Housing assistance in the United States is unusual: unlike many other forms of public assistance, it is not an entitlement and serves only about one-quarter of eligible households. Researchers know a lot about outcomes for the lucky few who receive assistance, but what about those who lose it? In the largest study of its kind, a team from the Urban Institute, including Robin E. Smith, Susan J. Popkin, Taz George, and Jennifer Comey, examined the post-assistance trajectories of families from five US cities. The results point to the need to smooth often vulnerable families’ transition off of housing aid.

Housing assistance in the United States is unusual: unlike many other forms of public assistance, it is not an entitlement and serves only about one-quarter of eligible households. Researchers know a lot about outcomes for the lucky few who receive assistance, but what about those who lose it? In the largest study of its kind, a team from the Urban Institute, including Robin E. Smith, Susan J. Popkin, Taz George, and Jennifer Comey, examined the post-assistance trajectories of families from five US cities. The results point to the need to smooth often vulnerable families’ transition off of housing aid.

There are currently 4.6 million households in the United States receiving federal housing assistance. That may sound like a large number, but demand far exceeds supply. Unlike entitlement programs such as Social Security or food stamps, housing assistance does not reach the vast majority of those who are eligible. As the Urban Institute has illustrated, while the number of families that need assistance grows, a dwindling percentage actually receive aid.

Ideally, those relative few who receive help would be kept from falling into extreme deprivation and, eventually, move from subsidy to financial stability. But is this the case? Is housing assistance a springboard to economic opportunity?

With the release of the largest study to ever explore the issue, we have evidence that the answer is, by and large, no.

From the mid-1990s through the 2000s, the US Department of Housing and Urban Development tested whether incentives to move to low-poverty neighborhoods would improve the life chances of very low-income public housing residents. The Moving to Opportunity (MTO) demonstration program followed the progress of more than 4,600 households from five cities—Baltimore, Boston, Chicago, Los Angeles, and New York. In the process, it yielded 15 years of data, including information on 1,149 households who were no longer receiving housing assistance at the end of the demonstration. For this study, my co-authors and I augmented MTO data with in-depth interviews with some of the families that left assistance in Boston and Los Angeles.

At the end of the demonstration, the income of those who left assistance was 45 percent higher, an average of $23,915 versus $13,153. But income alone does not accurately reflect the changes in leavers’ circumstances. For one, higher income was not always the result of new or better-paying employment, but appeared to be related to marriage, with a new spouse often bringing new financial resources. Furthermore, the bump in income, whatever the source, often came with a downside. In most instances, the new income did not offset the loss of the housing subsidy enough to significantly reduce a family’s housing cost burden, but it did render families ineligible for other forms of social welfare, like food stamps. Leavers carried a greater debt load and struggled to afford housing: seventy percent spent one-third or more of their monthly income on rent or a mortgage payment. So despite the addition of a new wage earner or another event that boosted cash on hand, after leaving assistance, most families still faced poverty—or near-poverty—and deprivation.

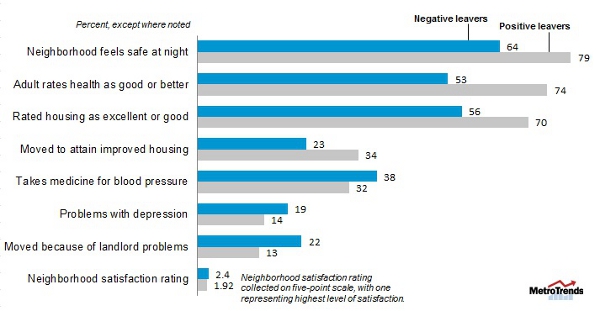

The extent of that deprivation often depended on the reason a family left assistance. Some exited for positive reasons, for example, a bump in income that pushed them above the threshold to qualify for a subsidy, while others left for negative reasons, including eviction or violation of program rules.

This difference mattered.

As a group, positive leavers reported better mental and physical health than those still receiving assistance. They were also five percent more likely than the assisted to indicate that they had moved to a better neighborhood and 21 percent more likely to say they feel safe in their neighborhood at night.

By contrast, negative leavers looked a lot like those still on assistance, minus the income support. Nearly half of negative leavers, 46 percent, reported experiencing homelessness at some point (either before or after receiving aid).

Figure 1 – Housing, Neighborhood, and Health Characteristics of Positive and Negative Leavers (percent, except where noted)

For families in the Moving to Opportunity demonstration, housing assistance was not a springboard but a safety net. Once it was removed, some were able to increase their incomes, move to better neighborhoods, and report greater mental and physical health than those who stayed. Yet even many of the better-situated families hovered around the poverty line, and some of the least fortunate fell into a deeper level of material hardship.

How might some of the worst of these outcomes be avoided or at least mitigated?

For those who are working hard to improve their situation, it would make sense to gradually reduce their subsidy rather than eliminate it all at once. This gradual reduction should be coupled with financial counseling, including debt repair and budgeting. Some housing authorities are experimenting with these graduated kinds of systems, and HUD should invest in a rigorous evaluation to see if they can help prevent some of the instability we found in our research. At the other end of the spectrum, housing authorities should develop intensive eviction prevention protocols, targeting households with lease violations with crisis intervention services to try to ensure they remain housed. And, if they can, housing authorities should find partners who can help them provide wrap-around services to target at-risk families, such as those provided through the Urban Institute’s dual-generation HOST model. HOST provides vulnerable families with intensive case management (low caseloads and frequent contact), clinical services, and employment services for adults coupled with mental wellness and out-of-school time programs for youth. Services like these are costly, but without them, our research shows that troubled families are likely to end up in the homeless system, where the costs to help them will be far higher.

This article is based on the paper, ‘What Happens to Housing Assistance Leavers?’ A version of the article appeared on the Urban Institute’s MetroTrends blog. It is posted here with explicit permission from the Urban Institute and is not part of USAPP content available for reuse under a Creative Commons license.

Featured image credit: trevor.patt (Flickr, CC-BY-NC-SA-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ofESji

_________________________________

Robin E. Smith – The DeBruce Foundation

Robin E. Smith – The DeBruce Foundation

Robin E. Smith is a senior research director at the DeBruce Foundation and a former senior research associate at the Urban Institute. Much of her work focuses on vulnerable populations and how where people live influences their lives. Smith is a seasoned evaluator of federal housing programs, having investigated long-standing federal interventions such as CDBG and public and assisted housing as well as the latest generation of comprehensive community development initiatives like Choice and Promise Neighborhoods.

Susan J. Popkin – The Urban Institute

Susan J. Popkin – The Urban Institute

Susan J. Popkin is both director of the Urban Institute’s Program on Neighborhoods and Youth Development and a senior fellow in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Policy Center. A nationally recognized expert on public and assisted housing, Popkin directs a research program that focuses on the ways neighborhood environments affect outcomes for youth, and in assessing comprehensive community-based interventions. A particular focus is gender differences in neighborhood effects and improving outcomes for marginalized girls.

Taz George – The Urban Institute

Taz George – The Urban Institute

Taz George is a research assistant in the Housing Finance Policy Center. His work focuses on housing and mortgage market trends, in particular housing affordability and access to credit. Outside housing finance, George’s research interests include neighborhood-based inequality and public transit.

_

Jennifer Comey – District of Columbia Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education

Jennifer Comey – District of Columbia Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education

Jennifer Comey is a senior policy advisor at the DC Office of the Deputy Mayor for Education where she works on strategic planning coordinating the traditional and public charter schools. Her current projects include school assignment policies and boundaries, assessing the adequacy of local education funding, and identifying the optimal supply of public schools. Before joining the Deputy Mayor for Education’s Office, Comey was a senior research associate in the Metropolitan Housing and Communities Center at the Urban Institute.