In the contemporary US Senate the votes that count are those to end debate and to proceed with the motion at hand. In new research Carlos Algara and Joe Zamadics look at why some Senators break with their party and vote to end debate rather than sustain a filibuster. They find that when majority party Senators defect for such pivotal votes, this differentiates them among their constituents, helping them to do better in tough re-election races back home.

In the contemporary US Senate the votes that count are those to end debate and to proceed with the motion at hand. In new research Carlos Algara and Joe Zamadics look at why some Senators break with their party and vote to end debate rather than sustain a filibuster. They find that when majority party Senators defect for such pivotal votes, this differentiates them among their constituents, helping them to do better in tough re-election races back home.

On February 25th, 2019, the US Senate voted on cloture (to end debate) on the motion to proceed S. 311. Based on the banal rollcall vote title, the motion to proceed may seem like a trivial Senate matter, easily ignored by voters and the media. However, the result of the vote was far reaching for the Democrats that broke with their party on the bill.

S. 311 was a direct response to the Virginia Legislature’s move to lower restrictions on abortion. The stated purpose of the bill was “to amend title 18, United States Code, to prohibit a health care practitioner from failing to exercise the proper degree of care in the case of a child who survives an abortion or attempted abortion.” Republicans believed the bill would protect newborns, while most Democrats viewed the bill as a restriction on abortion.

The vote was not on the issue of abortion. The vote was to decide if there were 60 Senators present who approved ending debate on the bill. In the US Senate, 60 votes are needed to end the chambers “unlimited debate.” The vote ended with 53 Yeas, 44 Nays, and three not voting, meaning the bill failed by seven Yeas to move to a final vote. All Republicans present voted in favor of ending debate. Media coverage largely focused on the three Senators who broke with Democrats and voted to continue to the final passage vote: Bob Casey (PA), Doug Jones (AL), and Joe Manchin (WV).

Why would those three Senators break with their party on a procedural matter? In the House of Representatives, members seldom break with their party on procedural votes. In the Senate, the practice is common. Our recent work proposes a theory as to why those three broke with their party on a procedural matter.

Why Senate procedural votes are important

Unlike their counterparts in the US House, Senators are privileged with a greater degree of procedural rights that can be used to influence the legislative process. Moreover, to advance legislation to the floor, the Senate majority leadership must rely on the support of 60 Senators to invoke cloture and end debate on a given legislative proposal. Indeed, the 60-vote threshold in the Senate to overcome the legislative filibuster is often cited as the strongest veto point in the legislative process, with most legislation requiring a de facto 60 votes. However, if the Senate majority party can muster the 60 votes needed to invoke cloture, than final passage is foregone conclusion

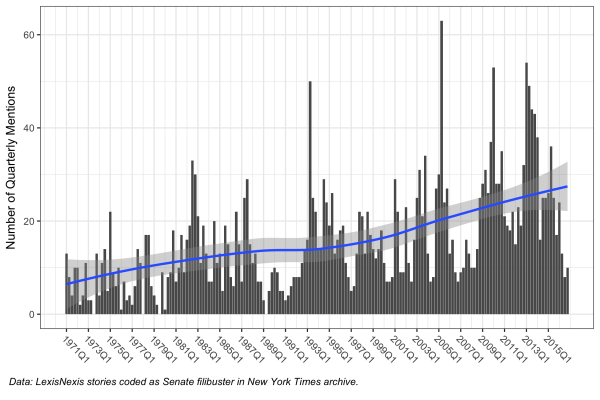

Scholars note that the contemporary Senate is one marred in procedural conflict, with the minority party increasingly voting as a cohesive bloc to prevent the majority party from invoking cloture on legislation it seeks to pass, thus successfully sustaining a filibuster. Indeed, this increase of legislative filibusters on the Senate floor has attracted the media’s attention. Figure 1 below shows this point by showing the increase of quarterly mentions of the Senate filibuster in the New York Times from 1971-2016.

Figure 1 – Quarterly New York Times mentions of Senate filibuster, 1971-2016

This growing importance of media coverage about the Senate filibuster is pivotal for two reasons. First, this increase in media coverage about the filibuster coincides with a dramatic increase in the proportion of the Senate legislative calendar dedicated to overcoming minority-led Senate filibusters. Second, the mass public is increasingly exposed to a portrait of the Senate as a legislative body marred in procedural conflict and perpetual gridlock. Indeed, the latter point is significant given that the mass public harbors negative views of legislative obstruction and gridlock.

Opportunity for defection: Anticipating electoral rewards

We argue that the increased attention given to procedural votes in the Senate provides Senators with a unique opportunity to differentiate themselves on the Senate floor. Scholars have long remarked that Senate procedural votes, unlike those in the House, garner large amounts of media attention. Given that successfully invoking of cloture makes a final passage vote largely symbolic in the Senate, procedural votes are largely treated as the pivotal in the legislative process.

We argue that the dynamics surrounding procedural votes provides Senators with a major opportunity to differentiate themselves from their party towards an electoral gain. Specifically, we argue that Senators may be cross-pressured between serving the party’s procedural goals and the policy preferences of their constituents. For majority party Senators representing states with a partisan preference for the minority party, this suggests that they may reap an electoral reward if they vote against party leadership on procedural votes. For minority party Senators representing states with a partisan preference for the majority party, this suggests an electoral reward if they vote against their party and with the majority to advance legislation.

Credit: FEMA/Bill Kolitz.

The implication of the propositions above is that Senators are aware of the importance of procedural votes and anticipate an electoral penalty if they vote with their party ahead of their constituents. We test this proposition using a new measure of Senator preference on procedural votes from 1971-2016 and find that Senators moderate their procedural preferences ahead of a re-election bid conditional on the partisan preferences of their constituents.

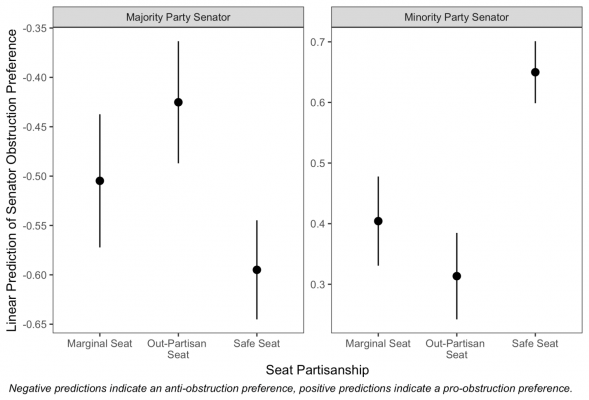

Figure 2 – Interactive effect of majority status and seat partisanship on obstruction preference

Deriving electoral benefits by defecting from their party

We find evidence that majority party Senators representing states dominated by the minority partisans to exhibit more “pro-obstruction” preferences than their colleagues representing partisan safe seats. By contrast, we find that minority party Senators representing majority party dominated states exhibit more “anti-obstruction” preferences than their safer-seat colleagues. Since Senators anticipate an electoral consequence for their procedural voting record, we explore the extent to which they reap electoral rewards from their procedural voting records. Figure 3 below shows the extent to which minority and majority party Senators gain electorally on the basis of their obstruction voting record and the type of state they represent.

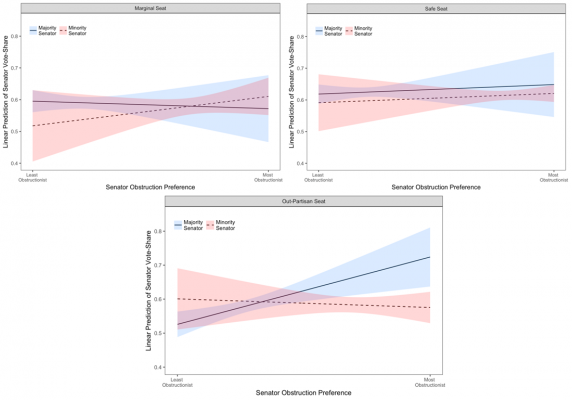

Figure 3 – Interactive effect of obstruction, majority, and partisanship on Senate vote-share

As the figure shows, only majority party Senators representing states dominated by minority partisans gain electoral support from their obstruction preference behavior. The more obstructionist in their preference, the more these Senators stand to gain electorally. We contend this is due to the fact that majority Senators have a particularly good opportunity to differentiate themselves, since their votes are pivotal if Senate majority leadership wishes to advance its agenda through the chamber. Indeed, prominent theories of legislative organization in the Senate contend that the majority party cannot afford significant defections from rank-and-file members on procedural votes, given that final passage votes are conditional on successful passage of procedural motions.

Tying our findings to the abortion case

Our findings shed light on how procedural votes impact the strategic calculus of Senators and their re-election prospects. To that end, we are not surprised that Democratic Senators Joe Manchin, Doug Jones, and Bob Casey defected from minority Senate Democrats and voted with majority Republicans to end debate on the abortion bill before the Senate. With two of these Democratic Senators representing strongly Republican states, it is rational to act on electoral incentives on procedural votes. We hope our work provides a framework for future inquiry into the nature of procedural votes in the contemporary Senate.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘The Member-Level Determinants and Consequences of Party Legislative Obstruction in the U.S. Senate’ in American Politics Research.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ChBLYg

About the authors

Carlos Algara – University of California, Davis

Carlos Algara – University of California, Davis

Carlos Algara is a doctoral candidate in political science at the University of California, Davis. His research focuses on the nature of legislative representation and behavior, the electoral process, mass public opinion, and latent variable measurement methods. His website can be found at: https://calgara.github.io.

Joseph C. Zamadics – University of Colorado Boulder

Joseph C. Zamadics – University of Colorado Boulder

Joseph C. Zamadics is currently a PhD candidate at the University of Colorado Boulder. His current research uses content analysis to measure issue salience at the local level to develop richer theories of lawmaker response to large events. Other areas of research include state legislatures, Congress, and legislative success.