Since the 1970s, major US defense contractors have become less innovative than their non-defense counterparts. In new research, Sabrina T. Howell, Jason Rathje, John Van Reenen and Jun Wong assess the US Air Force’s recent ‘Open’ bottom-up reform which gives defense contractors more freedom to go beyond technology specifications. They find that winning Open contracts meant firms were more likely to receive venture capital funding and win patents.

Since the 1970s, major US defense contractors have become less innovative than their non-defense counterparts. In new research, Sabrina T. Howell, Jason Rathje, John Van Reenen and Jun Wong assess the US Air Force’s recent ‘Open’ bottom-up reform which gives defense contractors more freedom to go beyond technology specifications. They find that winning Open contracts meant firms were more likely to receive venture capital funding and win patents.

Military necessity has been the mother of innovation since antiquity. During the Roman attack on Syracuse in 214 BC, Archimedes created several innovations that successfully defended the city including his famous “Claw” – a gigantic crane that dragged enemy ships out of the sea. More recently, Pentagon funding has helped develop jet engines, cryptography, nuclear power, and the Internet. Despite being lauded by policymakers all over the world, US defense R&D seems to have lost its luster in recent decades.

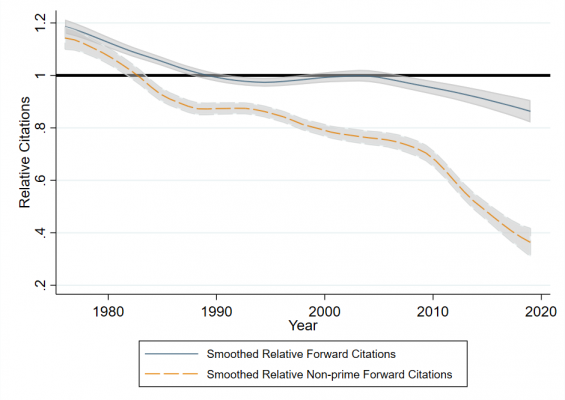

Figure 1 shows that in 1976, the major American defense contractors (“Primes”) produced 15 percent more innovations (as measured by future citation weighted patents) than similar non-defense firms. By 2019, they appeared between 15 percent (if their self-citations were included) and 40 percent (if we drop self-citation) less innovative. This fall is due to both a relative decline in the number of patents granted to primes (despite no loss of market share) and the degree to which other firms see them as useful.

Figure 1 – Innovation by Prime Defense Contractors was stronger than non-defense firms in the late 1970s, but has been in long-term decline

Notes: This Figure describes patent quality for the six major prime defense contractors in 2019 (Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Raytheon/UTC; Harris/L3; Northrop-Grumman, General Dynamics) and all their acquisitions since 1976. We show the number of patents weighted by the number of future citations in the solid blue line and drop “self-citations” to these primes in the dashed orange line. Both lines are expressed relative to the average in the same technology class-year. The dashed line (i) excludes self-citations and (ii) excludes any citations from prime defense contractors and their acquisitions. The measures are smoothed using kernel-weighted polynomial regressions. The gray band around the relative citations represents the 95 percent confidence interval.

Source: USPTO via Howell, Rathje, Van Reenen and Wong (2021)

Senior US defense policymakers have recognized this problem, and see it stemming from both a failure to engage many of the new software-based start-ups and a consolidation among the defense contractors. For example, a tasking memo from the 2019 Under Secretary of Defense tasking memo stated, “The defense industrial base is showing signs of age. The swift emergence of information-based technologies as decisive enablers of advanced military capabilities are largely developed and produced outside of the technologically isolated defense industrial base”.

The Open Reform

To address the problem of declining innovation, the US Air Force (USAF) experimented with reforming their Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) program, which exists at all federal agencies that conduct extramural R&D but has some degree of flexibility in contracting procedures. The “Conventional” approach has been to run SBIR competitions that narrowly specify the technology to be procured. In 2018 and afterwards, USAF made some competitions “Open Topics” which gave applicants much more freedom to suggest projects which the firms thought would have potential military benefits.

Working with the USAF, we obtained the details on applications and winners of both Conventional and Open topics between 2003 and 2019. We found that that the type of firms who applied for Open were very different from those who applied for the Conventional programs. They were half as old, half as likely to have previously applied for an SBIR program, more likely to be in software than hardware, and more likely to be located in high tech hubs. In short, Open attracted many more “new entrants”, just as the reformers wanted.

But did the reform improve outcomes? Senior administrators at the USAF have been concerned that SBIR projects rarely translate to “programs of record” – a technology embodied in a non-SBIR Department of Defense contract. They also care about whether the winners obtain outside funding from Venture Capital (VC) to help develop dual-use technologies for non-military use.

Three evaluators score each SBIR application and the combined score determines whether an applicant is funded or not. We use this information to compare firms who just lost versus those who just won in a “Regression Discontinuity Design”.

“190411-F-OD616-0005” (CC BY-NC 2.0) by Official U.S. Air Force

We find that there is a big jump in the probability of getting future VC funding for firms just above the threshold for Open competitions, compared with those who were just below. By contrast, there is no jump for winners of the Conventional program. Similarly, Open competitions seem to have a positive causal impact on getting a future non-SBIR military contract, whereas there are no effects for Conventional awards.

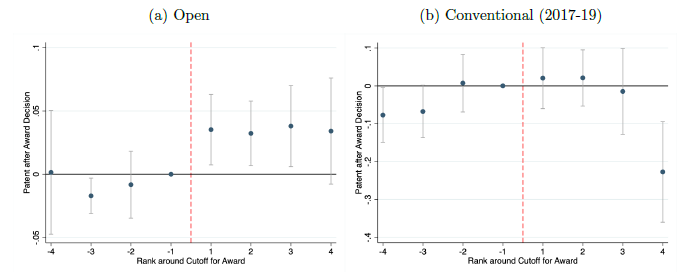

We also found positive causal impacts of winning Open awards on patenting – especially more original innovations – but no effects from Conventional (see Figure 2). In fact, the main effect of winning a Conventional program seemed to be to increase the chances of winning another Conventional competition in the future, creating a kind of “lock-in” effect for incumbents.

Figure 2 – Winning an Open Competition means a higher probability of future innovation (but winning a Conventional Competition Does Not)

Notes: These figures show the probability that an applicant firm had any ultimately granted patent applications within 24 months after the award decision. In both panels, the horizontal axis shows the applicant’s rank around the cutoff for an award. A rank of one indicates that the applicant had the lowest score among winners, while a rank of -1 indicates that the applicant had the highest score among losers. We plot the points and 95 percent confidence intervals from a regression of the outcome on a full complement of dummy variables representing each rank, as well as fixed effects for the topic. The omitted group is rank=-1.We include first applications from 2017-19.

There were two reasons for the success of Open topics. First, new entrants appeared to have bigger effects on VC, though not on the other outcomes we study. A second reason is the bottom-up nature of innovation in Open, which appears to be relevant beyond selection. We provide evidence of this in two ways. In one analysis, we show that other reforms at the same time as Open which also attracted new entrants but were not bottom-up did not have positive causal effects on our success measures. In the second analysis, we find that among Conventional competitions, winning an award among those that were relatively more open-ended (using machine-learning techniques to measure the variation of text applicants made within each topic competition) did have a positive causal effects on innovation, just like the Open competitions.

The benefits of bottom-up innovation

Bottom-up innovation has recently been encouraged by many governments and private sector firms around the world. Our findings suggest that a reform encouraging this type of innovation procurement at the U.S. Air Force was successful. Our findings do not mean there is no role for Conventional top-down approaches in the Department of Defense or elsewhere, as there may be other benefits that we cannot measure. However, they do suggest there should be an ongoing role for Open both in the military and perhaps more widely in the private sector.

- A version of this article first appeared at VoxEU and is based on POID Working Paper No. 4, “Opening up Military Innovation: An Evaluation of Reforms to the U.S. Air Force SBIR Program”

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3vWkZYj

About the authors

Sabrina T. Howell – NYU Stern

Sabrina T. Howell – NYU Stern

Sabrina Howell is an Assistant Professor of Finance at the New York University Stern School of Business. She is also a Faculty Research Fellow at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

Jason Rathje – AFVentures

Jason Rathje – AFVentures

Jason Rathje is a graduate of the Stanford Technology Ventures Program and currently serves as the Director of AFVentures. His research focuses on the overlap of government funding, entrepreneurship, and technical innovation, with special attention on how firms form research and development relationships with government agencies.

John Van Reenen – LSE Economics

John Van Reenen – LSE Economics

John Van Reenen is the Ronald Coase Chair in Economics and School Professor, Department of Economics at the LSE. He was also the director of Centre for Economic Performance (2003-16), at LSE before moving to MIT.

Jun Wong – NYU Stern

Jun Wong – NYU Stern

Jun Wong is a research assistant at NYU Stern and an incoming economics phd student at University of Chicago. Before this, he was a research data analyst at the department of Environmental Science, Policy, and Management at UC Berkeley and earned a BA in Economics from Berkeley.