The 2010s were characterised by the eruption of apparently spontaneous protest across the globe, tackling issues such as democracy, environment, corruption and other social divides. In this post Thomas O’Brien and Remus Creţan consider 2015 anti-government protests in Romania following a deadly nightclub fire in the capital Bucharest and how these combined spontaneity with the urban form to maximise the impact.

The fire that engulfed the Colectiv nightclub in Bucharest on 30 October 2015 eventually resulted in 64 deaths with around 200 people injured. The dramatic nature of the tragedy resulted in considerable shock and an outpouring of grief across the country. Responding to the event, people mobilised in the capital and across the country for nine days, forcing the resignation of the Prime Minister and his government. The impact of the events of that night continue to be marked on the anniversary with the ‘March of Guitars’ involving hundreds gathering at the site of the fire in commemoration. An important question underpinning the protests was what led to such a rapid mobilisation? In our paper, we examine the specific sequence of events that followed the fire and the views of those who participated in the protest. This post summarises some of the key elements, considering the opportunities presented by the urban environment in incubating social movements.

A central feature of the protests that followed the Colectiv fire was their apparently spontaneous character, erupting and growing without warning. Participants reacted with a sense of shock and anger to the loss of life and the apparent failure of the state to guarantee the safety of its citizens. The suddenness and scale of the protests, peaking at about 30,000 people in Bucharest on 4 November, was an important feature of their apparent impact. Addressing the issue of spontaneity in protests, Snow and Moss (2014: 1123) argue that their importance rests not in the fact ‘that spontaneous actions or events are random or unpredictable, but rather that they are not premeditated or part of a formalised system of action’. This is reflected in the Colectiv protests, as they presented an opportunity to break free from and challenge the existing structures, in particular the sense of entrenched impunity and corruption of the state.

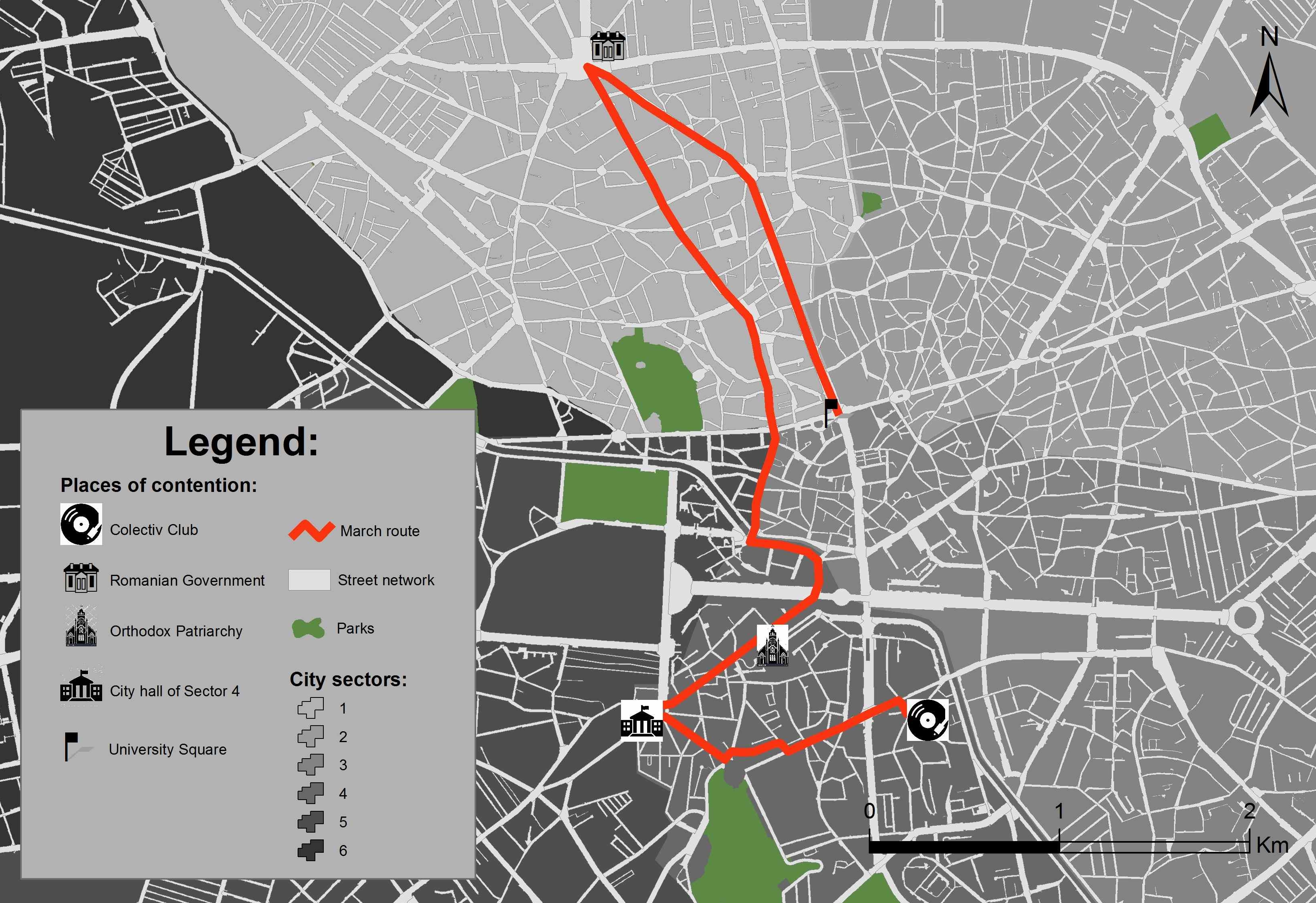

The protests were also rooted in the urban space and a shared understanding of what it represented (see Map below). Targeting key sites, such as government buildings enabled protesters to identify and target those deemed responsible for the catastrophe. At the same time, they also drew on memories of past events, marching to and from University Square (Piaţa Universităţii), a key site during the 1989 revolution that led to the fall of Nicolae Ceauşescu. While cities incubate social movements, monumental character of Bucharest, with its ‘opened up… widened, straightened streets’ (O’Neill, 2009: 104) facilitated the movement of large-scale protests. Viewed in this way the protests can be seen as telling a story through movement, identifying perpetrators and recognising past heroes, while also creating future possibilities.

Key to the scale of the protests was the role of emotion. While the catastrophe at the Colectiv was linked to longstanding injustices around issues of corruption, its form made it more powerful. In our research we found that protest participants referred to a complex mix of emotions, representing the complex nature of the events. Anger, fear, and sadness featured prominently, as they mourned the people who had lost their lives. These emotions also related to the wider failings and the sense of an opportunity missed following 1989. Positive emotions such as happiness and pride were also present, as people recognised the latent potential within society to challenge deep-rooted, structural inequalities and problems. These also enabled participants to call on feelings and experiences linked to 1989, suggesting that things could be different.

The short-term effects of the protests were dramatic, as the government and other local officials were forced to resign from office. In the longer-term, the impact has been more limited. Corruption continues to dog the country and the same political actors are in positions of power. The degree of continuity is reflected in the fact that the investigation into who was responsible was still taking place on the fourth anniversary, with few prosecutions having taken place. This raises questions about the lasting effect of such mobilisations and whether they can actually shift the underlying structures that lead to inequality and injustice.

A more positive reading of the protests following the Colectiv fire, as well as the Autumn protests of 2012 and the anti-corruption protests of 2017, is possible. Looking beyond the formal political arena, the mobilisations can be seen as a sign of hope, pointing to the possibility of alternative visions. Following Vasudevan (2015: 318), protest can demand ‘a recognition that the city encompasses a wide range of political imaginations and that a conceptual architecture is needed that accommodates this diversity’. Seen in this light, the protests represent an ability to advance an alternative, challenging trends of disengagement and depoliticisation. Whether this will lead to any substantive change remains to be seen, but it does reflect a desire to move beyond the past and contribute to the idea of Romania as a European state.

The protests that followed the Colectiv fire were iconic, as they convulsed the nation and led to dramatic political change. At the same time, they were also reflective of a broader pattern of behaviour in Romania and across the European continent. Frustration with the status quo has seen the fall of governments in states from Iceland to Bulgaria. Paying closer attention to the nature of these protests is important in developing our understanding of the factors that are animating and reshaping established social and political certainties.

This post draws on: Creţan R. and O’Brien, T. (2019) ’Corruption and Conflagration: (In)justice and Protest in Bucharest after the Colectiv Fire’, Urban Geography. Doi: 10.1080/02723638.2019.1664252.

Thomas O’Brien is a Lecturer in Political Sociology in the Department of Sociology, University of York. His research addresses issues of environmental sociology, democratisation, leadership and social movements. Recent work in Australian Geographer, British Journal of Sociology, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Journal of Contemporary European Studies.

@TomOB_NZ t.obrien@york.ac.uk

Remus Creţan is Professor of Human Geography at the Department of Geography, West University of Timişoara, Romania. His research has considered regional and local identity politics as well as issues connected to urban marginalization of the Roma population, political ecology and the spatial expression of protests in Romania. Recent work in International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, Urban Geography, Environmental Politics, Area, Eurasian Geography and Economics, and Identities – Global Studies in Culture and Power.

@RemusTim remus.cretan@e-uvt.ro

References:

O’Neill, B. (2009) ‘The Political Agency of Cityscapes: Spatializing Governance in Ceausescu’s Bucharest’, Journal of Social Archaeology, 9(1): 92-109.

Snow, D. and Moss, D. (2014) ‘Protest on the Fly: Toward a Theory of Spontaneity in the Dynamics of Protest and Social Movements’, American Sociological Review, 79(6): 1122-43.

Vasudevan, A. (2015) ‘The Autonomous City: Towards a Critical Geography of Occupation’, Progress in Human Geography, 39(3): 316-37.