“The endeavour, either by the state or individuals, to avoid offline activities to contain the virus, has adversely induced a new form of virus, that is digital surveillance, that has infiltrated everyone’s digital devices”, write Dr Sokphea Young (Honorary Research Fellow at the University College London)

_______________________________________________

Introduction

In Southeast Asia, Cambodia is the most impoverished nation whose economy relies on garment and manufacturing industries, apart from tourism and agriculture. The country’s garment and manufacturing sector, especially the garment and footwear industry, emerged in the early 1990s after the first general elections organised by the United Nations Transitional Authority in Cambodia. The United States and the European Union (EU) have supported Cambodia’s export-driven economy through their Generalised Systems of Preferences (GSP) and other trade schemes. The EU, for example, has allowed Cambodia to export duty-free and quota-free to its market since 2001 under the Everything but armed (EBA) scheme. These have boosted Cambodia’s garment sector that now employs about 600,000 Cambodians, most of whom are women from rural areas. With the support of the garment and other industries, Cambodia has managed to significantly reduce poverty and transformed its economy to become a lower-middle-income country in 2016. Annually, Cambodia exported about EUR4 billion (2017-2019) (European Commission 2020) and USD 4 billion (2017-2019) (United States Census Bureau, 2021) of apparel products and goods to the EU and the US markets, respectively. As such, the manufacturing industry contributes about 10 per cent (2017-2019) to the Cambodian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) (World Bank, 2020).

While these supports are significant to the country and her people, the Royal Government of Cambodia’s human rights, and freedom of association and speech, and democracy in general, have been sabotaged as the country has leaned towards authoritarianism, including the dissolution of the prominent opposition party, Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP) in 2017, and the on-going intimidation and spurious arrests of human rights and environmental defenders, restricting space of civil society organisations. These restrictions have provoked the EU to withdraw its EBA scheme to Cambodia, harming workers and its related sector. Many factories were forced to shut down without proper indemnities for the employees.

Coincided with the imposing tariff by the EU, Cambodia’s economy, especially its garment and manufacturing, are doubly punished by the emergence of coronavirus (COVID-19), which spread across the world. Not only have pandemic severely disrupted the global supply chain and markets of garment and manufacturing industries, leaving many jobless, but it has also affected the entire country’s socio-economics. The lack of proper remedial measures to the impacts by the government has sparked dissatisfaction, provoking activism. Amid the country’s leaning toward authoritarianism as manifested by the 2018 election, and the restriction imposed by the government to contain the virus, many were forced to stay at home, compelled to subscribe to digital platforms for study, works, communication, and activism. This has reframed those who have been affected by the EU’s sanction and pandemic not to stage offline (on-street) but online activities to advocate for better solutions.

In this blog, I seek to understand online activities and activism during the pandemic and examine the adverse consequences of offline avoidance in the time of the pandemic. This blog argues that the endeavour, either by the state or individuals, to avoid offline activities to contain the virus, has adversely induced a new form of virus, that is digital surveillance, that has infiltrated everyone’s digital devices. More than the panopticon of the virus, which may be observed as symptoms showed, the new form of digital virus embodies and incubates in every device, smartphone, without showing a symptom like COVID-19. While social media is a COVID-19 free platform for ordinary citizens and activists to connect and express their concerns during the pandemic, this platform is an invisible hand of surveillance of the governed body.

This blog is written based on my on-going observation of Cambodia’s socio-political and technological development, employing digital ethnography to collect data from digital sources and from observing relevant social media pages and profiles. Quantitative data presented in this blog is acquired from using Google Search, focusing on “news” media outlets captured by Google search engine.

The remainder of this blog begins with a discussion about conceptualising how digital media become a new form of digital virus, a form of the pandemic that is neither known to us, in the context of surveillance. It then illustrates how COVID-19 induces Cambodians to subscribe to social media and digital devices before providing evidence on how the latter would strengthen an authoritarian surveillance system.

Panopticon of virus and digital technologies

The digital community has been recognised as a modern tool of human development and evolution. Many have been impressed by this evolution as digital machines and devices can process data and circulate images and voices from a community to another. Kittler (2010, p.11) argues that “machines take tasks – drawing, writing, seeing, hearing, word-processing, memory and even knowing – that once were thought unique to humans and often perform them better”. Given this capability, digital devices and machines like smartphones and cloud devices, become a modern type of panoptic tools incubated in our everyday lifestyle. The devices and the internet are now replacing our basic needs. Drawing on Foucault’s (2012) conception of the panoptic prison cell, these devices gradually observe and incubate in our body and mind without warning us; health applications are exemplars in this context. It is like a virus that has affected us by having not given us a symptom of it. As we unintendedly concede or consent to do so, this new type of digital virus has extracted our personal and privacy data for buyers’ commercial and political purposes. Zuboff (2019) rightly illustrates that access to the digital community exposes oneself to a significant risk. It is a risk of losing or co-opting their privacy rights, rendering privacy data (our private space in essence) to the corporate giants. Having submitted to the machine learning system, holding the state and politicians accountable to citizens, primarily through activism, is facing difficulties. More often than not, for profit-making purposes, the media corporate capitalists tend to co-opt with the surveillance and authoritarian states to gain legitimate power as in the US presidential and UK parliamentary elections.

Drawing on how activists and state interact in China, MacKinnon (2010) introduces a concept of “networked authoritarianism”, which is a political tactic that creates selective social openings for transparency but, in fact, monitors and stifles dissents (He & Warren 2011). This networked authoritarianism in the digital era is framed based on the notion of a networked society whose key social structures and activities are organised and linked electronically (Castells 2010). The networked authoritarian Chinese government, for instance, allows people to use the internet to submit grievances or unjust activities, but the government also monitors who reports or submits the grievances. In China, only specific applications or types of social media platform are allowed to use, and this eases the ruling regime to scrutinise and surveil the users to curb outrageous dissents. The use of these digital communication technologies also induces side effects, one of which is the exposure to the surveillance system (Howard & Hussain 2013), a critical concern for digital activism in the non-democracy ruling systems that appear to have adopted the Chinese authoritarian style of panoptic surveillance.

Cambodia’s online community and activism amid the pandemic

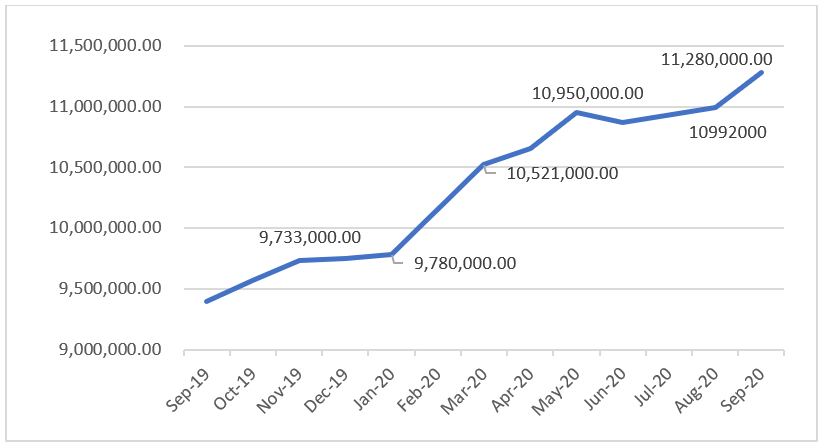

The foregoing theorisation of how digital communication and technologies render risks reverberates Cambodia’s and other countries’ situation during the pandemic. Following the instruction of the government not to mobilise or conduct physical contacts, especially in education and office works, the pandemic has forced millions of Cambodians to subscribe to digital devices and communication platforms. By September 2020, about 67% (11.28 million of about 16 million) of Cambodians have subscribed to Facebook (NapoleonCat, 2020), making this social media site a popular means of communication among Cambodian people, particularly youth. This figure climbed from about 9.73 million subscribers in December 2019, before the pandemic, and it gradually increased to 9.78 million users in January 2020 when the pandemic was not widely spread into the country. As the COVID-19 began to import to the country in early February 2020, the number of subscribers surged rapidly to 10.52 million in March and 10.95 million in May the same year (see Figure 1). Young adults and children are among the new subscribers with the age range between 13-17 (7.8%), 18-24 (31.4%) and 25-34 (47.5%) as of March 2020 (NapoleonCat, 2021). Likewise, the number of cellular smartphone subscribers also increased as these devices are required to access social media: Facebook, Telegram and YouTube. International Telecommunication Union (2020) reports that the number of mobile cellular phone subscribers in Cambodia increased from 19.42 million in 2018 to at least 21.42 million in 2019. Compared to the total population of 16 million, 2019 data suggests that a Cambodian could afford at least two phones (Young 2021a). Given the low quality of education, the higher percentage of young subscribers causes critical concern on data and privacy issue, and the users’ rights. These young adults and children subscribe to the internet and social media for online education, watching Livestream lectures or pre-recorded video teaching. Albeit the supervision of their parents or guardian, we have seen many of these users are addicted to online movies on YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok, online game, and exposed to inappropriate contents, instead of access to teaching materials.

Source: Author’s compilation from NapoleonCat, 2020

Not only did the pandemic compel ordinary Cambodians to go online, but it also affected Cambodia economy (coincided with the partial withdrawal of the EBA programme). Coupled with the decline of the purchase order in the apparel and footwear industries, Cambodia’s GDP growth in 2020 was predicted to be between -1 to -2.9 per cent, and that about 1.76 million jobs were also at risk (World Bank, 2020). The World Bank emphasised that the poverty rate in the country is to increase by 20 per cent. Some factories closed down as they were either affected by the impact of COVID-19 on the global supply chain or by the withdrawal of the EU’s EBA scheme. This raised the affected population’s concerns, especially garment and manufacturing workers, to seek the government’s intervention and remedies. Given the government’s restrictions on physical movement, the ability to lobby the government and concerned stakeholders were limited to online activities. They began to use social media platforms such as Facebook to express the grievances such as indemnities (as the factories were shut-down) and dissatisfaction with the government’s intervention in remedying job loss and cut due to COVID-19. Either made by individuals or media outlets, news on job losses and cuts, people’s dissatisfaction with the government measures was widely observed.

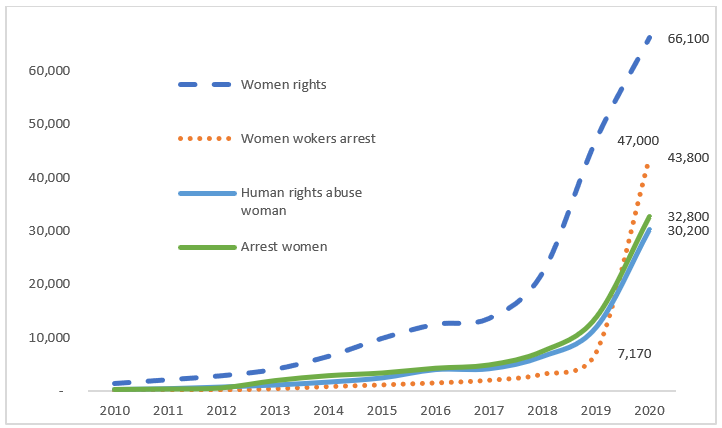

Source: Author, 2021

As I traced the development of news on women workers on Google Search (see Figure 2), we found that “women rights Cambodia” are often reported by local and international media outlets: the number of its citations has increased from 47,000 times in 2019 to 66,100 time in 2020 (September). While digital and social media become platforms for disgruntled women to frame and amplify their concerns to the public, the endeavour has not been the ideal solution. By querying the term “women workers arrest” in Cambodia, I found that the frequency of the term mentioned in digital media exploded from 7,170 times in 2019 to 43,800 times in 2020 (September). This signified that many women workers or activists were arrested, detained or harassed by the authority. For instance, a women worker, who was a member of a union, was arrested because her post on Facebook criticised her employer, who dismissed 88 workers without following the government of Cambodia’s guidelines and instructions not to cut jobs but reduce workers’ wage government instruction (Kelly & Grant 2020). Following her post, the employer decided to re-employ the workers, and she immediately deleted her post from Facebook, but, still, the employer filed a complaint against her accusing that she created fake news to defame the company and the buyers. The ability to notice who is posting thing or creating news from their smartphone onto Facebook has indicated how effective the government’s surveillance system is. In one instance, the prime minister of Cambodia who has been in power for more than three decades claimed that smartphone allows the government to track and trace anyone effectively (Young 2021b; Young 2021c). He claimed that “If I want to take action against you, we will get [you] within seven hours at the most” (Doyle 2016). Anyone dares to speak against the supreme leaders and or the governance system; the consequence thereof is predictable based on the statement.

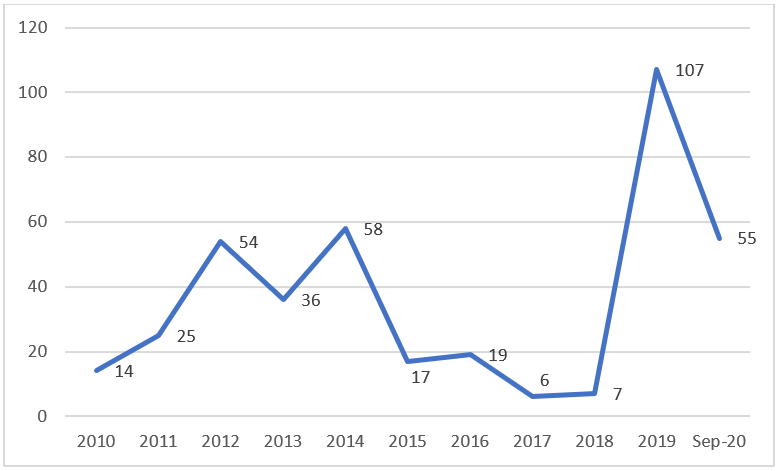

Source: modified from Young & Heng, 2021

While many Cambodians resorted to online to contain and prevent the spread of the virus, human rights, political activists, environmental and human right defenders, workers and protesters also resort to online activities. As they go online, they submit to a new form of authorities or what I call a “surveillance virus”, which surrounds the users every time. As in Figure 3 above, it appears that the pandemic causes a surge of spurious arrests of political activists, environmental and human rights defenders, workers, and protesters. The increase in the arrest in 2019 was induced by two important reasons. First, authorities arrested those activists who were disgruntled with the dissolution of the opposition party (CNRP) in 2017 prior to the 2018 election. The election allowed the ruling party to take control of all national assembly seats and Hun Sen to remain in power for more than three decades (Young 2021c). Secondly, the arrests were made in response to those who supported the attempt of CNRP leader, Sam Rainsy (who has lived in exile abroad since 2016), to return to Cambodia in 2019. As of September 2020, the number of people arrested by authorities increased to 55, alarming the international communities’ concerns over the country’s tendency to practice authoritarianism amid the pandemic. The arrest is enabled by a form of “networked authoritarianism” as put forward by MacKinnon (2010) in China, where the governed body allowed online grievance submissions, but tackling those critical ones as their comments or grievances undermine the ruling regime’s authority and legitimacy. Cambodian activists’ critiques of how the ruling government handled the pandemic and socio-economic issues, and also other social issues during the crisis have been subject to scrutiny and surveillance, of which social media-mediated-devices are invisible tools of the ruling system.

Conclusion

In this blog, I have demonstrated how COVID-19 has affected not only Cambodia’s economy, but also pushed many Cambodians to go online, subscribing to digital platforms. Digital media platforms are believed to help contain the spread of COVID-19, but such endeavour has apparently compelled the users to be infected by a new form of virus, digital surveillance whose symptom may not be diagnosed or known to the users but the governed body. This form of the digital virus has surrounded users, placing the users in a panoptic prison cell of the surveillance system. The users only realise that they are in the cell when the observers/guards (the government in this instance) take actions against them, as illustrated by women workers and activists in the present study and beyond. This new type of virus has tightened the authoritarian surveillance system to effectively monitor the subject’s antagonistic behaviour, citizens and activists, which may undermine the ruling system’s legitimacy.

Footnote

[1] I used key terms to search on Google, and classified the results of the search by year. To ensure that all search results are about Cambodia, “Cambodia” are always added to individual terms when searched on Google, “Women workers arrest Cambodia” for example. These search results are limited to “news” rather than “all” results in the Google search engine.

References

Castells, M 2010 The rise of the network society: Information age: Economy, society, and culture. West Sussex: Willey-Blackwell.

Doyle, K 2016 Cambodian leaders’ love-hate relationship with Facebook, 7 January 2016. Available at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-35250161 (Last accessed on 20 January 2021).

European Commission 2020 Countries and regions, 18 June 2020. Available at www.ec.europa.eu/trade/policy/countries-and-regions/countries/cambodia/index_en.htm (Last accessed on 26 July 2020).

He, B and Warren, M E 2011 Authoritarian deliberation: The deliberative turn in Chinese political development. Perspectives on Politics 9 (2): 269-289.

Howard P N & Hussain M M 2013 Democracy’s fourth wave? Digital media and the Arab Spring. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

International Telecommunication Union 2020 Mobile-cellular subscription 2020, 18 January 2021. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx (Last accessed on 25 February 2021).

Kelly, A and Grant H 2020 Jailed for a Facebook post: garment workers’ rights at risk during Covid-19, 16 June 2020. Available at https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/jun/16/jailed-for-a-facebook-post-garment-workers-rights-at-risk-during-covid-19 (Last accessed on 20 January 2021).

Kittler, F 2010 Optical media. Cambridge: Polity

MacKinnon, R 2010 Networked authoritarianism in China and beyond: Implications for global internet freedom. Stanford, CA: Stanford University.

NapoleonCat 2020 Facebook users in Cambodia: September 2020. Available at www.napoleoncat.com/stats/facebook-users-in-cambodia/2020/09 (Last accessed on 26 July 2020).

NapoleonCat 2021. Facebook users in Cambodia: March 2020. Available at https://napoleoncat.com/stats/facebook-users-in-cambodia/2020/03 (Last accessed on 1 February 2021)

United States Census Bureau 2021 Trade in goods with Cambodia. Available at www.census.gov/foreign-trade/balance/c5550.html (Last accessed on 15 January 2021).

World Bank 2020 Cambodia economic update: Cambodia in the time of COVID-19. Washington DC: World Bank.

Young, S & Heng, K 2021 Digital and social media: How Cambodian women’s rights workers cope with the adverse political and economic environment amid COVID-19. Lund: Raoul Wallenberg Institute.

Young, S 2021a Citizens of photography: visual activism, social media and rhetoric of collective action in Cambodia. South East Asia Research. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1080/0967828X.2021.1885305

Young, S 2021b Internet, Facebook, competing political narratives, and political control in Cambodia. Media Asia. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01296612.2021.1881285

Young, S 2021c Strategies of authoritarian survival and dissensus in Southeast Asia: Weak Men versus Strongmen. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

Zuboff, S 2019 The age of surveillance capitalism: the fight for the future at the new frontier of power. New York: Profile Books.

* The author received financial support for this article’s research from the European Research Council-funded project entitled PHOTODEMOS (Citizens of photography: The camera and the political Imagination), grant number 695283, at the University College London.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.