In recent decades, the dominant narrative of Detroit has been one of decline. Paul Draus and Juliette Roddy write that this conceit has also become associated with the metaphor of monstrosity which shows the Motor City as a kind of urban nightmare. They write that while some of Detroit’s proponents have embraced this narrative, others have sought to reframe it as one where the city has been preyed on by federal and state neglect. By giving a greater voice to Detroit’s residents, they hope to challenge the city’s ongoing trope of decline.

In recent decades, the dominant narrative of Detroit has been one of decline. Paul Draus and Juliette Roddy write that this conceit has also become associated with the metaphor of monstrosity which shows the Motor City as a kind of urban nightmare. They write that while some of Detroit’s proponents have embraced this narrative, others have sought to reframe it as one where the city has been preyed on by federal and state neglect. By giving a greater voice to Detroit’s residents, they hope to challenge the city’s ongoing trope of decline.

Like other ghost stories, the tale of Detroit’s fall is one that people never seem to get tired of telling. Popular accounts of the city focus not only on what has been lost, but also what cannot be buried: they are equally about the city’s past and its failure to leave it behind or put it at peace. Documentary films such as Requiem for Detroit (2010), Deforce (2010), and Detropia (2012) represent variations on this theme: all depict a city full of abandoned buildings, effectively sacrificed on the altars of suburban sprawl and globalization. Frequently invoked are historic policies which are retrospectively viewed as collective sins or crimes, especially that of racial segregation. The withering of the welfare state and the starving of municipal governments are reflected in the eroding structures that one confronts in the physical landscape of the city. While Detroit’s ruins have become a destination for urban explorers, they remind long-term residents of both its precipitous plummet and its bedraggled present status.

It wasn’t always this way. Detroit was a boomtown in the early 20th century, an embodiment of optimistic modernism. Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry murals, still on glorious display at the Detroit Institute of Arts, are a paean to this muscular make-it-happen spirit. This image of Detroit persists today, though primarily in the form of nostalgia for its long-lost golden era.

Physical traces are visible in the early to mid-20th century modernist architecture that still stands in Detroit. Some buildings, such as the Fisher Building in the New Center area, have remained in use, and others have been rehabilitated, such as the Fox Theater and the Guardian Building. These structures are lingering testaments to the times in which they were constructed.

Since at least the late 1960s, however, Detroit’s dominant narrative has been that of decline. For some observers, the city’s very atmosphere seems to collaborate in the outcome, in spite of all good intentions. Ze’ev Chafets’ 1990 book Devil’s Night and Other True Tales of Detroit set the tone for what has now become a journalistic subgenre. In a 2004 article in Playboy called Detroit Death City,” Frank Owen called Detroit “a throwaway city for a throwaway society, the place where the American Dream came to die”. For local journalist Charlie LeDuff in 2013, Detroit was already terminal, necessitating an autopsy.

While it continues to lose full-time residents, however, the city of Detroit still attracts observers and monstrous metaphors by the scores. From the haunted faces of abandoned homes and factories, to the threatening images of crack and heroin users prowling the streets like armies of undead, themselves the victims of parasitic street pharmacists; from the unidentified bodies frozen in ice or dismembered and dumped into empty fields; to the men living half-wild in the overgrown interiors of once-dense neighborhoods, and the lions let loose in abandoned factories, Detroit seems to invite sensationalist story-telling.

Detroit’s status as archetypal urban nightmare was solidified by Hollywood movies such as Robocop (1987) and The Crow (1994), which utilized dystopian images of a city overrun by murderous thugs as a backdrop for their revenge fantasies. Though not shot in the city, these films were deliberately set in Detroit, a backdrop which inevitably cues the American racial imaginary, as does the perennial association of central cities with anonymous forces of darkness. It may also go without saying that the resurrected heroes in both films are White—in the case of The Crow, chalk-white (albeit with a lot of black eyeliner).

Some of the city’s boosters have embraced this badass image, erecting Robocop statues, hawking t-shirts emblazoned with belligerent slogans such as “Detroit: Where the Weak Are Killed and Eaten,” or “Detroit Vs. Everybody.” (Others reference it implicitly: “Say Nice Things About Detroit,” or “Detroit Hustles Harder.”) The Marche du Nain Rouge is a recently created Mardi Gras-wannabe-festival based on the legend of a malevolent imp who appears in advance of each major crisis, most notably before the 1967 police riot/popular rebellion that gutted much of the city’s commercial core. It takes place in the heart of Detroit’s most infamous vice district, the Cass Corridor; its intent is to expurgate these evil spirits, even as it celebrates their vitality. For some, the city’s emergence from municipal bankruptcy in late 2014 represents a new start, a chance to wipe the slate clean of both the debts and the sins of the past.

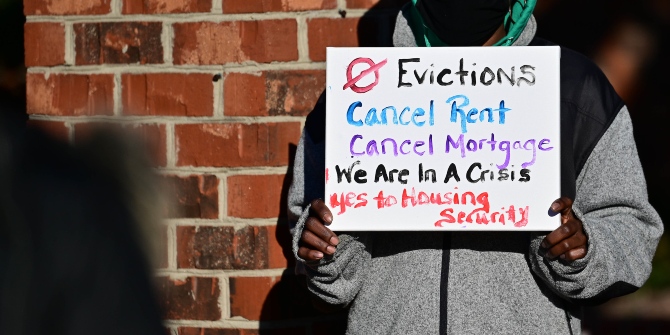

Others are more critical. The work of Tim Burke, displayed at his Detroit Industrial Gallery on Heidelberg Street, utilizes commercial signs, salvaged items and found objects, re-contextualized to promote dialogue on the role of the federal and state governments in systematically producing Detroit’s devastation through discriminatory housing policy, punitive welfare policy, and the carceral state. The real monster here is not the city, or its residents, but those who have preyed upon them.

As researchers in Detroit, engaging in ethnographic interviews with residents has provided a thorough education in the history of racial segregation and economic disinvestment that have so powerfully shaped the landscape people live in today. Our conversations have yielded descriptions of the city as a “death trap”, a “ghost town”, and a “post-apocalyptic” environment. When hearing statements such as these, it is tempting to view the problems of Detroit as a magnification of societal ills. Instead, we strive to focus on what is actually happening on the ground, in the muddier terrain of lived social reality.

In the documentary We Are Not Ghosts (2012), Detroiters challenge the trope of decline through their creativity and persistence. In Detroit, this struggle takes place every day at the level of lots and yards and blocks. Artists embellish the landscape with repurposed castoffs; neighbors collaborate to cut lawns and cultivate gardens; throngs of bicycles reclaim streets in the Detroit Slow Roll. As one pastor said to us, in the course of our research: “You have to eat the monster one bite at a time.”

This article is based on the paper, ‘Ghosts, Devils, and the Undead City: Detroit and the Narrative of Monstrosity’ in space and culture.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1QYRbBc

_________________________________

Paul Draus – The University of Michigan-Dearborn

Paul Draus – The University of Michigan-Dearborn

Paul Draus is Director of Public Administration, Director of Public Policy, and Associate Professor of Sociology at The University of Michigan-Dearborn.

Juliette Roddy – The University of Michigan-Dearborn

Juliette Roddy – The University of Michigan-Dearborn

Dr. Juliette Roddy is an economist with research that is focused on the Detroit Metropolitan area. Her current projects focus on rational behavior and individual response to policy. She partners with a variety of community agencies including Detroit Health and Wellness Promotion, investigating the economic effects of interventions on individual behavior and health.