The null or protective impact of immigration on neighborhood violence is well-documented, but how do cities’ policies towards immigrants influence this protective relationship? Using data from 9,000 neighborhoods, Christopher J. Lyons, María B. Vélez, and Wayne A. Santoro find that neighborhoods benefit more in terms of reduced violence from immigration when they are located in “open” cities that have increased levels of minority representation in elected offices and law enforcement, pro-immigrant legislation, and a large proportion of Democratic voters. Cities that are more closed and have more punitive policies towards immigrants may actually decrease the potential benefits of immigration for neighborhood safety.

The null or protective impact of immigration on neighborhood violence is well-documented, but how do cities’ policies towards immigrants influence this protective relationship? Using data from 9,000 neighborhoods, Christopher J. Lyons, María B. Vélez, and Wayne A. Santoro find that neighborhoods benefit more in terms of reduced violence from immigration when they are located in “open” cities that have increased levels of minority representation in elected offices and law enforcement, pro-immigrant legislation, and a large proportion of Democratic voters. Cities that are more closed and have more punitive policies towards immigrants may actually decrease the potential benefits of immigration for neighborhood safety.

Recent research repeatedly finds that neighborhoods with more immigrants actually have less violence than otherwise expected. Scholars typically suggest that when immigrants move into communities they can strengthen relationships among residents, invigorate local ethnic economies, and help to expand community institutions such as churches, schools, and immigrant-focused agencies. These processes help “revitalize” neighborhoods and fortify the ability of even relatively poor neighborhoods to keep crime at bay. Through our research, we have found that this link between immigrant concentration and reduced neighborhood violence is actually strengthened in cities that are more open to immigrants.

This documented protective association between immigration and neighborhood crime contrasts starkly with public opinion and political rhetoric that equates both legal and illegal immigrants with an array of social problems. Public sentiment fuels the many anti-immigrant policies initiated by cities, such as the mandate among police in Phoenix, Arizona to question all arrestees about citizenship status. Yet, not all cities respond unfavorably to immigrants, and some have even declared “sanctuary” policies that downplay the enforcement of immigration laws. Across the country, cities vary substantially in the social and political environments that promote immigrant concerns and facilitate the ability of immigrants to incorporate into society.

Credit: bbyrnes59 (Creative Commons BY NC SA)

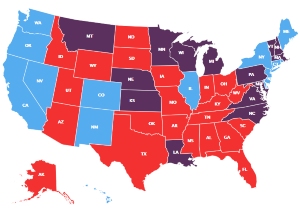

We examined whether the protective relationship between immigration and neighborhood violence depends on a city’s openness to receiving and supporting immigrants. We expect that neighborhoods benefit more from immigration when located in “open” cities characterized by immigrant representation in elected offices and law enforcement, pro-immigrant legislation (e.g., “sanctuary cities”), and a large proportion of Democratic voters. To assess this question, we used unique data on violence and socio-demographic information for almost 9000 neighborhoods within a representative sample of U.S. cities (87 cities with populations of more than 100,000 in the year 2000). This allowed us to measure the ‘openness’ of cities for immigrants, from data on the extent of minority political representation in municipal offices, and law enforcement, indicators of whether public and policy climates favored immigrants, and levels of openness of cities’ governmental structures.

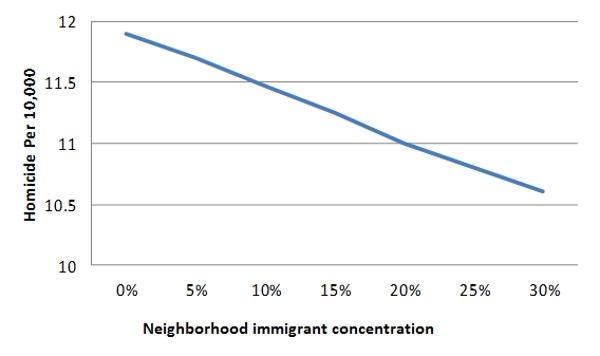

Consistent with the protective hypothesis and contrary to much public discourse, our multilevel analyses reveal that the relationship between immigrant concentration and neighborhood violence (homicide or robbery), on average, is negative across the nearly 9000 neighborhoods we studied. For instance, Figure 1 shows the average relationship between immigrant concentration and neighborhood homicide levels for 87 of the largest cities in the US, holding constant a variety of other covariates at the neighborhood and city levels.

Figure 1 – Relationship between Immigrant Concentration and Neighborhood Homicide

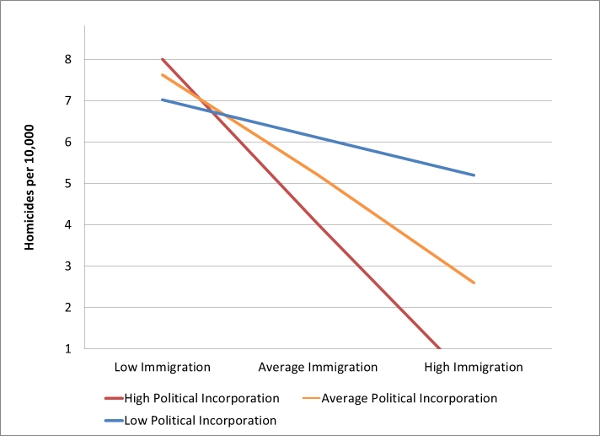

Consistent with our expectations, the magnitude of the protective influence of immigrant concentration on violence varies substantially across cities. For homicides, we found evidence that all but one of our measures of openness to immigrants enhanced the protective influence of immigrant concentration. Specifically, the political incorporation of Asians and Latinos into elected municipal offices, the bureaucratic incorporation of minorities into police departments, the adoption of sanctuary policies, and a relatively large share of Democratic voters all magnify the inverse association between immigrant concentration and homicide. For illustration, Figure 2 shows that neighborhood homicide decreases as immigrant concentration increases and that this relationship is especially notable in cities with greater political incorporation of Asians and Latinos into municipal offices.

Figure 2 – Minority Political Incorporation Influences the Immigration-Homicide Link

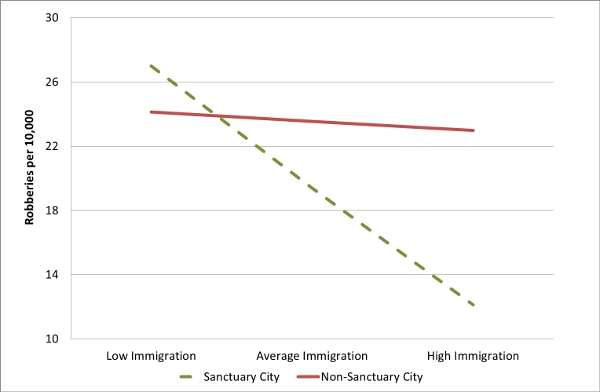

We find similar patterns with robbery—a more common but less reliably reported form of violence. Figure 3 shows, for instance, that neighborhood robbery decreases as immigrant concentration increases. However, this relationship is most precipitous in sanctuary cities characterized by formal policies that limit the enforcement of immigration laws.

Figure 3 – Sanctuary City Policies Influence the Immigration-Robbery Link

Our findings suggest that the protective association between immigrant concentration and neighborhood violence is strengthened in cities that are more open to immigrants. Contrary to public opinion and political rhetoric, our research joins a chorus of others in suggesting that immigrants can make us safer. However, the ability of immigration to translate into less violence partly depends on the social and political climates of immigrant reception. We suggest that closed regimes characterized by limited political support and punitive policies may, ironically, decrease the potential benefits of immigration for our communities. By marginalizing newcomers, less open regimes may set in motion constraints to immigrant incorporation and prosperity that may have less-than-ideal consequences for community viability. We subscribe to the call for evidence-based immigration policies rather than policies and social climates based on fear and sometimes unfounded assumptions of immigrant criminality.

This article is based on the paper “‘Neighborhood Immigration, Violence, and City-Level Immigrant Political Opportunities” in the American Sociological Review.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of USApp– American Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1ghqPua

_________________________________

About the authors

Christopher J. Lyons – University of New Mexico

Christopher J. Lyons – University of New Mexico

Christopher J. Lyons is an Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. His work focuses on race/ethnicity and sociolegal control, and integrates insights from social disorganization, public social control, racial politics, and political economy perspectives to account for the spatial distribution of crime across neighborhoods.

María B. Vélez – University of New Mexico

María B. Vélez – University of New Mexico

María B. Vélez is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. Her work focuses on understanding how racial and economic inequalities pattern urban crime at the individual, neighborhood, and city levels. She also seeks to understand how larger political and economic contexts shape neighborhood dynamics relate to crime.

Wayne Santoro – University of New Mexico

Wayne Santoro – University of New Mexico

Wayne Santoro is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at the University of New Mexico. His work lies at the intersection of race, politics, and social movements. He examines how blacks and Latinos have mobilized to compel governments to become responsive to community concerns as well as how these populations in turn have been affected by government actions. Other work investigates Mexican American political-mobilization and the political dynamics that took place during the decline of the civil rights movement.