The received wisdom in political science is that framing messaging in a negative way – warning about potential losses and threats – is more effective at mobilizing people to be more politically engaged that positive messaging. In new research, Christopher Mann and colleagues find that outside of laboratory experiments, when real political behaviors are measured in the field, negative frames are no more effective at motivating political action than positive frames.

The received wisdom in political science is that framing messaging in a negative way – warning about potential losses and threats – is more effective at mobilizing people to be more politically engaged that positive messaging. In new research, Christopher Mann and colleagues find that outside of laboratory experiments, when real political behaviors are measured in the field, negative frames are no more effective at motivating political action than positive frames.

When seeking to mobilize Americans to vote, contribute, contact elected officials, or take other action, political elites often use rhetoric about loss, damage, threat, or loss (which is called negative framing): loss of jobs or health care; damage to the environment; threats to abortion rights, gun rights, or civil rights. The use of this negative framing in the communications that is often used to mobilize support is grounded in many social science laboratory experiments that negative frames are more effective than positive frames (benefits, improvements, or gains). But effects seen in laboratory experiments from framing often fail to materialize in real-world settings, and there is scant research on whether negative frames are more effective in motivating real-world political action.

In new research with Kevin Arceneaux and David Nickerson, we conducted four field experiments in partnership with civic organizations delivering messages randomly assigned to negative or positive frames describing real policy proposals and encouraging real-world political actions: voter turnout and contacting elected officials. We find little-to-no evidence that negative frames are more effective than positive frames for motivating real-world political action.

Economics, psychology and political science have developed a strong theoretical foundation that negative framing of political communication tends to be more effective at motivating political action than positive framing. First, people tend to notice and retain negative information more than positive information, so emphasizing negative impacts of policy debates tends have a stronger and longer effect on policy opinions than emphasizing the positive. Second, people prefer policies that avoid losses more than policies that promote gains because “losses loom larger than gains.” Third, people resist policy proposals changing the status quo because they value the things that they already have more than the things that they do not.

Photo by Volkan Olmez on Unsplash

Why would negative frames fail to be more effective for real-world political behavior? The laboratory experiments usually involve abstract situations or games about taking from or contributing to a public good, where there are no meaningful personal costs. In the real-world non-political behaviors studied, like encouraging healthy behaviors, the behavioral outcome provides a direct benefit to the message recipient to offset direct costs. Real-world political behavior may be different because people bear meaningful personal costs to take political action that benefits the public good but has no direct personal benefit. The scant available evidence about real world political behavior is mixed. For example, a previous field experiment found that compared to a positively framed message, negative framed messages reduced likelihood of sending a postcard to the President but increased contributions to a political organization.

In our four field experiments, the negative frames combined general negative information, loss frames about policy consequences, and argued for the status quo. This approach should make the negative frame as powerful as possible from a theoretical standpoint, as well as reflect real-world political messaging strategies. Figure 1 shows the negative and positive frames from one of our experiments encouraging citizens to contact their state’s governor about a proposed environmental policy change.

Figure 1 – Field Experiment 2 Script

| Positive Frame | Negative Frame |

| Last year, <state> adopted a strong rule that reduces carbon pollution by the biggest polluters in the state…

Unfortunately, Governor <name> wants to overturn the rule that reduces carbon pollution in <state>… By keeping the rule, we can create good-paying jobs in the clean energy sector—at a time when we desperately need them. We’ll also improve our air quality and become a national leader in tackling climate change. |

Last year, <state> adopted a strong rule that reduces carbon pollution by the biggest polluters in the state…

Unfortunately, Governor <name> wants to overturn the rule that reduces carbon pollution in <state>… If the rule is dismantled, we will lose the good-paying jobs in the clean energy sector—at a time when we desperately need them. We’ll also make the threats of climate change worse—including greater risks of wildfires and drought. |

Our initial voter mobilization experiment used live phone calls encouraging turnout among registered voters in four states. We compared the turnout of registered voters contacted with a randomly assigned positive or negative framed message about policy consequences of voting. Each message increased turnout compared to the control group, but we found no support for negatively framed messages being more effective than positively framed messages.

Next, we conducted three field experiments in a novel context: phone calls by a policy advocacy organization to recruit people to contact an elected official (known as “patch-through calls”). Contacting elected officials is an important political activity and patch-through calls are a common tactic of policy advocacy organizations, but these experiments are the first of their kind. These experiments have the advantage of measuring real-world political behavior (connecting the call to the elected official) immediately after receiving the randomly assigned negative or positive framed message.

Experiments 2–4 were part of a policy advocacy effort by our partner organization. Households were randomly assigned to receive a positive or a negative frame about consequences of a proposed policy change before being asked to “patch through” to the Governor’s office. Experiment 2 used the scripts in Figure 1. Experiment 3 used similar scripts about a different environmental policy. A postponement in the state’s rule-making process allowed us to conduct Experiment 4 using the same scripts three months later – a rare opportunity for exact replication.

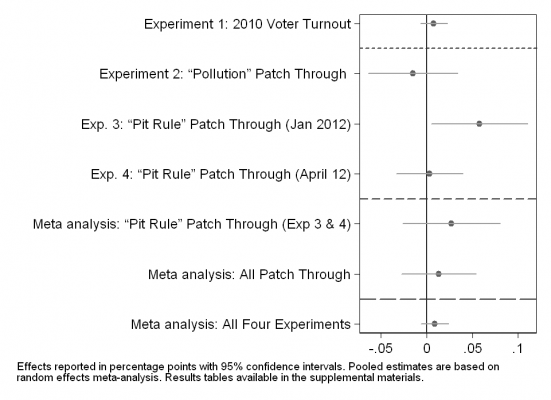

Figure 2 shows the results of all four experiments. Only Experiment 3 found statistically significant evidence that a negative frame was more effective than a positive frame, but this result failed to be replicated in Field Experiment 4. The pooled effect from Experiments 3 and 4 is far from statistically significant. The meta-analyses at the bottom of the figure combining the three patch-thru call experiments and then all four experiments show no effect on average across the experiments.

Figure 2 – Negative Frame Treatment Effect Estimates and 95-Percent Confidence Intervals for Field Experiments 1–4

Field experiments like ours cannot prove conclusively that negative frames are no more or less effective than positive ones. Only additional field experiments can determine if an alternative wording of frames could be more successful, and those would be exciting findings. However, the language in our treatments was constrained by legal and political considerations of our partner organizations that we believe are commonplace in political communication. If producing larger results requires more potent negative frames, then negative framing cannot provide a general tool for motivating political action because such frames are unlikely to be employed in the real-world.

It may be somewhat comforting that people are not easily manipulated into real-world political action by political elites simply shifting frames. If political elites heed our findings that negative framing is no more effective than positive frames of policy consequences for motivating the public to participate in politics, perhaps politics will seem a little less gloomy and threatening.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Do Negatively Framed Messages Motivate Political Participation? Evidence From Four Field Experiments’, in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2m0sgHA

About the author

Christopher B. Mann – Skidmore College

Christopher B. Mann – Skidmore College

Christopher B. Mann is an assistant professor of Political Science at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, NY. His research focuses on field experiments on increasing political participation and on the impact of changes in election administration on political participation.