Joe Biden’s America Rescue Plan Act was recently passed by Congress, but without the provision to raise the federal minimum wage to $15. Jeannette Wicks-Lim argues that the politics around increasing the federal minimum wage provide a near-perfect microcosm of wider US politics, including a clear articulation of the country’s social hierarchy. She reminds us that current minimum wage policies, including the tip-credit, disproportionately affect women, and especially Black women. Despite a majority of voters supporting raising the federal minimum, she writes, partisanship and lobbying means that Congressional action is unlikely.

Joe Biden’s America Rescue Plan Act was recently passed by Congress, but without the provision to raise the federal minimum wage to $15. Jeannette Wicks-Lim argues that the politics around increasing the federal minimum wage provide a near-perfect microcosm of wider US politics, including a clear articulation of the country’s social hierarchy. She reminds us that current minimum wage policies, including the tip-credit, disproportionately affect women, and especially Black women. Despite a majority of voters supporting raising the federal minimum, she writes, partisanship and lobbying means that Congressional action is unlikely.

Underlying Political Fundamentals

US economic policy turns largely on the machinations of political power, and less on economic sensibilities.

The failure to raise the current $7.25 federal minimum wage to $15 as part of the America Rescue Plan Act of 2021 (ARP) continues the longest stretch of time between federal minimum wage hikes since its inception in 1938. Prior to this 12-year stretch the federal minimum wage had periods of zero increases between 1981 and 1990 (9 years) and 1997-2007 (10 years).

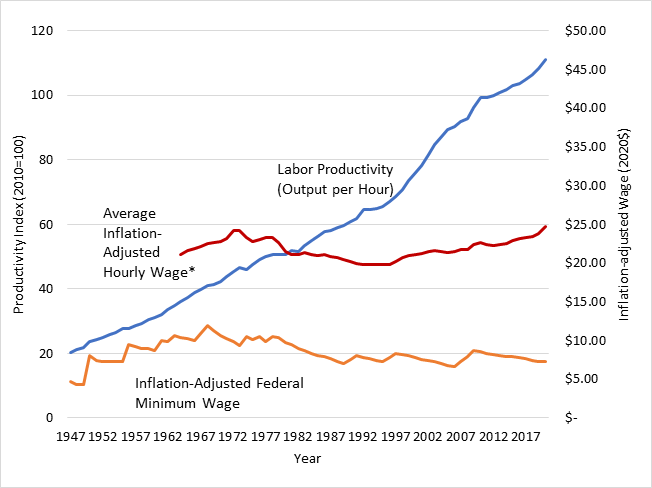

Waning bargaining power of US workers explains these lengthening dry spells, not economic fundamentals. When a large share of the US workers belonged to unions – an explicit measure of their bargaining power – the federal minimum wage kept pace with worker productivity. For example, from the end of World War II until 1968 – when more than one in four workers belonged to a union – the inflation-adjusted federal minimum and worker productivity (output per hour) roughly doubled (see Figure 1). As union membership declined in the 1970s, the federal minimum split off from worker productivity and kept pace only with inflation. So too did average wages. Starting in 1981, the federal minimum wage began a nine-year slide. This is the same year as “the strike that busted unions”—the air traffic controllers’ strike that the Reagan administration famously crushed. Union decline accelerated and the federal minimum wage has since never regained its real value. Worker productivity has more than doubled since 1950, while the inflation-adjusted value of the federal minimum wage has fallen.

Figure 1 – Trends in Inflation-Adjusted Wages and Worker Productivity, 1947-2020

Source: US Department of Labor.

Note: Wages adjusted for inflation using the CPI-U. *Data on average inflation-adjusted hourly wage of production and non-supervisory workers are not available prior to 1964.

At the same time, economic studies find repeatedly that employers do not respond to minimum wage hikes with significant job cuts – the main economic argument against strengthening the minimum wage. Instead, researchers have identified alternative ways that employers adjust to wage hikes, and alternative theoretical models that explain why increases in the minimum wage do not lead to job cuts.

Separate and Unequal

Carve-outs from federal minimum wage coverage outline the race- and gender-based hierarchy of political power in the US. For example, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA) that established the federal minimum, explicitly excluded from equal protection industries that employed high shares of Black workers, and, in particular, Black women such as private domestic service and agriculture workers. According to 1940 US Census data, 70 percent of employed Black women (25-54 years old) held exactly those types of jobs compared to 9 percent of employed white women. The civil rights movement succeeded in eliminating major carve outs through the 1966 FLSA amendments. These amendments extended new protections to nearly one-third of Black workers and explains more than 20 percent of the reduction in racial wage inequality occurring between 1967 and 1980.

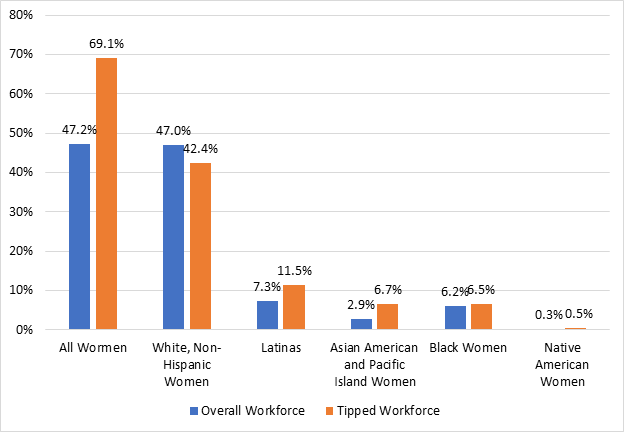

Another carve-out, the tip-credit, continues to leave women, and particularly women of color, unequally protected by the FLSA. The tip-credit allows employers to use the tips workers receive to make up the gap between a sub-minimum $2.13 rate and the full $7.25 minimum wage (or the state minimum rate if it is higher). Women make up 69 percent of workers in tipped occupations such as waitresses, bartenders and hairdressers, compared to their 47 percent share of the overall workforce, with non-white women over-represented (see Figure 2). This sub-minimum rate has lost 47 percent in its inflation-adjusted value since it was last raised in 1991. Legally, employers are supposed to top-off tipped workers’ earnings if they fall short of the full minimum wage rate. Employer disregard for this requirement – i.e., wage theft – is common. The tipping system subjects workers to unstable earnings as well as the whims of their customers – including sexual harassment, bullying, and discrimination. These abuses are predictable, given the tipping convention’s Jim Crow origins. Had the minimum wage measures included in the House’s version of the ARP survived, the tip credit would have been phased out.

Figure 2 – Women in the Overall and Tipped Workforces by Race/Ethnicity

Source: Figure reproduced from National Women’s Law Centre factsheet.

Populist vs. “Under the Dome” strategies

The minimum wage’s extreme popularity among voters is matched by extreme partisanship among legislators, demonstrating the strength of money influence in US’ politics. State ballot initiatives that enable voters to weigh in directly on their state-level minimum wage have raised minimum wage rates above the federal level in 17 states, typically registering voter approval rates of more than 60 percent. In 2019, two-thirds of the US public expressed support for a federal $15 minimum wage.

“Fight for 15 Rally Chicago Illinois 8-22-19_2268” by Charles Edward Miller is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0.

Despite this popularity, lobbying efforts of organizations like the National Federation of Independent Businesses, the US Chamber of Commerce, and the National Restaurant Association, all known for opposing minimum wage provisions, appear to have succeeded so far in an “under-the-dome” strategy (i.e., the dome of the US Capitol building). More than three-quarters of these organizations’ contributions go to Republicans. Partisan voting mirrors this partisan funding: 97 percent (228 out of 235) of House Democrats voted in favor of the 2019 Raise the Wage Act of 2019 and 98 percent (192 out of 197) of the Republicans voted against. With the filibuster still in play, the final hurdle for a federal minimum wage hike appears unsurmountable: a super-majority in a US Senate now evenly split between Democrats and Republicans.

And, the Southern Strategy

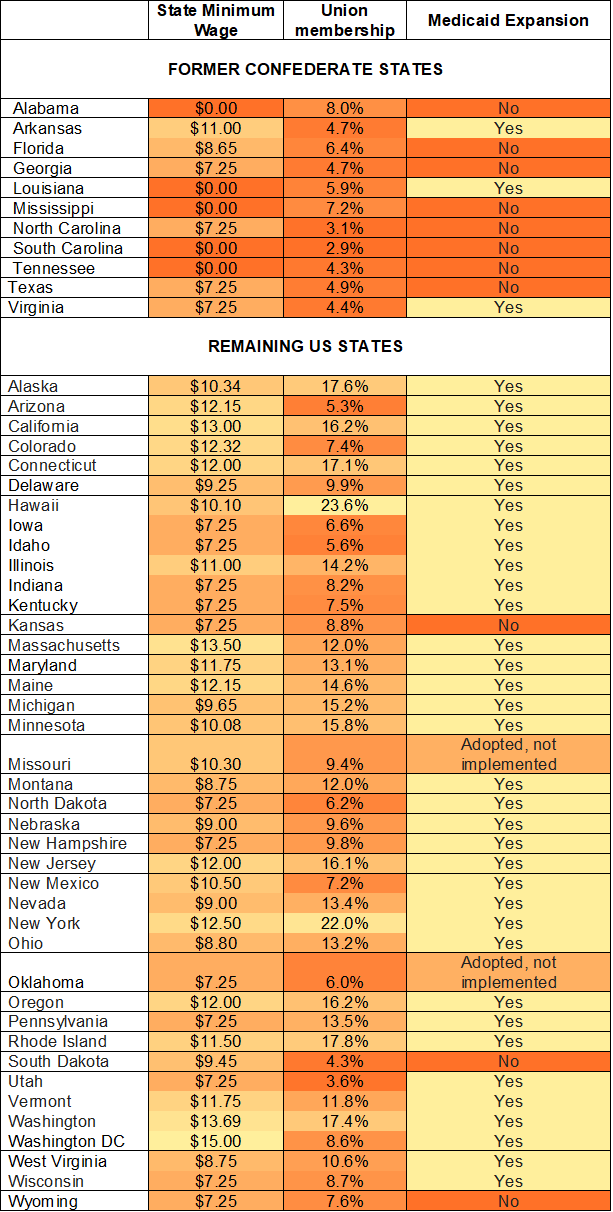

The limited success of minimum wage hikes to state-level action has left behind the majority of Black adults who reside in the 21 states that operate with only a $7.25 minimum wage rate. This is, in part, the lasting legacy of slavery in the South. The fact that 51 percent of non-Hispanic Black American adults currently reside in the ten states that made up the former Confederacy (as compared to 37 percent of all US adults) can be traced to this legacy. This legacy is also discernible in these states’ economic development strategies that rely on a class of working poor, offering among the weakest social and labor protections, including with regard to the minimum wage, union membership, and expansion of Medicaid eligibility through Obamacare—the US’ primary health insurance program for low-income Americans (see Table 1).

Table 1 – State minimum wage, union membership, and Medicaid expansion status by State

Darker shade=Weaker Protections

Sources: State minimum wage rates, union membership, Medicaid expansion status.

There you have it: a tour of the US’s political flashpoints by way of the federal minimum wage debate. Understand minimum wage politics and you’ll understand a great deal about American politics writ large.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/3tgbKRp

About the author

Jeannette Wicks-Lim – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Jeannette Wicks-Lim – University of Massachusetts Amherst

Jeannette Wicks-Lim is an Associate Research Professor at the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. Wicks-Lim specializes in labor economics, with an emphasis on the low-wage labor market and the political economy of racism. Her publications cover a wide range of topics, including the economics of minimum wage and living wage laws; the effectiveness of affirmative action policies; the economics of single-payer programs; and the employment-related impacts of clean energy policies.