In new research, Elizabeth Korver-Glenn examines why racial residential segregation has become such a stubborn problem in America – and in some cases has actually gotten worse. Using ethnographic research of real estate agents, developers, lenders, and appraisers in Houston, Texas, she finds that their routines and policies often exclude people of color as prospective home buyers based on stereotypes, and that this exclusion compounds at every stage of the house buying process.

In new research, Elizabeth Korver-Glenn examines why racial residential segregation has become such a stubborn problem in America – and in some cases has actually gotten worse. Using ethnographic research of real estate agents, developers, lenders, and appraisers in Houston, Texas, she finds that their routines and policies often exclude people of color as prospective home buyers based on stereotypes, and that this exclusion compounds at every stage of the house buying process.

Racial residential segregation is a durable feature of American cities. Indeed, despite apparent, if modest, declines in racial discrimination and socioeconomic inequality as well as less overt racial prejudice and greater tolerance for racial diversity among Whites, racial segregation has remained relatively stagnant. In metropolitan areas with increasing minority populations, such as Atlanta, Houston, and Miami, some groups have actually become more segregated over the past 20 years.

My recent research tackles this puzzle head-on by addressing several key gaps in segregation research. First, where most segregation research examines patterns of residential mobility and stability, I examined the process of housing exchange. Second, while most research on housing discrimination focuses on a single stage of housing exchange (e.g. real estate brokerage or mortgage lending), I examined how discrimination unfolds across multiple stages of the exchange process. Finally, rather than emphasizing the persistence of individual racial prejudices, I focused on the formal and informal organizational routines or (unofficial) policies that may enable such prejudices.

Using the Houston, Texas housing market as a case study, I employed multiple methods, including a year of ethnographic research among 13 real estate agents and developers, 102 interviews with agents, developers, lenders, and appraisers, among others, and supplemental quantitative analyses, to address these gaps. I found that racial inequality in housing markets persists for several reasons, two of which I will highlight.

First, there are key organizational routines and policies, such as generating business through social networks, use of ‘market area’ maps, and discretion, that enable or even encourage housing market professionals to use widely shared racial stereotypes as they go about their work. These routines and policies are not always formally expressed, but they are common, expected ways of engaging in housing market work that support stereotyping and unequal treatment, even if this is unintentional.

For example, individual brokerage firms all the way up to the National Association of REALTORS® strongly encourage agents to assess risks to their personal safety or financial profit. There are even entire real estate continuing education courses dedicated to these topics. In practice, brokerage organizations’ regular reinforcement of potential financial or physical danger meant that agents routinely gauged the perceived financial and safety risks of prospective home buyers. Moreover, they did so by applying widely shared racial stereotypes about Asian, Black, and Hispanic home buyers when answering phone calls or hosting open houses, among other situations. “Anthony” a middle-aged White real estate agent, explained it this way:

When I was in real estate . . . there was something called prime desks. So you would be on the desk and then if a call came into the company for someone saying, “Hey, I’m looking at this house. I’m driving by this house . . . and want to know about this property,” and if you’d get a call and it was an Asian person you’d usually take the number and you’d never call them back. . . . Because they tend to use—because they would say—they’d get all the information, you may go show them the house, and then they’d come back later with their cousin or their aunt or their uncle. . . . Yeah, I mean I think about when I worked at my big firm down here…. I mean people would—an African American would call or come to an open house—first of all, they would think they were there to steal and they would usually call someone for backup because it was like “Uh- uh!” [startled sound], you know, and they would—I can think—many times, they wouldn’t take that person seriously, or they wouldn’t put the time into it, or they wouldn’t take the call.

In this example, prospective Asian buyers were perceived as a financial risk (especially by White agents) and prospective Black buyers were perceived as a risk to personal safety (especially by White agents). These perceptions then affected how White agents in particular responded to, serviced, or avoided servicing, these prospective customers of color.

I also found multiple such organizational routines and policies in the data I collected about the mortgage lending and appraisal industries. One example of an organizational policy common to both of these industries (though with distinct applications) is that of exercising discretion. Mortgage underwriters exercise discretion when evaluating prospective mortgage loan borrowers. And, since the first page of the Uniform Residential Loan Application (Form 1003) is not concealed for underwriter review, underwriters view loan applicant names, race/ethnicity, and sex information in addition to information about income and employment. Even if unintentionally or unconsciously, underwriters can evaluate otherwise qualified minority borrowers as high-risk and deny the loan through the exercise of discretion.

“for sale” by nathan esguerra is licensed under CC BY 2.0

In the appraisal industry, the rule of discretion in selecting ‘comps’ (comparable sales used as key data points to determine home value in the sales comparison approach to appraising) enabled appraisers to rely on widely shared stereotypes about Black and Hispanic neighborhoods as dangerous and undesirable and White areas as safe and desirable. Because they could exercise judgment in the areas from which they selected comps, they used these stereotypes to rationalize their decisions to avoid selecting comps for homes in White neighborhoods from Black or Hispanic neighborhoods and vice versa. This practice reinforces home value disparities across racially distinct neighborhoods.

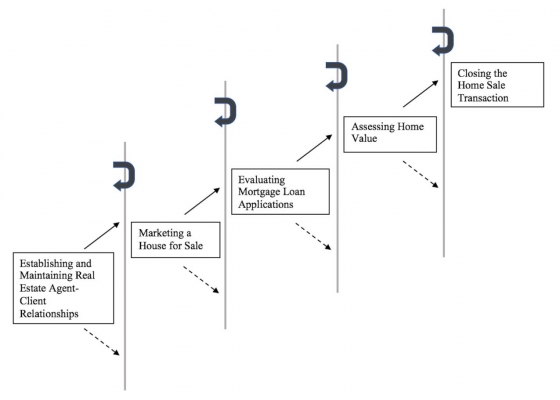

Second, I found that the stereotyping and discrimination supported by organizational routines and policies accumulated, or compounded, across the multiple stages of the housing exchange process. This accumulation occurred at both the individual and neighborhood level. That is, stereotyping and discrimination occurred across linked stages of interaction, exposing White individuals and neighborhoods and individuals and neighborhoods of color to multiple, related opportunities to experience inclusion or exclusion through the application of widely shared racial stereotypes. Figure 1 illustrates how this compounding inequality works.

Figure 1 – Compounding Inequality across the Stages of Housing Exchange

Note: Solid arrows indicate progressing to the next stage of exchange. Dashed arrows indicate exclusion from the next stage. Solid gray lines suggest crossing into successive stages. Bold U-turn arrows indicate a recycling of common-sense racial stereotypes as individuals cross into succeeding stages, thus affecting the conditions of their inclusion.

Consider the multiple steps involved in purchasing a home: by the time a buyer of color has reached the home sale closing—if not at some point categorically excluded from further participation—they have been repeatedly subjected to widely shared racial beliefs about their ability to care for homes, financial instability, knowledge of the homebuying process, potential for danger, and desirability as a neighbor. These instances of unequal treatment and outcomes accumulate across the stages of housing exchange. Meanwhile, White buyers have repeatedly been given the benefit of the doubt, experienced positive treatment because of assumptions about their income or wealth status, or even been given the inside track on non-public home sale listings because they are perceived as high-value, low-risk customers. Thus, housing inequality becomes durable not only because there are systematic differences in racial residential preferences and discrimination within each stage of the housing exchange, but also because these racial preferences and unconscious or conscious racial stereotypes affect how discrimination unfolds and compounds across the entire process.

The same kind of accumulating inequality can also happen for neighborhoods. As the housing exchange process unfolds, key housing market stakeholders categorically exclude neighborhoods, like individuals, at various points throughout successive stages or, if they do include them, may treat them in qualitatively distinct ways. For neighborhoods of color, the results can be devastating: a narrowed pool of competition for for-sale homes, the ongoing conflation of neighborhood racial and low-income status at the organizational level, less or lower-quality investment from banking institutions, and few opportunities, if any, to reduce systematic disparities in home values all accumulate across the serially linked stages of housing exchange to compound disadvantage. For white neighborhoods, the results are glowing: a broad pool of competition for for-sale homes, the ongoing conflation of neighborhood racial and high-income status, more and higher-quality investment from banking institutions, and the ongoing reinforcement of systematically higher home values interlock and compound advantage.

The results from my study also point to meaningful possibilities for policy intervention, specifically with respect to organizational routines and policies. For example, within mortgage lending and appraising, organizational leaders and policymakers can minimize discretion in interpreting mortgage loan applications and in selecting comps, respectively. Within real estate brokerage, industry leaders and policymakers can examine the potentially discriminatory effects of the (unofficial) percentage-based commission policy and implement alternate pay structures. These and other organizationally targeted interventions can more effectively reduce compounding housing inequality by de-incentivizing discriminatory behavior and reliance on racial stereotypes. In turn, these interventions could also reduce racial residential segregation and interrupt the ongoing inequalities that emerge from it.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Compounding Inequalities: How Racial Stereotypes and Discrimination Accumulate across the Stages of Housing Exchange’, in American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/31cLnyg

About the author

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn – University of New Mexico

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn – University of New Mexico

Elizabeth Korver-Glenn is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. Her research interests lie at the intersections of housing, segregation, race/ethnicity, and immigration. Previous work has been published in multiple scholarly journals, including the American Sociological Review, Social Currents, Qualitative Sociology, City & Community, and Sociology of Race and Ethnicity, as well as in industry outlets such as REALTOR® Magazine. To learn more about her work, visit her website.