From the Occupy Wall Street movement, to Thomas Piketty’s more recent Capital in the Twenty-first Century, the notion of inequality has become increasingly prescient to politicians and the public in general. In new research, Daniel L. Hicks and Joan Hamory Hicks find that one very visible aspect of that inequality, conspicuous consumption by the rich, is associated with higher levels of violent crime. They write that one potential explanation for their findings is that rising inequality could then increase feelings of relative deprivation among those who are unable to succeed legally, and lead them to commit crimes against their neighbors.

From the Occupy Wall Street movement, to Thomas Piketty’s more recent Capital in the Twenty-first Century, the notion of inequality has become increasingly prescient to politicians and the public in general. In new research, Daniel L. Hicks and Joan Hamory Hicks find that one very visible aspect of that inequality, conspicuous consumption by the rich, is associated with higher levels of violent crime. They write that one potential explanation for their findings is that rising inequality could then increase feelings of relative deprivation among those who are unable to succeed legally, and lead them to commit crimes against their neighbors.

In 2008, using newly passed “right to know” laws, the California newspaper, the Sacramento Bee, created the state’s first publicly searchable database of salary information for all public sector employees. A team of researchers from the University of California, Berkeley and Princeton University ran a clever little experiment in which they emailed a random subset of UC employees to inform them about the existence of this database, and shortly thereafter attempted to survey these employees and others on job satisfaction and job search intentions. The researchers found that when workers who earned relatively less than their peers were informed of the website (and were thus more likely to know their colleagues’ pay), these individuals reported lower job satisfaction and a higher desire to look for new employment.

This research suggests two things. First, most of us are blissfully unaware of our coworkers’ (and likely also our friends’ and neighbors’) exact earnings. Second, learning that one’s economic position is worse than others’ can make people pretty unhappy.

As the world struggles to recover from the Great Recession, interest in confronting economic inequality has been renewed. This has manifested in the growth of populist movements such as Occupy Wall Street, policy proposals like France’s 75 percent tax rate for millionaires, and general discourse as evidenced by Thomas Piketty’s influential Capital in the Twenty-first Century. These developments reflect a notion that growing imbalances could serve to erode key elements of the fabric of society.

One important concern is the potential for such imbalances to foster crime. Growing inequality has previously been shown to be weakly related to rising crime rates, yet this research has focused only on income disparities, overlooking the difficulty involved in observing the income of others. In recent research, we explore the relationship between crime and visible expenditure inequality. In the absence of precise information on others’ income, individuals make educated guesses by observing their expenditure. For example, when we see a friend sporting a fancy new ring, or a flashy car driving down the street, we form impressions of the social and economic status of others, and also of our own place in society. Economists refer to these purchases which confer social status as “conspicuous consumption.”

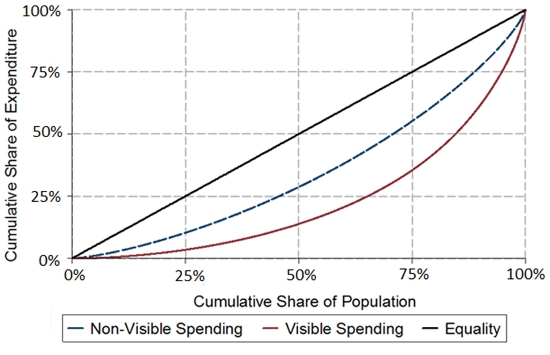

Expenditures on goods and services such as clothing, jewelry, personal care, and vehicles are all highly conspicuous (or “visible”) relative to other expenditures like utilities, food, healthcare, and education. Just how unequal is the U.S. in terms of these different types of expenditure? Figure 1 presents Lorenz curves. These curves plot the fraction of expenditure undertaken by each segment of the population. If the bottom 25 percent of the population (ranked by spending) undertook 25 percent of all spending (and so on for each population group), one would see a 45 degree line like the solid line plotted here—an equal distribution. Instead, in the U.S. the bottom 50 percent account for only around 27 percent of non-visible spending and about 18 percent of all visible expenditure. In other words, consumption, and in particular, visible consumption, is highly concentrated among the very rich.

Figure 1 – Expenditure inequality in the U.S.

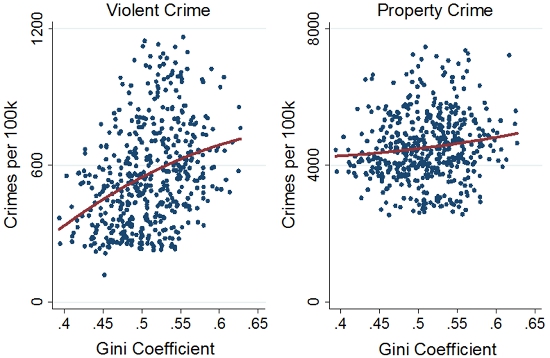

Examining the connection between these types of expenditures and crime within U.S. states over a fifteen year period gives rise to several interesting patterns. First, increases in total expenditure inequality are not robustly associated with increases in crime. However, increases in visible expenditure inequality are associated with elevated levels of violent crime, particularly incidences of murder and assault. This can be seen in the left panel of Figure 2 which depicts the association between state-level inequality in visible expenditure and violent crime rates. Together these two findings suggest that conspicuous consumption provides an important incentive to would be criminals.

Figure 2 – Crime and visible inequality across U.S. states

Note: A higher Gini Coefficient indicates a greater level of inequality

Yet, there is no clear relationship between visible expenditure inequality and property crime (burglary, larceny, and motor vehicle theft), as seen in the right panel of Figure 2. Indeed, once we account for other common determinants of crime and factors like police resources, we find no significant connection between visible expenditure and property crime at all. This is surprising—economic theory suggests that inequality in visible expenditure should lead to higher property crime, because conspicuous spending habits convey important information about the potential benefits of engaging in nefarious endeavors.

Two caveats are also worth mentioning. First, people generally know better than to display lots of expensive, flashy goods in high crime areas. This behavior should make any relationship we measure between crime and inequality appear smaller than it really is, since in high crime areas people would avoid the risk of owning conspicuous goods. A second concern is one of aggregation. Our analysis is conducted at the state level, since the detailed expenditure data we use preserves anonymity by only reporting state of residence of the household respondents. Inequality could vary across geographic areas within states, or the inequality-crime relationship could be more nuanced at the level of individual neighborhoods or cities.

Ultimately, why do we only observe a relationship for conspicuous consumption and violent crime? The answer may be found in prominent crime explanations among sociologists, known as Strain Theory and Social Disorganization Theory. The story goes something like this. Individuals who are unable to attain pecuniary success through legal endeavors over time might develop a sense of disenfranchisement with societal conventions, leading them to view crime as a viable alternative. Rising inequality could then increase feelings of relative deprivation, weaken community ties, and lead individuals to commit crimes—even violent ones—against their neighbors.

This article is based on the paper, ‘Jealous of the Joneses: conspicuous consumption, inequality, and crime’ in the Oxford Economic Papers.

Featured image credit: Chuck Coker (Flickr, CC-BY-ND-2.0)

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/XxcHFA

______________________

Daniel L. Hicks – University of Oklahoma

Daniel L. Hicks – University of Oklahoma

Daniel is an Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Oklahoma. His research centers on economic development with an emphasis on culture, consumption, and gender.

_

Joan Hamory Hicks – Center for Effective Global Action

Joan Hamory Hicks – Center for Effective Global Action

Joan Hamory Hicks is an Assistant Project Scientist at the Center for Effective Global Action, a research center at the University of California, Berkeley. Her research primarily focuses on health, education, and transitions to adulthood among rural African youth.