Research has shown that detention before trials contributes to broader patterns of inequality in the criminal justice system. In new research, Brandon P. Martinez, Nick Petersen, and Marisa Omori look at how pretrial detention length contributes to this inequality. Their analysis of pretrial detention patterns in Miami-Dade County, Florida, finds that Black people are more likely to have higher bond amounts and spend longer in pretrial detention, and that spending longer in pretrial detention is linked with more severe sentences.

Research has shown that detention before trials contributes to broader patterns of inequality in the criminal justice system. In new research, Brandon P. Martinez, Nick Petersen, and Marisa Omori look at how pretrial detention length contributes to this inequality. Their analysis of pretrial detention patterns in Miami-Dade County, Florida, finds that Black people are more likely to have higher bond amounts and spend longer in pretrial detention, and that spending longer in pretrial detention is linked with more severe sentences.

Pretrial detention has received increased attention in recent years, partly due to documented abuses of people—particularly people of color—who were detained pretrial, such as Kalief Browder and Sandra Bland. Findings from previous research highlight the racial and ethnic inequalities in pretrial detention and how they contribute to broader patterns of inequality in the criminal justice system. For example, people of color are more likely to be detained pretrial, be assigned higher bond amounts, and be held on bond. The time lost for defendants held in pretrial is invaluable and can inhibit their everyday lives, such as showing up to work, engaging in their community, and caring for their children and family.

Until now research has tended to focus on the effect of bond decisions rather than pretrial detention time. Previous findings have suggested that pretrial detainees have an increased incentive to quickly plead guilty in order to be released. The length of time people are detained before their trial also affects the trial itself. Because there is uncertainty surrounding detention length, this can afford prosecutors more leverage in the plea-bargaining process by coercing people to plead guilty. Time detained pretrial, therefore, is not only a practical matter for people seeking to be released, but also carries a stigma of that may result in more punitive outcomes.

Pretrial detention in Miami-Dade County

In new research we examine how the length of time people are detained before their trials contributes to racial and ethnic inequality in the criminal justice system. To do so, we analyze data on all adults arrested and booked on felony, misdemeanor, or ordinance charges in Miami-Dade County, Florida, between 2011 and 2015. We looked at detailed information about bond amounts and pretrial detention time, as well as information about people’s court case outcomes. Many people in Miami-Dade County are detained pretrial, though those charged with low-level crimes often get a promise to appear in court and are not detained. People charged with more serious crimes may be denied bond or assigned a bond by a judge who may account for a person’s prior offenses, flight risk, and any arguments/evidence presented by public defenders or prosecutors.

Detention time is a key driver of criminal justice inequality

In general, we find that Black people (especially those who are Latinx) who are arrested have higher bond amounts and spend more time in pretrial detention relative to White people. While there are generally larger differences between Black and White people, we also find some differences by ethnicity. Compared with White non-Latinx people, Black non-Latinx people have 15 percent higher bond amounts and spend 12 percent more days in pretrial detention, whereas Black Latinx people have 18 percent higher bond amounts and spend 18 percent more days in pretrial detention. White Latinx people also have larger bond amounts than White non-Latinx people, though they spend less time detained pretrial.

We then examined the relationship between bond amounts and time detained pretrial. Our analysis indicates that a 1 percent increase in bond amount corresponds with an 11 percent increase in detention time, controlling for differences in individual-level characteristics (such as age and gender) and case characteristics (such as prior conviction and type of charge). However, we also find that racial and ethnic disparities in bond amounts contribute to inequalities in detention time. This relationship between time and money further disadvantages Black people.

Photo by Bill Oxford on Unsplash

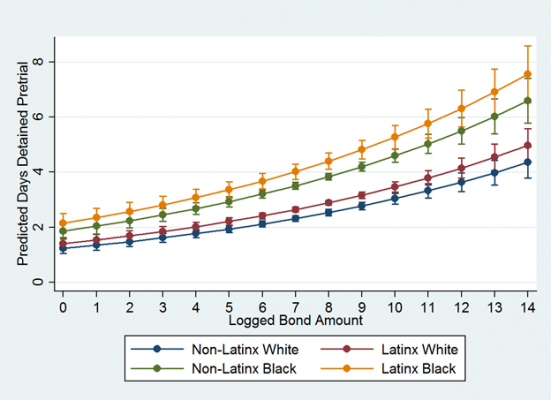

In Figure 1, we show that increases in bond amount are related to increases in pretrial detention time for all people. However, the effect of bond amount on detention time is larger for Black people, especially Black Latinxs. Racial inequality (and to some degree, ethnic inequality), therefore, worsens as the bond amount increases. Small differences in bond amounts between Black and White people have a compounding effect on their time detained pretrial. Although such small initial differences in bond amounts represent individual-level decisions based on institutional tools (bond schedules and risk assessments), they produce and reinforce large-scale racial and ethnic inequality over time.

Figure 1 – Predictions for pretrial detention time by bond amounts

In contrast to defendants who are detained pretrial, those released pretrial have less pressure to plead guilty to get out of jail so they can return to work, school, or their families and friends. As such, inequalities in pretrial detention are also important for understanding a person’s likelihood of conviction and incarceration. Indeed, we find that lengthier pretrial detention stints lead to more severe sentencing sanctions. Figure 2 below shows how the likelihood that a person is incarcerated increases with the number of days they were held pretrial. The cumulative and compounding effect of time detained pretrial on the likelihood of incarceration disadvantages Black people compared with White people. This exponential growth in incarceration likelihood and increasing racial-ethnic inequality illustrates how small initial differences can accumulate over time to reinforce inequality.

Figure 2 – Predictions of incarceration by pretrial detention time

How pretrial detention contributes to inequality in the justice system

Our findings join a wave of recent research that highlights how pretrial detention contributes to racial-ethnic inequality in the criminal justice system. Throughout our analysis, we emphasize that individual-level or micro-level actions (e.g. judicial bond and release decisions) can and do become drivers of cumulative inequality. As cumulative advantage theories in the social sciences hypothesize, and as our findings show here, small differences in bond amounts compound across time to create an increasingly wider gap between Black and White people. Moreover, the accumulating effect of pretrial detention time on conviction and incarceration outcomes is consistent with similar cumulative understandings of racial-ethnic inequality.

Given the scale of pretrial detention in the US criminal justice system, what can be done about these stark inequalities? Bail funds provide one opportunity to move defendants out of pretrial detention, so that they can await their trail outside of the confines of a jail. Generally, bail funds are used by pay a person’s bond, which is returned upon the completion of the case. Public policy initiatives have also addressed the punitive effects of pretrial detention. For example, several jurisdictions, including California, have recently reformed or abolished cash bail. Reducing the use of pretrial detention would follow a general trend of decarceration, such as in the case of realignment policy in California and the progressive prosecutor movement. As our findings illustrate, addressing pretrial detention is of paramount importance for confronting racial and ethnic inequality in the criminal justice system.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Time, Money, and Punishment: Institutional Racial-Ethnic Inequalities in Pretrial Detention and Case Outcomes’ in Crime & Delinquency.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2Rlzm5j

About the authors

Brandon P. Martinez – University of Miami

Brandon P. Martinez – University of Miami

Brandon P. Martinez is a Sociology doctoral candidate at the University of Miami studying the sociology of housing, immigration, and the criminal justice system. Currently, he is studying the housing outcomes and choices of the second generation.

Nick Petersen – University of Miami

Nick Petersen – University of Miami

Nick Petersen is an assistant professor of Sociology and Law at the University of Miami. He holds a PhD from the University of California, Irvine in Criminology, Law, and Society. His research focuses on racial stratification within criminal justice institutions.

Marisa Omori – University of Missouri–St. Louis

Marisa Omori – University of Missouri–St. Louis

Marisa Omori is an assistant professor of Criminology and Criminal Justice at the University of Missouri–St. Louis. She received her PhD from the University of California, Irvine in Criminology, Law, and Society. Her research focuses on the racialization of crime control, including racial inequality within criminal justice institutions and drug use and punishment.