In the current polarized environment of contemporary US politics, compromise between those from different sides of the political aisle seems hard to come by. In new research, James M. Glaser, Jeffrey M. Berry and Deborah J. Schildkraut look at the role of education as a factor in whether people support political compromise. They find that while those with a college education are more likely to support political compromise, this does not hold for conservatives, potentially because it may enhance their sense of individualism and skepticism.

In the current polarized environment of contemporary US politics, compromise between those from different sides of the political aisle seems hard to come by. In new research, James M. Glaser, Jeffrey M. Berry and Deborah J. Schildkraut look at the role of education as a factor in whether people support political compromise. They find that while those with a college education are more likely to support political compromise, this does not hold for conservatives, potentially because it may enhance their sense of individualism and skepticism.

Education is the universal solvent. So wrote political scientist Phillip Converse about the importance of formal education to our democratic functioning. For so many reasons, education contributes to political sophistication. It gives individuals more information to draw upon in making political decisions, and more information also feeds political interest. Educated people are most likely to be surrounded by other educated people, magnifying its effect via social pressure or stimulation. Little wonder that most social scientists include education in their models of political behavior, even if it is not the centerpiece of their inquiry.

Education, not surprisingly, makes an important contribution to the acceptance of political compromise in the US. At a moment of great polarization in American politics, with bipartisanship hard to come by in policy making, political dialogue characterized more by outrage than civility, and politicians rewarded by voters more for “sticking to their guns” than for reaching consensus, we believe – and many educated people agree – that we could use more compromise and less intransigence.

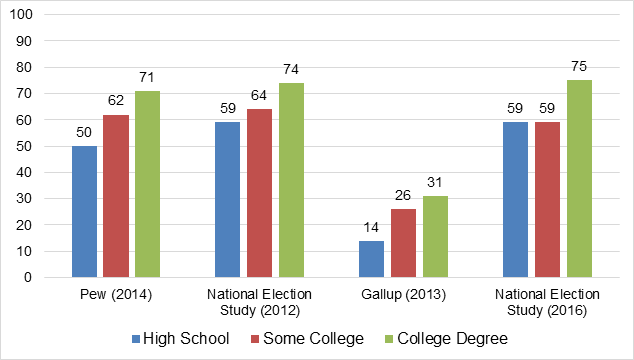

In new research, we show that better educated people accept the value of political compromise more than those with less education. For example, as Figure 1 shows, when Pew asks whether respondents “like elected officials who make compromises with people they disagree with” or “like elected officials who stick to their positions,” the college educated are 21 percentage points more likely to approve compromise than those with just a high school education. It is a finding replicated many times over, by different pollsters, with different question wordings, and at different moments in time, and it is one that holds up when we control for various other factors such as age, gender, and race.

Figure 1 – Percent who prefer compromise by educational attainment

We note that the effect of education on compromise is not because educated people hold their values and policy preferences less dear or are less likely to push their point of view than those with less education. Indeed, political scientists show over and again that better educated people are more politically principled. Instead, we argue that formal schooling leads people to more fully appreciate that the mechanisms of democratic government require compromise in order to produce policy outcomes acceptable to broad swaths of society.

As we dig deeper, however, the relationship between education and compromise is a conditional one. By this, we mean that it does not work the same way for all groups of people. Notably, in an American context, it is self-identified conservatives who stand out. Conservatives begin with greater hostility to compromise than moderates and liberals, and we show in other work that this might be related to the fact that conservatives are more often defenders of the status quo while liberals push for change. According to prospect theory, the fear of loss is stronger than the prospect of a gain for many people, and this, indeed, seems to be at work in how Democrats and Republicans, liberals and conservatives, approach compromise in policymaking. It is also the case that conservative media like Fox News and right-wing talk radio disparage compromise and compromisers more than liberally-tinged media do, providing distinctive opinion leadership.

Photo by Mikael Kristenson on Unsplash

But our point extends beyond this. Education contributes to higher levels of approval of compromise among liberals and moderates, but much less so for conservatives. Indeed, when studied in a context which includes a variety of variables, among conservatives, the relationship of education and support for compromise is negative. All else the same, better educated conservatives are less supportive of compromise in principle than less educated conservatives.

What is it about conservatives that leads to this result? We argue that education matters for conservatives as well as for liberals and moderates. For everybody, it should encourage recognition of the value of compromise to peaceful and acceptable outcomes. But for conservatives, we assert, education also brings to fore other considerations that blunt the acceptance of compromise. In other words, education matters for conservatives, but it matters in two competing ways.

These other considerations include an attachment to individualism and skepticism toward government, two sets of beliefs that we argue might lead one to question the importance of political compromise. We hypothesize that an individualist mindset might lead one to devalue outcomes that aggregate competing interests and represent a broad societal consensus. Likewise, disliking and distrusting government might make one less approving of those things that make government work better.

When we account for these notions – that educated conservatives are indeed more likely to hold than less educated conservatives – the relationship of education and approval of compromise diminishes to insignificance. The bottom line is that education contributes to a belief in the value of compromise, but for conservatives, these other ideas intervene leading to our “curious” result.

As we have promoted these findings at conferences and in writing, we have been criticized by those who take issue with our basic assumption. Our critics contend that compromise may not be the virtue we argue it to be. One commentator at a seminar, offering an exaggerated example to make his point, raised the specter of Neville Chamberlain compromising with and capitulating to the Nazis. Others have made this point in the context of the divisiveness, polarization and personalization of current American politics, where compromise with the other side feels like a deal with the devil.

We understand this critique, and indeed we do place an inherent value on compromise. While, of course, not all compromises are worth pursuing, we argue that there is real value in democratic compromise. How can government work in a pluralistic society without it? How can policy makers collect and sift through all the different interests and beliefs in a diverse country like the US? How can minorities be heard and their interests represented?

Certainly, some of our perspective comes from living in and studying politics in a presidential system. The model established by the American founders encouraged – compelled – the creation of coalitions within legislative processes. And while it is true that government in parliamentary systems does not encourage cross-party compromise once a government has been formed and an opposition set, party coalitions require compromise as well, and continued tending. If compromise is not a panacea for all that ails present-day democracies, surely it makes some important things possible, and this is something that education, somehow, some way, leads people to recognize.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Education and the Curious Case of Conservative Compromise’ in Political Research Quarterly.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2NJywi1

About the authors

James M. Glaser – Tufts University

James M. Glaser – Tufts University

James M. Glaser is Professor of Political Science and Dean of the School of Arts and Sciences at Tufts University. His books include Race, Campaign Politics, and the Realignment in the South, The Hand of the Past in Contemporary Southern Politics, and Changing Minds if not Hearts: Political Remedies for Racial Conflict.

Jeffrey M. Berry – Tufts University

Jeffrey M. Berry – Tufts University

Jeffrey M. Berry is Skuse Professor of Political Science at Tufts University. His books include The Outrage Industry, Lobbying and Policy Change, and A Voice for Nonprofits.

Deborah J. Schildkraut – Tufts University

Deborah J. Schildkraut – Tufts University

Deborah J. Schildkraut is Professor of Political Science at Tufts University. Her books include Americanism in the Twenty-First Century: Public Opinion in the Age of Immigration and Press One for English: Language Policy, Public Opinion, and American Identity.