What influences Congress into passing certain reforms when it does? To investigate this question, Logan Strother looks at two reforms to the National Flood Insurance Program: the first drastically reduced or eliminated flood insurance subsidies, while the second only two years later restored them. He argues that Congress effectively reversed course because the passage of the first reform made the issue much more important to voters than it had been before. While Congress had previously been able to act with a relatively free hand, once voters became interested, legislators had incentive to undo their own reforms.

What influences Congress into passing certain reforms when it does? To investigate this question, Logan Strother looks at two reforms to the National Flood Insurance Program: the first drastically reduced or eliminated flood insurance subsidies, while the second only two years later restored them. He argues that Congress effectively reversed course because the passage of the first reform made the issue much more important to voters than it had been before. While Congress had previously been able to act with a relatively free hand, once voters became interested, legislators had incentive to undo their own reforms.

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) has a unique history of failure dating back to its origins in the 1960s, but the massive disaster ushered in by Hurricane Katrina in 2005 made the program’s greatest failures too clear to ignore. Years of input by policy experts in insurance and flood mitigation ultimately led members of Congress to consider a bundle of major policy reforms that would shift the burden of flood risk onto the people, businesses, and communities that choose to live and work in areas at high risk of flooding. These particular reforms reflected the lessons learned by some fifty years of policy failures; by-and-large, these failures were attributable to the Program’s emphasis on providing affordable insurance instead of on deterring development of flood-prone areas. In 2012, Congress passed the Biggert-Waters Act, which sought to drastically reduce or eliminate flood insurance subsidies for most properties, increase flood insurance market penetration, address the problems of repetitive- and severe-repetitive-loss properties, among other things. In short, Biggert-Waters aimed to remedy some of the greatest failures of the National Flood Insurance Program.

Biggert-Waters was supported by large majorities of each party, was passed by overwhelming margins in both houses of Congress, and was signed into law by President Obama on July 6th of 2012. However, this landmark effort at genuine public-interest reform was short-lived. The Grimm-Waters Act of 2014 (also known as the “Homeowner Flood Insurance Affordability Act of 2014”), was designed explicitly to gut most of the policy reforms embodied in Biggert-Waters: it restored subsidies for most types of properties, reinstated a grandfather clause for flood insurance requirements, and otherwise restored the pre-Biggert-Waters status quo. It is notable also that Grimm-Waters passed by large, bipartisan margins similar to those Biggert-Waters. This rapid about-face by Congress is puzzling: why would large majorities of Congress support a major public-interest reform measure only to dismantle it less than two years later? It is important to note that this is not a simple story of a newly elected Congress undoing some of the work of its predecessor: most of the members of Congress who voted for Grimm-Waters also voted for Biggert-Waters.

Political scientists have long noted the tendency for interest groups to be far more successful than the public at large when it comes to securing benefits from policies. For this reason, bona fide general interest reforms, which benefit the public at large rather than particular groups, are typically viewed as deviations from the norm. Because of the incentives that elected officials face, general interest reforms, rare as they are to begin with, are thought to be especially susceptible to retrenchment. In one famous study of general interest reforms, Eric Patashnik argues that major reform measures are typically passed in moments of salience—intense political interest—and then often die the “slow death of a thousand nicks” where the slowness of the death provides the cover behind which interest groups are able to obscure the actions from the public.

These classic accounts, however, don’t seem to explain what we witnessed in the area of flood insurance policy after Hurricane Katrina. In recent work, I examined the history of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) with particular focus on its recent development, and found that the major general interest reform measure, the Biggert-Waters Act, was passed with virtually no pressure or even attention from the public—a clear departure from the accepted model. Additionally, I found that after Biggert-Waters was passed and the policy changes began to be implemented, Biggert-Waters became salient—and was rapidly dismantled by Congress. In other words, the politics of NFIP reform from 2005-2014 appear to invert the usual story of policy reform and retrenchment.

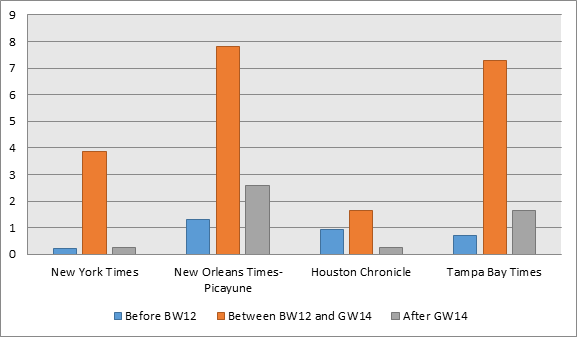

A key piece of this puzzle, I contend, is the effect of policy attention on the incentives of members of Congress. Bureaucrats and members of Congress were able to pass the reform measure in relative obscurity, but the passage of the bill and the new reality of rising premiums it portended caused the issue to become much more salient than it had been. I gathered data from four major newspapers in states that have relatively high NFIP market penetration—which is to say, the sorts of the places where readers are particularly likely to be affected by the reform measures. The figure below presents the average daily number of newspaper stories covering the National Flood Insurance Program while reforms were being considered in Congress (“Before BW12”), after Biggert-Waters was passed (“Between BW12 and GW14”), and after the reforms were gutted in Grimm-Waters. The figure clearly indicates that the passage of Biggert-Waters made the National Flood Insurance Program salient. In short form, people who were negatively affected by the new policy (i.e. faced rising premiums, and in some cases, falling property values), became acutely aware of the National Flood Insurance Program and demanded Congress “fix” the rate hikes.

Figure 1 – Average Daily Number of Media Stories on NFIP

Note: The figure depicts the average daily number of stories in each newspaper. Keywords searched were “National Flood Insurance Program,” “National Flood insurance reform,” “Biggert-Waters,” and “Grimm-Waters.” The series labeled “Before BW12” includes the period from August of 2008 until the passage of Biggert-Waters in July 2012; the series labeled “Between BW12 and GW14” includes the period bounded by the day each measure was signed into law; the series labeled “After GW14” includes the 12-month period after Grimm-Waters was enacted.

The massive increase in public attention to NFIP, I argue, significantly influenced the incentives of sitting members of Congress. Faced with angry constituents, Congress shifted away from working for general interest reform and toward securing their own reelection, and did so by eviscerating the offending legislation. A couple of examples of pre-vote rhetoric by members of Congress illustrate the change of heart. Before the vote on Biggert-Waters, Senator Carl Levin (D-MI) noted that [Biggert-Waters] “require[s] that premiums be more reflective of the true risk of flooding. The conference report will phase out subsidies for repetitive-loss properties that continue to be rebuilt in high-risk areas. It will also phase out subsidized rates for vacation homes and businesses located in high-risk areas, many of which have received subsidized rates for more than 30 years.” Close examination of the Congressional record shows that the emphasis of the floor debate on Biggert-Waters was clearly on requiring people and businesses in flood-prone areas to pay actuarially sound rates. After NFIP became important —and Biggert-Waters became unpopular, in particular—members of Congress changed their tune.

Senator Bob Menendez (D-NJ) urged passage of the Grimm-Waters Act during debate, contending that it was necessary to “prevent sky-rocketing rate increases” by creating an annual rate-increase firewall and reinstating the grandfathering of properties, among other things. “It has something that I thought was critically important…an affordability goal.” Indeed, affordability, rather than necessary reform or actuarial soundness, dominated the Congressional debates over Grimm-Waters. And it is notable that members of Congress were basically successful in protecting themselves: after gutting the Biggert-Waters reform package and thus alleviating the threat to their constituents, NFIP salience quickly fell back to pre-Biggert-Waters levels, as the figure illustrates.

My findings indicate that major policy reform does not always come in rare moments of policy salience, and retrenchment does not always come in obscurity. These findings suggest that the political context of a policy domain has important implications for both reform and retrenchment: obscure, technocratic policies (policies “without publics”) can be reformed without much need for public attention. In order to understand the politics of policy reform and retrenchment, we must pay attention to the presence (or absence) of public attention. When issues aren’t important to the public, technocrats and interested members of Congress can create policy with a relatively free hand; when policies are (or become) salient, however, policy choices will be constrained by those publics. The upshot of this is that scholars of the policy process should attend to differences in policy making processes across political contexts, rather than search for universal tendencies.

This article is based on the paper “The National Flood Insurance Program: A Case Study in Policy Failure, Reform, and Retrenchment,” in the Policy Studies Journal.

Featured image credit: DVIDSHUB (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2iAueL9

_________________________________

Logan Strother – Syracuse University

Logan Strother – Syracuse University

Logan Strother is a Ph.D. candidate in political science at Syracuse University’s Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs, and Visiting Scholar at the Harry S Truman School of Public Affairs at the University of Missouri. His research, which is focused on the intersections of public law and public policy, has been published in the Journal of Law and Courts and the Policy Studies Journal, among others.