Social media and other online innovations allow city managers to engage with their citizenry in new – and often relatively inexpensive – ways. But why have some cities embraced and adopted these technologies while others have lagged behind? In new research which draws on a survey of 2,500 managers in 500 cities, Fengxiu Zhang and Mary K. Feeney find that such engagement tends to occur when managers believe that citizen participation is important, necessary, and beneficial, and they feel that their agency has a high level of need to engage more with the public.

Social media and other online innovations allow city managers to engage with their citizenry in new – and often relatively inexpensive – ways. But why have some cities embraced and adopted these technologies while others have lagged behind? In new research which draws on a survey of 2,500 managers in 500 cities, Fengxiu Zhang and Mary K. Feeney find that such engagement tends to occur when managers believe that citizen participation is important, necessary, and beneficial, and they feel that their agency has a high level of need to engage more with the public.

Government managers have long struggled with the challenge of civic engagement. Some argue that new communication technologies, such as social media, web portals and online interactive platforms, are the key to improving how cities engage with their citizens.

Technologies known for their low-cost, ubiquity and ease-of-use provide governments with the opportunity and ability to reach more communities and interact with them in innovative ways. Examples of cities utilizing technology to foster local participation abound. For instance, Austin, Texas created an online program to engage public housing residents. Raleigh, North Carolina developed an online tool that makes it easier for the public to get involved in government planning.

However, not all cities fully embrace the vision and potential of these tools. Years after social media technologies have become widely available, we continue to see cities and managers not using them in civic engagement processes. Some cities do not adopt these technologies, and when they do, managers do not use them to engage the public in dialogue.

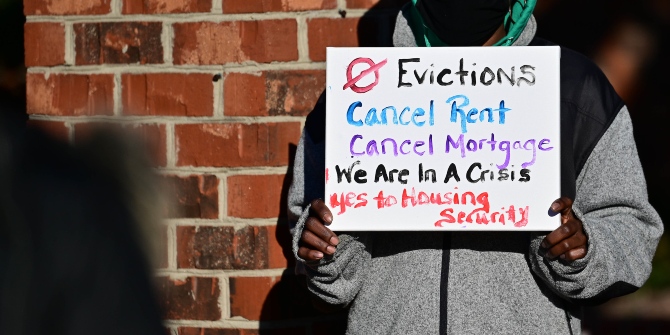

Photo by Joey Kyber on Unsplash

Technology offers potential – but what triggers its use for civic engagement? To understand technology use for civic engagement, we need to consider the role of public managers. Because managers are responsible for designing and executing public participation, we suggest that how they view civic engagement matters for technology adoption and use. Our research draws from a 2014 national survey of 2500 managers from a representative sample of 500 US cities with populations of 25,000 to 250,000 conducted by the Center for Science, Technology and Environmental Studies (CSTEPS) at Arizona State University. Included in the final analysis are responses from 767 managers in 400 cities.

How do managers view public participation?

Public managers’ views on civic participation are two-fold: their beliefs about and their perceived needs for participation. On the one hand, there has been a great deal of discussion on the benefits of participation, such as improving government decision making, increasing policy legitimacy and enhancing citizen trust; how much managers subscribe to those values reflects their beliefs about participation. On the other, the benefits of participation do not come without costs. Civic engagement requires managers to spend extra time and resources to educate the public on government issues and solicit their input. Many managers find themselves unable to deal with public input. The increased costs and lack of capacity can reduce managers perceived needs for including participation in their work. After all, if public input is costly to obtain and difficult to use, would public managers perceive a need to increase civic engagement?

Our survey data suggest that managerial beliefs about and perceived needs for participation do not align. Figure 1 shows the percentage of managers that agree or disagree that: 1) Governments need to fully integrate citizens in decision processes; 2) citizen participation increases government effectiveness; and 3) Citizen participation is necessary even when it dramatically slows down government decisions.

Figure 1 – Managerial beliefs about citizen participation

Note: Maroon bar: agreement, Gold bar: disagreement

Figure 2 shows that if managers think the current level of citizen participation is too much or too little with regard to employee conduct, department management, department decisions, service feedback, service priorities, and long-range plans. The figures show that while managers overwhelmingly hold positive beliefs about citizen participation, fewer of them perceive a need for their agency to increase participation.

Figure 2 – Manager perceived needs for citizen participation

Note: Maroon bar: Current participation is too little, Gold bar: Current participation is too much

How do public managers matter?

To understand how managerial views of public participation affect technology adoption for civic engagement, we coded city website portals for web features related to technology for civic engagement, including having a mayor’s blog, contact information for the mayor, city council agenda, Facebook link, Twitter link, YouTube link, voter registration forms, voter information, and Freedom of Information Act request options. We used the total number of engagement tools to measure the level of technology adoption in each city as related to manager beliefs and needs for participation.

Figure 3 shows the relationship between managers’ beliefs about and perceived needs on technology adoption. The red, blue, and green lines show the influence of manager beliefs on technology adoption when managers perceived low, medium, and high levels of needs for participation, respectively. The solid lines indicate statistically significant evidence for the relationship and the dotted line indicates lack of evidence. The upward slopes of the green and blue lines suggest that managerial beliefs are related to higher levels of technology adoption; the steeper the lines, the stronger the relationship.

Figure 3 – Effect of manager views on technology adoption

Note: Solid lines: Statistically significant relationships, Dotted lines: Not statistically significant

Figure 3 shows that when managers believe that participation is important, necessary, and beneficial while not thinking the current participation is too much, they adopt more technology to foster civic engagement (see the blue line). When managers perceive high levels of needs for participation in their agency, they tend to adopt even more technology tools to facilitate citizen engagement (see the green line). Finally, while it is reasonable to expect managers perceiving low needs for participation in their agency to reduce technology adoption, our study does not find such evidence (see the dotted red line).

What can the public and governments do?

Our study underscores the important role of managerial beliefs in promoting government adoption of technology for civic engagement. Participation advocates, including lobbyists, stakeholder groups, and concerned citizens, can advance civic engagement by focusing their efforts to capitalize on managers’ positive beliefs about participation. Governments that wish to fully unlock technology potential for civic engagement can adjust their hiring practices or devise communication and education strategies to influence managerial beliefs about civic engagement. Positive examples of how citizen participation has advanced government decision-making and outcomes should be included in efforts to enhance managers’ positive views of civic engagement. Government can also take steps to boost managerial capacity to make participation more manageable and desirable, such that technology adoption for civic engagement can be further reinforced.

- This article is based on the paper, ‘Managerial Ambivalence and Electronic Civic Engagement: The Role of Public Manager Beliefs and Perceived Needs’ in Public Administration Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics, nor the authors’ institutions.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2ia0tCN

_________________________________

About the authors

Fengxiu Zhang – Arizona State University

Fengxiu Zhang – Arizona State University

Fengxiu Zhang is a PhD student and Graduate Research Assistant at the Center for Science, Technology, and Environmental Policy Studies at Arizona State University. She is interested in decision making under risk and uncertainty, civic engagement and crisis management. She is currently working on research investigating public organization adaptation to extreme events and technology use in local governments.

Mary K. Feeney – Arizona State University

Mary K. Feeney – Arizona State University

Mary K. Feeney is Associate Professor and Lincoln Professor of Public Affairs at Arizona State University. She is interested in public and nonprofit management, sector distinctions, and science and technology policy. She is currently working on research investigating technology use in local governments and mentoring in ST&E fields.