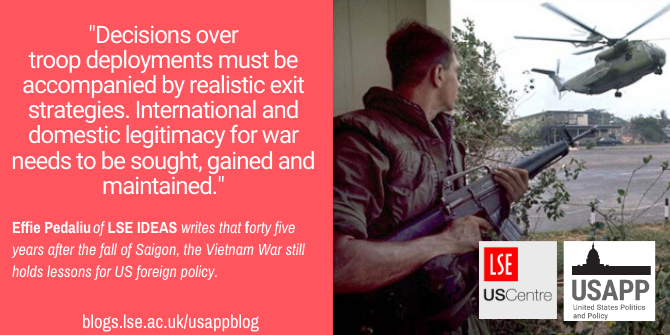

In late April 1975, the last remnants of the American presence in South Vietnam were removed as the North Vietnamese Army prepared to take over Saigon. Effie Pedaliu writes that even 45 years later, the fall of Saigon has lessons for US foreign policy, such as the need to plan an exit strategy in armed conflicts, and the importance of diplomacy for mending relationships between former enemies.

In late April 1975, the last remnants of the American presence in South Vietnam were removed as the North Vietnamese Army prepared to take over Saigon. Effie Pedaliu writes that even 45 years later, the fall of Saigon has lessons for US foreign policy, such as the need to plan an exit strategy in armed conflicts, and the importance of diplomacy for mending relationships between former enemies.

Forty-five years ago, on 30 April 1975, the ‘fall of Saigon’ signified the end of the Vietnam War – a war of challenging and lingering legacy for both America and Vietnam. Difficulties over how to remember the ‘fall of Saigon’ and the Vietnam War arise not just from contested memories, political manipulation and intellectual disputes, but also from how individuals, groups and nations deal with the ramifications of what was a profoundly divisive and traumatic experience. The war ended with more than 58,000 Americans dead, and at least three million Vietnamese civilians and combatants on both sides of the conflict killed (though numbers are not precise). Billions of US dollars had been spent and sizeable tracts of Vietnam sprayed with two million gallons of ‘Agent Orange’, some containing dioxins that continued to affect the health and economic well-being of the Vietnamese people well after the war was over. No wonder that the Vietnam War has been described as ‘the war with the difficult memory’. The meaning of the ‘fall of Saigon’ has since been interpreted through many competing filters.

How the Vietnam War ended in Saigon

The Vietnam War ‘is finished as far as America is concerned,’ President Gerald Ford announced at Tulane University on 23 April 1975. For weeks up to that point Saigon, the capital of the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam), the entity that was born from the embers of the French empire, civil war and the intensifying application of the US policy of containment in South East Asia to stop ‘dominoes’ from falling, had feared an imminent attack. Intelligence reports backed this. Daily, commercial airlines and US Air Force aircraft carried hundreds of Vietnamese and Americans out of the country.

By 27 April, the People’s Army of Vietnam had encircled Saigon, though Graham Martin, the US ambassador there, was in full denial. On 28 April, he wrote to Henry Kissinger, the US Secretary of State, predicting that the US could hold on to Saigon ‘for a year or more.’ He even ordered American officials to stop using empty cargo space on flights to help their South Vietnamese friends escape the doomed state.

Operation Frequent Wind was the code name given to the final phase of evacuating American civilians, other Westerners and ‘at-risk’ Vietnamese from Saigon. What was originally planned as an airlift became ‘the day of the choppers’. The mass helicopter evacuation from designated rooftops started late, after midday, on 29 April and was curtailed later that evening.

Even the order for sensitive documents to be shredded was delayed. As one CIA officer put it, there was ‘top-secret confetti in the embassy courtyard’ – the result of bags being torn open by the comings and goings of the helicopters. At 03:45hrs, on 30 April, the order came from President Ford that there would be only nineteen ‘lifts’ and that only the Ambassador, Embassy staff and Americans would be taken out. The US Marines carried out many more. As soon as Martin and his staff boarded their helicopter at 04:58 hrs the code ‘Tiger is out’ was issued creating confusion among other helicopter pilots that the mission had been completed.

Image by Dirck Halstead – U.S. Marines in Japan Homepage [1] photo 050516-m-3509k-007 [2], Public Domain, Link

The guard detachment of Marines at the Embassy would not be pulled from the Embassy rooftop until 07:53 hrs, just three hours before North Vietnamese tanks smashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace. ‘They literally forgot about us,’ Juan Valdez, the detachment’s commander, would say in an interview in 2015. The largest helicopter evacuation in history had taken place among scenes of disaster and chaos and ended up leaving behind many of those who had been assured they ‘would [not] be left behind’.

In parallel, attempts at escape over water were taking place. The 7th US Fleet was not prepared for what it now encountered – a massive flotilla of anything that could float attempting to sail away from South Vietnam and teeming with desperate people. USS Kirk switched its naval escort mission to a humanitarian rescue operation, but overcrowding on the American ships meant that many small boats would not be saved. The US Navy and Marines jointly evacuated more than 30,000 Vietnamese refugees.

The Vietnam War was over. The US had first become entangled in Vietnam to show its determination to uphold containment worldwide and to reassure its allies. This ‘Black April’ – as it would come to be known by Vietnamese in the US – however, ended with the hegemonic power of the West quitting Indochina neither as a victor nor as a liberator and, above all, not as an ally that was prepared to keep its promises. The US departed Vietnam as a country deeply demoralised and divided. America needed to recover, or as President Ford put it: ‘It’s over. Let’s put it behind us’.

After the end

The day of ‘the liberation of Saigon’ on 30 April 1975 was North Vietnam’s moment of triumph – ‘the American War’ was about to end. The flag of the National Liberation Front was raised over the Presidential Palace. Duong Van ‘Big’ Minh, made President of South Vietnam just two days before, waited patiently to hand over power only to be told: ‘You cannot hand over what you no longer have’.

That day, Saigon basked in glorious sunshine after the previous heavy rain that had so hampered the US evacuation effort. At 05:00 hrs, the street music switched swiftly from ‘White Christmas’ to ‘Red Music’. There was apprehension. Some soldiers and politicians committed suicide fearing the future, whilst the majority of people hoped that things would be alright.

The expected blood bath did not happen. ‘Liberation has been everyone’s victory. … The only ones who have been defeated are the Americans’ was how each political re-education session was to begin for the numerous South Vietnamese detained in camps. City dwellers were pushed to take up farming in the countryside as collectivization was implemented to transform Vietnam into a socialist country. The dream was to be short lived. The legacy of the war and the policies of the new government had disastrous effects on the economy. By 1978 a new wave of ‘boat people’ took flight. By 1986, Vietnam moved to experiment with a more market-based economy. The author, poet and journalist James Fenton, who was in the first tank that entered the Reunification Palace, reflected later, ‘We had been seduced by Ho’.

There were no happy endings for many Vietnamese. Reconciliation has still not occurred – even now. In 2015, Vietnamese commemorations of ‘the Fall of Saigon’ – since renamed Ho Chi Minh City – displayed many pictures of American soldiers hugging North Vietnamese soldiers, but there was not one of a North Vietnamese soldier embracing a South Vietnamese soldier.

Although the last American forces had left South Vietnam in 1973, the ‘fall of Saigon’ was perceived as a David versus Goliath moment in the history of the Cold War: a small country had defeated a superpower. Like all critical events in history its echoes reverberated for many years to come. Its influence on the final outcome of the Cold War was minimal, yet ‘the fall of Saigon’ had a series of international implications. America wallowed in its Vietnam Syndrome and in time the ‘liberals, the Press and the Congress’ would be blamed for the failure in Vietnam now experienced as both defeat and betrayal. The limitations of the policy of containment had been laid bare. Its economic successes were not replicated in the military field; Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos became communist. The international prestige of the US lay in tatters as public opinion turned against it. Anti-Americanism rode so high around the world that the institutions of European integration awoke from their ‘euro-sclerosis’ to save the West by elaborating ‘European values’ and stabilising the Southern European democracies now rid of their dictatorships.

Moreover, the transnational movements aiming to protect human rights and uphold civil liberties that had been spurred by the Vietnam War grew in strength. Nixon’s destruction of the Bretton Woods system to fix the economic difficulties facing the US as a result of the war undermined European economies and when the oil shock of 1973 came it found them and the US less able to mitigate the blow. The rise of the Third World seemed unstoppable and Communism and the Soviet Union appeared to be stronger than they were. The NATO allies were left less confident in the willingness of the US to defend them, though in retrospect it transpired that collective security trumped any allied disagreements.

What have we learned from Vietnam?

Wars do not end the moment the guns fall silent or when cities fall, however ‘stunningly’. It is at this moment that the search for lessons and the battle for ‘memory’ begin as the desire to avoid future disaster kicks in. Since 1975, political commentators and politicians have blamed successive US administrations for not learning from the past. Drawing lessons though, that could apply to other conflicts from a war that was itself premised on the ‘wrong lessons’ learnt from the Truman Doctrine and the Greek Civil War, is at best a process full of pitfalls. For decades, even today, the conclusions of voluminous and impressive scholarly works on Vietnam – covering both sides of the conflict – have often been weaponised in cultural and political wars of words.

The most durable takeaways from the Vietnam War and ‘the fall of Saigon’ may be considered to be rather prosaic. In the environment of the Cold war, despite scepticism and reluctance over American involvement in Indochina, all US administrations from Truman to Nixon decided they had no other option but to be there. However, for wars to be winnable, war aims and what constitutes an acceptable victory need to be clearly defined. Decisions over troop deployments must be accompanied by realistic exit strategies. International and domestic legitimacy for war needs to be sought, gained and maintained. Finally, diplomacy can, in the long run, fix even the most vexatious relationships. By normalising their relations in 1995, just 20 years after the fall of Saigon, the US and Vietnam have succeeded in building an increasingly productive relationship in the economic, political, education and security fields.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: https://bit.ly/2M0MAlV

About the author

Effie G. H. Pedaliu – LSE IDEAS

Effie G. H. Pedaliu – LSE IDEAS

Effie G. H. Pedaliu is a Visiting Fellow at LSE IDEAS and co-editor of the Palgrave book series, Security Conflict and Cooperation in the Contemporary World. She is the author of ‘Transatlantic Relations at a Time When “More Flags” Meant “No European Flags”: The US, its European Allies and the War in Vietnam’, 1964-1974’ in International History Review (2013) and co-editor of The Greek Junta and the International System: A Case Study of Southern European Dictatorships, 1967-1974 (London: Routledge, 2020).

re: many pictures of American soldiers hugging North Vietnamese soldiers, but there was not one of a North Vietnamese soldier embracing a South Vietnamese soldier.

This is an American gesture. Vietnamese do not hug. Nor do we say “I love you” out loud or bring “closure.”

Ms. Pedaliu, this was an AMERICAN war, not a Vietnamese war. ARVN soldiers were merely pawns or cannon fodder. It is the bitter lesson of being used by the US of America, sad to say that you do not even know this.