Past research has shown that the political participation of minorities in America is influenced by where they live and work, but few have tested exactly what drives this relationship. In new research, Brittany N. Perry and Christopher D. DeSante assess one possible mechanism: the effect of co-ethnic population size on the acquisition of political knowledge. They find that ethnic context helps condition how people acquire knowledge among people in the same ethnic group, which in turn, affects political engagement. Focusing on Latinos, this study shows that as Latino population size in a county increases, political knowledge and interest levels among Latinos increase, and importantly, political information and interest gaps between citizen and non-citizens decrease considerably.

Past research has shown that the political participation of minorities in America is influenced by where they live and work, but few have tested exactly what drives this relationship. In new research, Brittany N. Perry and Christopher D. DeSante assess one possible mechanism: the effect of co-ethnic population size on the acquisition of political knowledge. They find that ethnic context helps condition how people acquire knowledge among people in the same ethnic group, which in turn, affects political engagement. Focusing on Latinos, this study shows that as Latino population size in a county increases, political knowledge and interest levels among Latinos increase, and importantly, political information and interest gaps between citizen and non-citizens decrease considerably.

Does the context in which people live affect how much they know about politics? While it is not new to political science, work on the effects of context and geography on political behavior has become more common. Extensive research has shown that individual-level traits affect political engagement, i.e. those residents who are older, wealthier, better educated or are citizens are far more likely to be politically active. But scholars have also considered how one’s environment figures into the participation equation. While many have found evidence showing that certain kinds of context matter (information or media market, homogeneity of neighborhood, etc.), few have directly tested the interaction between contextual and individual-level variables and how these interactions drive behavior. This new research presents a first step in this process by assessing how context affects the acquisition of political knowledge.

In this project, we investigate how context affects knowledge rates among a particular group in the U.S.: Latinos. Our analysis shows that increases in co-ethnic (Latino) population size decrease political knowledge gaps between citizen and non-citizen Latinos in a given place. The primary implication is that contextual changes in American communities may be reducing barriers and costs to political knowledge acquisition, which may, in turn, trigger higher Latino citizen turnout rates and higher non-citizen engagement in non-electoral politics, including registration and get-out-the-vote drives.

Theoretically, it is important to consider context in the study of political engagement, as the place in which one lives conditions access to resources and social groups that aid in the development of civic skills. Particularly for groups with lower levels of English proficiency and less experience in the United States, including non-citizen Latinos, context can either facilitate or hinder political knowledge acquisition. In areas with more co-ethnics (Latinos), we claim that non-citizens will have greater access to Spanish-language media and Latino-dominated churches and civic groups, which have been shown to facilitate political interest and activity. Thus our primary argument is that while all Latinos will benefit from increases in co-ethnic population size in their counties, non-citizens will benefit to a greater degree.

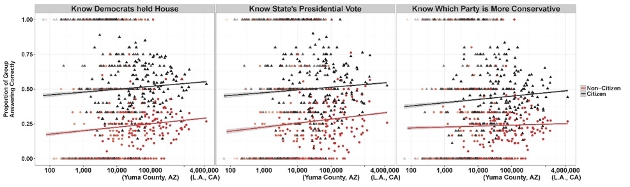

Using a restricted version of the 2006 Latino National Survey (which contains respondents’ federal information processing standard (FIPS) codes) and county-level estimates of Latino/Hispanic population size, we show that both citizenship and Hispanic population size are positively related to political knowledge. Below, Figure 1 suggests that citizen Latinos are more likely than non-citizen Latinos to know which party controls the House of Representatives (Democrats in 2006), which presidential candidate won in their state in 2004 (Bush or Kerry), and which party is more conservative when compared to non-citizens. It also seems that for both citizens and non-citizens, co-ethnic population size increases levels of political knowledge.

Figure 1 – Citizen and non-citizen Latino’s political knowledge

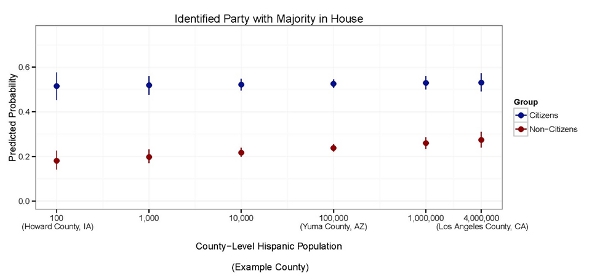

Moving beyond the raw data, we were able to show that knowledge and interest gaps between citizen and non-citizen Latinos decrease significantly as Latino population in a county increases. Figure 2, below, presents the predicted probabilities of a respondent correctly identifying the party which controlled the House in 2006. What we see is that those areas that have larger numbers of Latinos, such as in Los Angeles County, see diminishing differences between citizens and non-citizens, and gains in knowledge are being made disproportionately by the non-citizen population. The results are similar for additional knowledge measures and for levels of political interest.

Figure 2 – Citizen and non-citizen Latino’s political knowledge and Latino population size

These results are important for the future of American politics. Within the past 10 to 15 years, the Latino population, and specifically, the non-citizen subpopulation, has grown substantially. With this growth in population, especially concentrated growth in specific regions, we expect both citizens and non-citizens to have increasing access to political information, as organizations and the media market will respond to their rising demands. As these individuals become more informed and active, politicians will also respond and alter their strategy and policy production accordingly. To date, we have already seen changes on this front, as topics such as immigration reform, a particular concern for non-citizens in America, have recently made their way onto the national agenda. In addition, many state politicians, especially Republicans, have sought to modify their strategies to appeal to Hispanic voters. These individuals have already made a significant impact on electoral outcomes in many key, battleground states and will continue to do so, perhaps to an even greater degree, in the near future.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Bridging the Gap: How Geographic Context Affects Political Knowledge Among Citizen and Non-Citizen Latinos’, in American Politics Research.

Featured image credit: Sebastien Wiertz (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USAPP – American Politics and Policy, nor the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1OQ8zaf

_________________________________

Brittany N. Perry – Texas A&M University

Brittany N. Perry – Texas A&M University

Brittany Perry is an Instructional Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at Texas A&M University. Her research interests include racial politics in the U.S., the evolution of congressional institutions, Latino political representation, Latino immigration, and the effects of geography on political attitudes and participation rates.

Christopher D. DeSante – Indiana University

Christopher D. DeSante – Indiana University

Christopher DeSante is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Political Science at the Indiana University. His research is on race and racism in America, American political partisanship and political methodology.

[…] By Brittany N. Perry and Christopher D. DeSante, London School of Economics and Political Science […]