“Malaysia is currently battling a third wave of COVID-19, which started in late September. The number of daily cases in this wave is record-breaking with around two-thirds of the cases coming from Sabah, one of the least developed states in Malaysia. “, writes Ahmad Ashraf Shaharudin, a researcher at the Khazanah Research Institute in Kuala Lumpur.

_______________________________________________

The impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic are devastating. Globally, confirmed new cases are trending exponentially. More than 1 million lives were stolen by the end of October. Physical distancing measures to curb the disease are hurting the economy. The IMF projected a contraction in the global economy of 4.4% this year, while Malaysia already registered a 17.1% year-on-year decline in GDP in the second quarter. The country also recorded the highest unemployment rate in a decade in May.

Rubbing salt into the wound, the pandemic coincides with messy political upheaval in Malaysia, following the fallout of the Pakatan Harapan government in February this year, after less than two years in power, and the dissolution of the Sabah state assembly, which necessitated a state election in September.

Open government data for public health

A lack of information and communication in times of crisis is a fertile breeding ground for misinformation. Not only are pseudo-scientific claims making the rounds, but a study conducted by the Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia (ISIS) also found that indeed a majority of false COVID-19 related claims spread in Malaysia pertained to authority’s actions and community outbreaks. Misinformation has the potential to undermine the public health response and aggravate public anxiety.

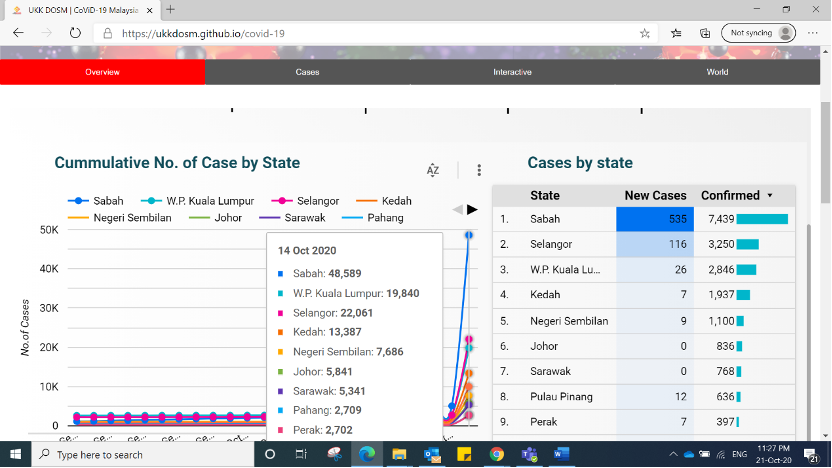

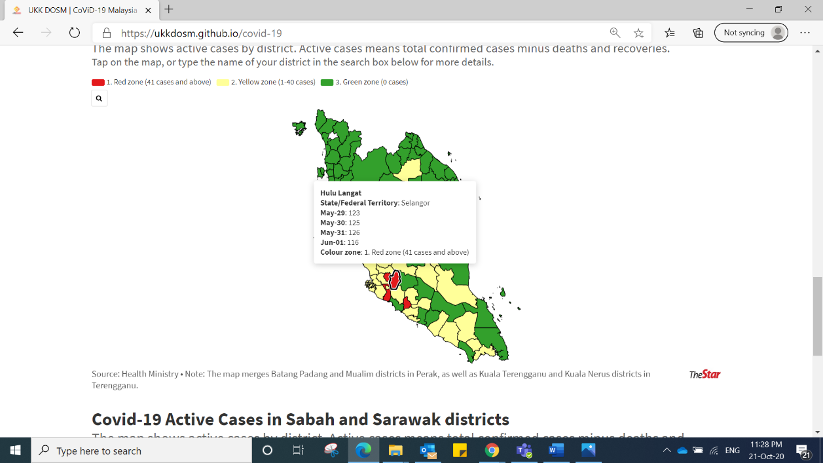

Malaysia definitely has much room for improvement in the dissemination of COVID-19-related information. Although the Ministry of Health (MOH) publishes the daily number of new COVID-19 cases and deaths on its website, the information is published in infographics and daily media statements (Figure 1), making tracking the numbers difficult. On the other hand, while the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) also has a special website that presents COVID-19 data with seemingly better visualisations, the data is outdated. At the time of writing, data at the state level on the website was last updated 7 days ago (Figure 2) while data at district level was updated more than 3 months ago (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Screen capture of MOH COVID-19 website – data is presented in daily infographics and media statement

Figure 2: Screen capture of DOSM COVID-19 website (1) – on October 21, the latest published data of new cases by the state is for October 1

Figure 3: Screen capture of DOSM COVID-19 website (2) – on October 21, the latest published data of new cases by district is for June 1

Unlike Singapore and New Zealand, which publish information on public places recently visited by COVID-19 cases, the Malaysian government is quite reluctant to disclose such information. Although this may be justifiable to prevent unnecessary panic, it creates room for assumptions. A vague cluster name—such as Cluster Sentral that led to people assuming (rightly or not) that the location of the cluster was in KL Sentral (the main transportation hub in Kuala Lumpur)—arguably fuels further misinformation. The Malaysian Communications and Multimedia Commission (MCMC) had to debunk a lot of false information related to outbreak locations through the sebenarnya.my portal.

The claim that Malaysia does not conduct enough testing for COVID-19 is often propagated even in public fora, which the MOH refuted through its Director General’s briefing and a social media post. Putting the validity of the claim aside, it is understandable that this claim is rife when testing data is not accessible except in occasional media statements. This is unlike countries such as Australia, New Zealand and Finland that provide accessible and up-to-date testing data down to the state or municipal level in their COVID-19 data portals.

Malaysia is currently battling a third wave of COVID-19, which started in late September. The number of daily cases in this wave is record-breaking with around two-thirds of the cases coming from Sabah, one of the least developed states in Malaysia. There are concerns that the state’s hospital capacity is reaching its limit. These concerns were proved warranted—the MOH on October 6 stated that the number of beds provided to treat COVID-19 patients is 6,759, but the number of active cases as of October 17 was 6,886. The MOH did, however, clarify on October 17 that the hospital capacity in Sabah has been increased and resources are being mobilised. Nonetheless, one could not help but wonder: had the government published the updated data of available and occupied beds by state and the type of bed (i.e. normal or ICU) in COVID-19 data portal like Austria does, would this concern have cropped up?

Open government data for the economy and societal well-being

The economic and social crisis triggered by COVID-19 is unlike anything we have ever seen. Thus, rapid actions are needed not only on the health front but also on the economic and social fronts. In Malaysia, civil society organisations (CSOs) have been working hard supporting vulnerable communities, small-medium enterprises (SMEs) and front-line workers, especially during the implementation of the Movement Control Order (MCO) that restricted mobility. Meanwhile, local media played a tremendous role in uncovering the plight of impacted communities such as the homeless, petty traders, and migrant workers.

Local think tanks including the Khazanah Research Institute (KRI), the Institute of Strategic and International Studies (ISIS), the Institute for Democracy and Economic Affairs (IDEAS), and the Research for Social Advancement (REFSA) have also been actively publishing special analyses and timely responses on COVID-19 related issues. Areas covered are wide-ranging, from social protection, small-medium enterprises, supply chain, education, to mental health.

The roles played by the CSOs, media, and think tanks were not merely nice-to-have but were necessary. The capacity of the government, especially in facing the greatest catastrophe of our time while grappling with political friction, is limited. Access to comprehensive and granular data from the public sector could support CSOs, media and think tanks in playing their role more effectively. A few examples follow.

First, due to the MCO, some households lost their source of income and/or physical access to food. There were allegations that food basket aid from the government was unfairly distributed in favour of constituencies represented by the current government’s members of parliament. If the allegations were true, action should be taken to deal with the aid delivery process to prevent political hijacking. Also, there is a need for more transparency on which constituencies deserve to get more aid based on the percentage of the population that is more vulnerable to food insecurity. The latter could be discerned through data. A good example is the spatial data published by the United States Department of Agriculture that shows populations with low income and low supermarket accessibility by census tract (a subdivision of a county).

Second, during the MCO, school and higher education students were forced to conduct online learning. This, of course, disproportionately affected children with limited digital access. While researching this issue and trying to estimate the number of children that would be affected, I realised that the latest granular education statistics published are for 2017 and they are in a PDF document. This is a classic example of a data hindrance that researchers often face, which affects the ability to conduct an accurate and timely analysis that is especially needed in this time.

Since massive public spending during this time is expected and even urged, the transparency on the use of public funds is important now more than ever. To date, the Malaysian government has allocated RM295 billion in three COVID-19 special packages[1]. Tracking how this money is spent is important for policy evaluation, which would help in deciding whether a particular programme should be continued or a different strategy is required, as well as to prevent leakages. The Ministry of Finance Malaysia (MOF) published regular reports called LAKSANA that provide information on money spent from the COVID-19 packages. However, improvements need to be made in reporting standardisation and machine readability aspects.

New Zealand’s appreciation of open government data is worth learning from. Its COVID-19 data portal compiles a wide range of granular, high frequency and near real-time economic, health and social data. Besides COVID-19 confirmed cases and testing data, data published in the portal include employment data, mental health data, income support data, personal finances data, and even COVID-19-related scam data. Data is available in a machine-readable format and is downloadable in bulk. The portal also has a chat-box for users to request information with a promised maximum turnaround of two days.

Likewise, Eurostat, the statistics organisation of the European Union (EU), gathers datasets relevant to COVID-19 in one place. Data covered include household accounts, labour indicators, digital access data, overcrowded dwellings data and agricultural production data.

The state of open government data in Malaysia

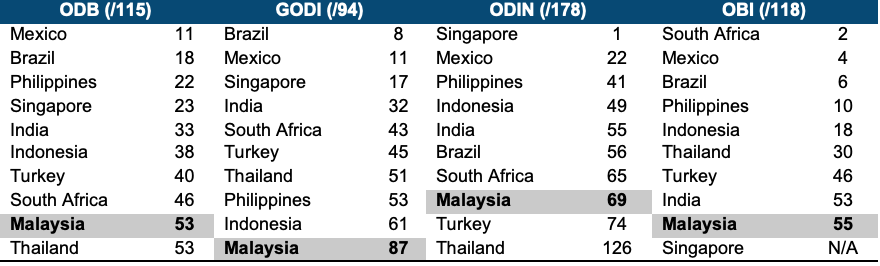

Despite open government data being one of the Malaysian government’s focus areas as stipulated in the Department of Statistics Malaysia (DOSM) Transformation Plan 2015 – 2020, the Public Sector Information and Communication Technology Strategic Plan 2016 – 2020 and the Communications & Multimedia Blueprint 2018 – 2025, Malaysia still has a long way to go in this aspect. Malaysia trails the Philippines, Singapore and Indonesia and many developing countries in multiple global open government data evaluations (see Table 1)[2].

Table 1: Open government data evaluations, selected countries ODB: Open Data Barometer 2016; GODI: Global Open Data Index 2016/17; ODIN: Open Data Inventory 2018/19; OBI: Open Budget Index 2019

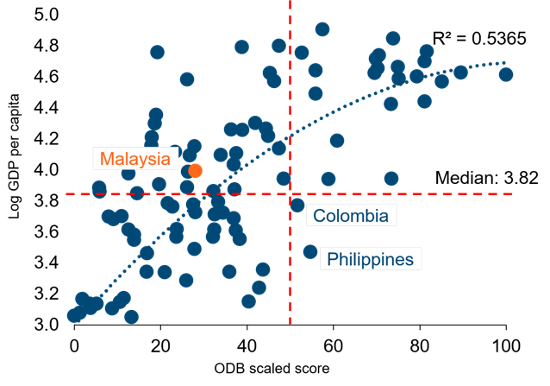

Based on the level of GDP per capita, Malaysia is one of the underperforming countries in open data. Even though Malaysia’s GDP per capita is above the global median, Malaysia’s Open Data Barometer (ODB) score is below half of the full ODB score (Figure 4). This means, loosely speaking, Malaysia has the economic capacity to improve its provision of open government data.

Figure 4: Log-transformed GDP per capita (current prices in USD) versus Open Data Barometer (ODB) score, 2016. (World Bank, n.d.) and Open Data Barometer 2016

The main hurdle for Malaysia is the absence of an overarching policy on open government data. The Malaysian Administrative Modernisation and Management Planning Unit (MAMPU) under the Prime Minister’s Office is the agency responsible for open government data in Malaysia. In 2014, the MAMPU launched the public sector open data portal at data.gov.my, which is supposed to be a one-stop place for all government data. However, other government Ministries and agencies have strong devolved powers in deciding what data is made open (World Bank, 2017). Meanwhile, the DOSM is mandated under the Statistics Act 1965 to collect, interpret, and disseminate economic and social data. The department is seen as the leading data agency in the country since it holds a large volume of data and manages its own portal.

The way forward for open government data in Malaysia

COVID-19 highlights the value of government data and presents an opportunity for Malaysia to accelerate the improvement of open government data. As the first step, Malaysia needs to institutionalise the commitment of making all government data open by default, unless with valid justifications for closure, such as privacy or security concerns. Unlike Indonesia, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam, which guarantee a right of access to information through national law, Malaysia does not have such a legal provision. Of course, this commitment has to come with a strong data management capacity in terms of infrastructure, procedures and skills that guarantee data privacy and security.

Efforts to realise the potential value of open government data should include streamlining the roles of different government agencies in managing data, implementing data standardisation to allow for combinations of different data sets, establishing proper data inventory to encourage usage, improving the user interface of the open data portal, and digitalising old archives. Simultaneously, educating the public on responsible data use and improving their data skills should also be on the agenda.

Footnotes

[1] RM250 billion under PRIHATIN package, RM10 billion under PRIHATIN SME+ package and RM35 billion under PENAJANA package

[2] For the discussion on global open data evaluations, see AHMAD ASHRAF AHMAD SHAHARUDIN 2020. Open Government Data: Principles, Benefits and Evaluations. Discussion Paper. Khazanah Research Institute.

References

AHMAD ASHRAF AHMAD SHAHARUDIN 2020. Open Government Data: Principles, Benefits and Evaluations. Discussion Paper. Khazanah Research Institute.

HARRIS ZAINUL & FARLINA SAID 2020. The COVID-19 Infodemic in Malaysia: Scale, Scope and Policy Responses. Institute of Strategic and International Studies Malaysia.

WORLD BANK 2017. Malaysia Open Data Readiness Assessment. World Bank.

WORLD BANK n.d. World Development Indicators.

* The views expressed in the blog are those of the authors alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.