“To explore” or the power of small words in social research

It’s interesting how the notion of “exploration” or “to explore”, beyond any formal or agreed definition, has gained a privileged position within qualitative research. Other notions such as “to understand” or “to describe” somehow fail to express the specific ethos of the qualitative endeavor. On the one hand, exploration seems to point to an initial examination of a relatively unknown situation or phenomena, a clarifying stage in a continuum that ends with a proper search for explanation and causality. But the idea seems to have gained a level of autonomy regarding this continuum. Decades of mistrust against realism warns us against a naïve conception of social reality as a series of circumscribed objects out there, and as social research as a form of legitimate access to them. In front of this the idea of “exploration” seems to suggest a reflexive process, one that is open to change, and, somehow, open to the essential openness and ongoing-ness of social reality.

In this sense, more than a clearly defined stage in a methodological process we talk about the “exploratory” character of a project, and this shift from the verve (to explore) to the adjective (exploratory) seems to reveal a specific awareness of the possibilities and limits of social research.

Considering the multifaceted set of images and notions mobilized every time we decide to “explore” instead of “explain” or “understand”, it seems important to reflect on how and why certain concepts have gained a particular persuasive power in expressing what social research is supposed to achieve. Of course, this blog entry won’t do that. Instead, I only want to provide a basic starting point. And when it comes to words, the starting point can be searched in their origin.

According to Douglas Harper’s Onlyne Etimology Dictionary:

Explore (v.)

1580s, “to investigate, examine,” a back-formation from exploration, or else from Middle French explorer (16c.), from Latin explorare “investigate, search out, examine, explore,” said to be originally a hunters’ term meaning “set up a loud cry,” from ex- “out” + plorare “to weep, cry.”

And the origin of the word, according to the online Oxford Dictionary

Mid 16th century (in the sense ‘investigate (why)’): from French explorer, from Latin explorer ‘search out’, from ex- ‘out’ + plorare ‘utter a cry’.

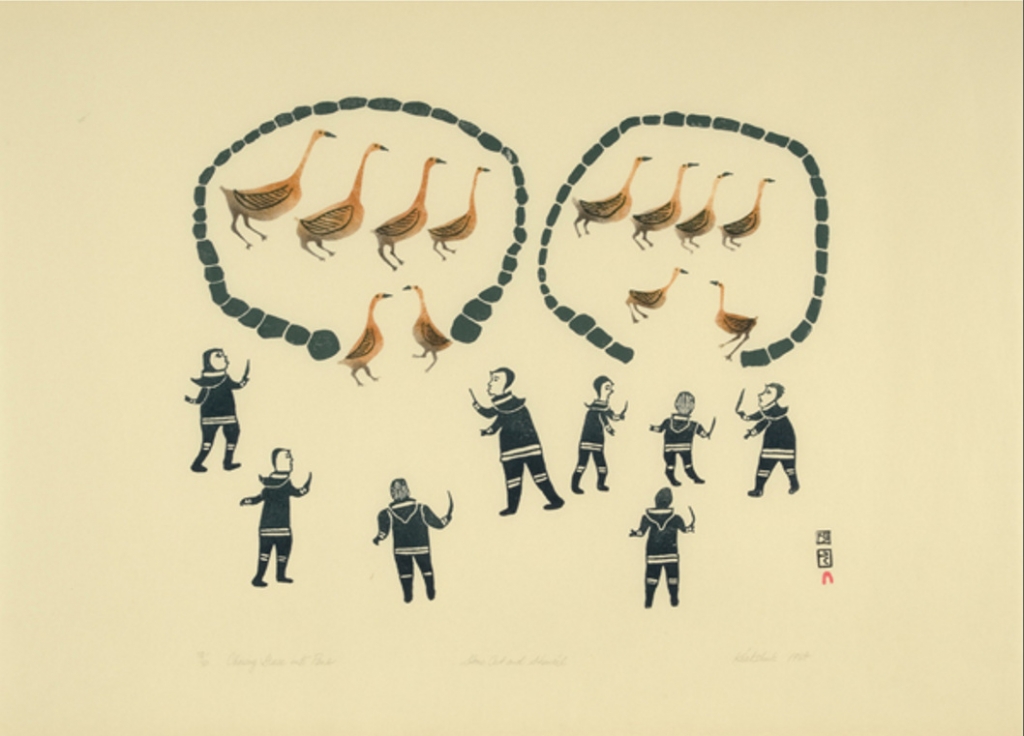

To “set up a loud cry” seems to be the most interesting and unexpected concrete practice associated with the origin of the word. According to some, this relates to a hunting technique that consisted in encircling and animal by shouting loudly, forcing him to move in a certain direction. A collective, highly visible endeavor intended to move something out of darkness towards visibility. Something that one do with reality in order to, then, capture it.

Do we gain something out of this ancient etymology? In my view, looking at the origin can illuminate new and enriched meanings for the words we use. And this is precisely the case with the notion of exploration. The Tufts University Latin Word Study Tool defines the Latin root “exploro” as “to cause to flow forth, bring out, search out, examine, investigate (…)”. This further confirms how the notion of exploration implies positions the exploring subject and the exploring endeavour as visible activities in the world. The concrete origin of the word invites to reconsider and deepen the reflexive orientation that somehow underpins the way we use it, because exploring points to the self-implication in which every project of social research is based, and the strategic use of this self-implication (not its denial) in the process of moving something from darkness into clarity.

Cristian R. Montenegro is a PhD student in the Department of Methodology at LSE.