Over the last two years, President Trump has repeatedly questioned the loyalty of Jewish people in America, claiming that voting for a Democrat would be a “great disloyalty”. In new research which looks at nearly 150 years of presidential communications, Shyam K. Sriram, Victoria Combs and Cole McNamara look at how presidents have talked about the Jewish people over the years, and find that Trump’s rhetoric is a significant departure from what has gone before.

Over the last two years, President Trump has repeatedly questioned the loyalty of Jewish people in America, claiming that voting for a Democrat would be a “great disloyalty”. In new research which looks at nearly 150 years of presidential communications, Shyam K. Sriram, Victoria Combs and Cole McNamara look at how presidents have talked about the Jewish people over the years, and find that Trump’s rhetoric is a significant departure from what has gone before.

For some, one of the more negative aspects of the Trump presidency have been his repeated statements regarding Jewish loyalty. On April 7th, 2019, he told attendees of the Republican Jewish Coalition in Las Vegas, Nevada, “I stood with your prime minister at the White House to recognize Israeli sovereignty over the Golan Heights.” Even the Times of Israel noted that the president was “appearing to conflate Jews and Israelis.” Speaking at the White House on August 20th, 2019, he asked, “Where has the Democratic Party gone? Where have they gone that they are defending these two people over the state of Israel? And I think any Jewish people that vote for a Democrat … I think it shows either a total lack of knowledge or great disloyalty.” The next day, President Trump told reporters referring to the group of Democratic Congressional legislators known colloquially as ‘The Squad’, which includes Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York, “We have a group, I call it ‘AOC plus three’ … they are anti-Semites, they are against Israel.”

He told attendees at the 2019 Israeli American Council National Summit they had “no choice” in voting for him and that Jews who voted for Democrats “don’t love Israel enough”. During a March 2020 speech by Vice President Mike Pence at the 2020 AIPAC Conference, he called Trump “the greatest friend of the Jewish people and the state of Israel to ever sit in the Oval Office.” And in September, during a call with Jewish leaders to celebrate Rosh Hashanah, President Trump said, “We really appreciate you. We love your country also.”

Yet, even as Trump argues that he is working in the interests of Jewish people, anti-Semitic attacks have accelerated over the last three years. Much of it has been blamed on President Trump’s use of philosemitism. As Joshua Shanes, Associate Professor of Jewish Studies at the College of Charleston, noted, “while the president pledges to combat anti-Semitism, he often indulges in these long-standing anti-Semitic tropes himself.” Pence has also been criticized for engaging in philosemitism; during the vice-presidential debate with Senator Kamala Harris, Pence suggested that President Trump could not possibly be antisemitic because of his “Jewish grandchildren.”

Studying how presidents have talked about the Jewish people

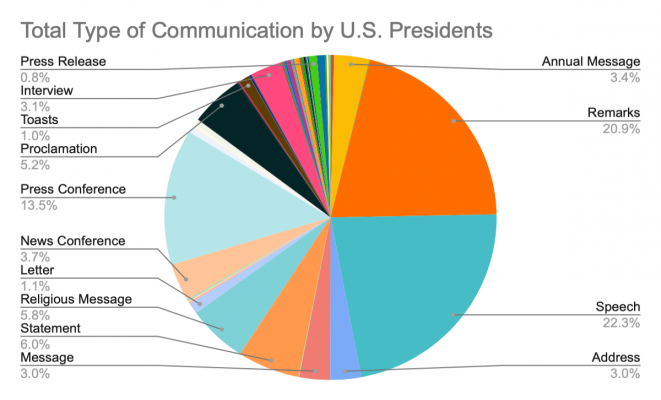

Has it always been this way? How did previous Commanders-in-Chief speak about the Jewish people? We have made an initial analysis of American presidential rhetoric and communication concerning the Jewish people. In collecting data for this research, we utilized the American Presidency Project and evaluated over two thousand available presidential communications containing the words “Jew,” “Jews,” or “Jewish” from 1872 onwards. As Figure 1 shows, these included press releases, interviews, toasts, proclamations, press conferences, news conferences, letters, religious messages, statements, messages, annual messages, remarks, speeches, and addresses. We collectively refer to these as ‘communications’.

Figure 1 – All communication by US presidents since 1872

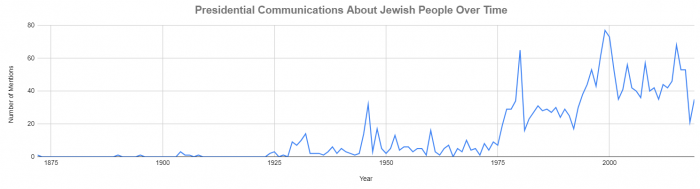

The American Presidency Project’s first mention of “Jew/Jews/Jewish” starts with President Grant in 1872. Our study analyzes that first mention all the way through the end of 2019. Figure 2 shows a gradual increase in mentions over time, with notable increases in 1946, 1980, 1999, and 2016. There is a general upward trend in overall mentions starting around 1977 and continuing to the present.

Figure 2 – Presidential communications about Jewish people, 1872-2020

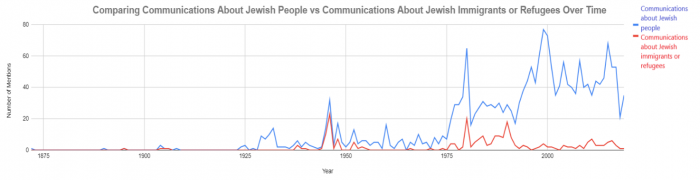

Next, we compare when presidents mention Jewish immigrants or refugees in relation to when they discuss Jews in general. The most significant results occur in 1946 and 1980, the former a midterm election year during the Truman presidency and the latter the electoral race between Carter and Reagan. It is also worth noting that 1990, a midterm election year, also had a small increase in overall references to Jewish people but saw a substantial increase in references to Jewish immigrants or refugees.

Figure 3 – Presidential communications about Jewish people in communications about Jewish immigrants or refugees, 1872-2020

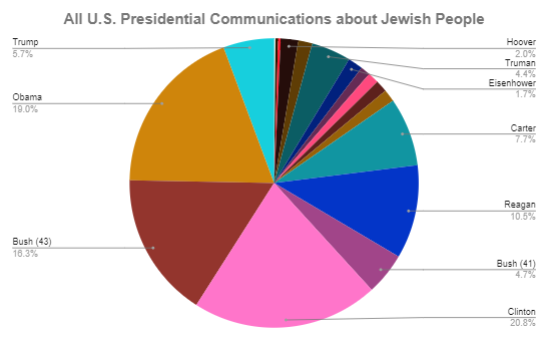

We compiled the data into two pie charts (Figures 4 and 5) to proportionally display the share of statements that presidents made in reference to the Jewish people and Jewish immigrants or refugees. It is interesting to note the vast difference in share of statements that each president has between the two figures. For example, President Clinton made the most statements about Jewish people with 20.8 percent of statements made by presidents overall; however he only made 6.1 percent of all presidential statements referring to Jewish immigrants or refugees. Presidents Reagan, Truman, Bush (41), Obama, and Carter all made up for more than 10 percent of all statements referring to Jewish immigrants or refugees.

Figure 4 – All US presidential communications about Jewish people, 1872-2020

Figure 5 – All US presidential communications about Jewish immigrants or refugees, 1872-2020

We acknowledge that some limitation exists in regard to the data because the American Presidency Project has less correspondence generally from earlier presidencies, and importantly, the nature of technology and presidential communications has evolved over time. As technological advances have occurred, presidents have been able to distribute more communications with higher frequencies and broader reach.

How presidents have spoken about the Jewish people has changed over time

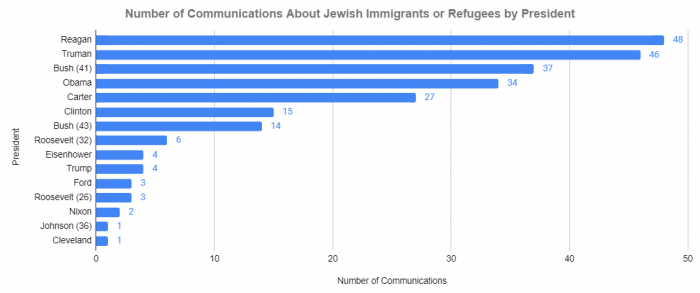

Both Presidents Reagan and Truman were the most likely to reference Jewish immigrants or refugees followed by Bush (41), Obama, and Carter. Reagan’s role in acknowledging Jewish oppression in the Soviet Union was established as early as 1983 and his administration was seen as a vital ally. After his death in 2004, journalist Ron Kampeas noted that Reagan’s presidency was “seen by many as halcyon days for Jewish issues in foreign policy, principally because of the effects of Reagan’s greatest triumph: the collapse of the Soviet bloc.”

Figure 6 – Number of Communications about Jewish Immigrants or refugees by President

Initially, we had understood this rise in mentions during the Truman administration as directly related to the Holocaust and World War II. A more likely explanation comes from the issues between Israel and Palestine, which does connect to the aftermath of World War II, but Truman does not explicitly reference the Holocaust within these communications.

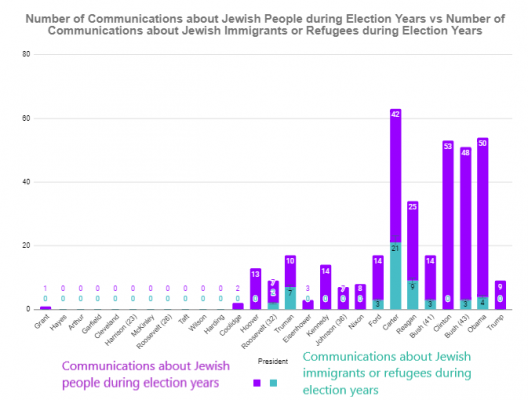

Finally, we examined the significance of elections on presidential Jewish rhetoric. The teal bar in Figure 8 shows the number of communications made in reference to Jewish immigrants or refugees, while the purple bar displays the remaining communications made about Jewish people. Like most of our other data, this graph displays a gradual increase in communications about Jewish people over time, with the data about Jewish immigrants or refugees being a lot less prevalent. President Carter is a clear leader in having 21 communications about Jewish immigrants or refugees during the elections of 1976 and 1980.

Figure 7 – Number of communications about Jewish people during election years vs number of communications about Jewish immigrants or refugees during election years

In a recent article for the USAPP blog, one of the authors of this article, Shyam K. Sriram, commented on the decline in refugee admissions under President Trump compared to past presidents. In conjunction with our findings here, we see a larger pattern within Trump’s rhetoric focused on creating a moral panic about Jews, Jewish immigrants, and immigrants as a whole. This is in steep contrast to the presidencies of Truman, Carter, Clinton, and Reagan who played a more pivotal role in supporting the Jewish American experience and connecting it to global and domestic crises.

- “Presidential podium” by Gage Skidmore is licensed under CC BY SA 2.0

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2KUAYDq

About the authors

Shyam K. Sriram – Butler University

Shyam K. Sriram – Butler University

Shyam K. Sriram is a visiting assistant professor in the Department of Political Science at Butler University.

Victoria Combs – Butler University

Victoria Combs is an undergraduate student at Butler University.

Cole McNamara – Butler University

Cole McNamara is an undergraduate student at Butler University.

What is the difference?