citizens in counties with more than twenty COVID-19 cases to wear a face mask in public. In June 2020, Nebraska Governor Pete Ricketts took a different approach. He stated that local governments that implemented mask rules would not receive any federal coronavirus-relief funding.

Anti-masking laws in some states have transitioned from protecting against the Ku Klux Klan to protecting those who put our communities in danger by refusing to wear a face covering during the COVID-19 pandemic. In July 2020, in North Carolina, Republican state legislators blocked a bill to halt the enforcement of the state’s anti-masking law in an attempt to invalidate the Democratic governor’s mask mandate. However, a few days later, the legislature agreed to suspend the anti-masking law indefinitely. In 2020, Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida issued an executive order which, while still allowing local governments to issue mask mandates, prevents local governments from enforcing their mandates through fines and penalties. By March 2021, Governor Abbott of Texas lifted the state’s mask mandate and opened all businesses to 100 percent occupancy; the order also prevents local governments from enforcing their own mandates.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3wcen7x

About the authors

Shyam K. Sriram – Gonzaga University

Shyam K. Sriram – Gonzaga University

Shyam K. Sriram, Ph.D., is a lecturer in the Department of Political Science at Gonzaga University.

Will Gigerich – Butler University

Will Gigerich is an undergraduate student at Butler University.

Meet Patel – Butler University

Meet Patel is an undergraduate student at Butler University.

Kayla Miller – Butler University

Kayla Miller is an undergraduate student at Butler University.