Recent weeks and months have seen rising fears about the spread of Ebola in the U.S. But the available evidence suggests that this is very unlikely. Why, then to people continue to be concerned? Joseph M. Parent and Joseph E. Uscinski look at the role that conspiratorial beliefs have played in people’s fears about Ebola. They write that for many, the Ebola outbreak is confirmation of conspiracy theories already held – that it is part of an Obama plot to ‘humble U.S. power or cancel elections, or that the pharmaceutical companies are somehow responsible. These beliefs are interacting with people’s partisanship and historical experiences to produce more fear about Ebola among large parts of the population.

Recent weeks and months have seen rising fears about the spread of Ebola in the U.S. But the available evidence suggests that this is very unlikely. Why, then to people continue to be concerned? Joseph M. Parent and Joseph E. Uscinski look at the role that conspiratorial beliefs have played in people’s fears about Ebola. They write that for many, the Ebola outbreak is confirmation of conspiracy theories already held – that it is part of an Obama plot to ‘humble U.S. power or cancel elections, or that the pharmaceutical companies are somehow responsible. These beliefs are interacting with people’s partisanship and historical experiences to produce more fear about Ebola among large parts of the population.

The odds of a serious Ebola outbreak in the United States are very low. This has not stopped Americans from fearing the worst. A recent national poll showed that almost fifty percent of the county believes the government is concealing important information about Ebola. From there opinions differ. Some suggest that Ebola is a part of an Obama plot to humble American power or to cancel this week’s midterm elections. Others think Ebola is population control scheme. Still others contend that big pharmaceutical companies created Ebola to reap profits by selling a cure. Threats are supposed to unify people, yet U.S. citizens seem split on whether Ebola is part of a conspiracy or not, and if it is a conspiracy who is behind it. Why?

Available information is an obvious place to start. Ebola is unquestionably a frightening disease. With no known cure and seventy percent mortality rate, fatalities are already high and likely to run much higher in Africa. Such lethal outbreaks are rare and that surely accounts for much of the attention and apprehension that has greeted Ebola. Yet does that not explain the diversity of anxieties and conspiratorial rhetoric surrounding the epidemic. On meager evidence, a host of political and corporate actors have been accused of atrocious actions.

Partisan predispositions play a large part. Whatever one thought was going on in the world before, the Ebola outbreak is resonant evidence to support one’s prior positions. Note how familiar many of these conspiracy theories’ charges are. Lots of Americans have accused Barack Obama of being insufficiently patriotic at every point in his career: he would not wear a flag pin, he did not spend enough on defense, his reluctance to use force signaled weakness to friends and foes. It should come as no surprise then that the President has been accused of purposely spreading Ebola in the US to “bring America down.” There has always been a small contingent of Americans who believe the (insert name here) Administration is going to cancel the upcoming elections and subvert democracy. News of Ebola has simply activated the same people to express the same fears. So, too, there is a recurrent motif in all sorts of conspiracy theories that powerful groups (like the infamous “New World Order”) want to enact draconian population control measures. And Ebola is another damning case for the many Americans who think that big business is out to get them: making vaccines that cause autism, dangerously modifying our agriculture, and contaminating our water. New facts constantly come in, but our conclusions seldom change.

Ebola virus Credit: CDC Global (Flickr, CC-BY-2.0)

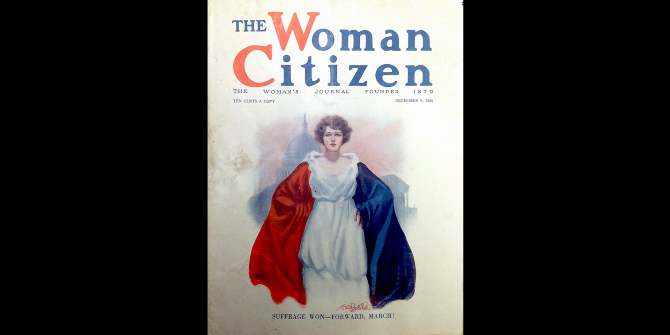

History contributes as well. A Fox News poll showed massive disparities in how blacks and whites view the threat posed by Ebola, with blacks being far more concerned than whites. With a historical worldview tainted by the Tuskegee experiments and a disproportionate number of AIDS victims, it is understandable that blacks would be uneasy with the spread of a virus. And blacks are only the most prominent group with reasons to be wary of the U.S. government. Veterans of Vietnam and the Iraq War claim they were exposed to harmful chemicals during their service.

Finally, conspiratorial predispositions are a part of us all, to a greater or lesser degree. Our research has found that, independent of party ties, some people are simply more likely to see events as the product of powerful groups plotting in secret. For example, take the monthly jobs numbers put out by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). A person with a non-conspiratorial worldview might see the frequently amended BLS numbers as a sign that accurate data is hard to collect and approves of revising figures in light of later, better information. A person with a strongly conspiratorial worldview might view the BLS as a puppet for the administration and its data as fabricated. Reponses to Ebola are no different.

Of course, information, partisanship, history, and conspiratorial predispositions all interact to produce the alarm we are now witnessing. And this may not be a bad thing. With so much scrutiny surrounding Ebola, any conspiracy afoot will likely be ferreted out. But even if nothing incriminating is found and these conspiracy theories peter out—as the vast majority of them do—history suggests that will not dent the popularity of conspiracy theories in general. Like kings, the death of some conspiracy theories only puts others on the throne.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1GH8PnP

_________________________________

Joseph Parent – University of Miami

Joseph Parent – University of Miami

Joseph Parent is an assistant professor of political science at University of Miami. His research interests include International Relations, American Foreign Policy, Political Integration, and Security Studies. He is the co-author of American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford University Press, 2014).

_

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joseph E. Uscinski – University of Miami

Joe Uscinski is associate professor of political science at University of Miami. He is the co-author of American Conspiracy Theories (Oxford University Press, 2014).