Moral Foundations Theory suggests that a handful of core values are instrumental in shaping our moral views, and that this can account for the increasingly polarisation we are seeing in Western democracies. Tamim Mobayed has recently tested the theory in among religious groups in Britain, and concludes that it is a useful tool through which we can understand religious and secular worldviews.

When certain psychological tendencies such as personality traits and mental health are examined, an individual’s level of religiosity has been found to be a relevant factor in their resultant classification. More recently, Moral Foundations Theory (MFT) suggests that religious difference is also present with regard to moral values. Given the moral rooting of religions, this finding might not come as a surprise.

Moral Foundations Theory

Western moral psychology was founded by Lawrence Kohlberg in 1969. Being a moral monist, he believed that justice was the sole mental process that dictated moral behaviour. From justice, he believed all other moral cognitions stemmed. One significant critique of Kohlberg’s work came from Carol Gilligan, who argued that the moral pathway typically followed by girls could not be accounted for by Kohlberg’s monist position, and argued for the need for a separate care pathway. This gave rise to the moral dualist approach; justice and care.

MFT was developed by scholars Jonathan Haidt, Jesse Graham, Sena Koleva, Matt Motyl and Ravi Iyer. The architects of MFT were striving to identify the core moral domain spectrum of human beings. Attempting to integrate between evolutionary and cultural explanations of human moral behaviour, MFT draws from both branches, as well as from models of the brain. These advocate that the brain is seen to be full of “small information-processing mechanisms, which make it easy to solve – or to learn to solve – certain kinds of problems, but not other kinds”. Explaining this model further, and offering a reconciliation between both nature and nurture, the founders of the theory explain,

“MFT proposes that the human mind is organized in advance of experience so that it is prepared to learn values, norms, and behaviors related to a diverse set of recurrent adaptive social problems”.

The 5 Moral Foundations

- The Care/Harm Foundation

- The Fairness/Cheating Foundation

- The Loyalty/Betrayal Foundation

- The Authority/Subversion Foundation

- The Sanctity/Degradation Foundation

Examining moralities in a range of cultures to mine from them universal moral values, the researchers derived a set of five (or six – some have proposed adding Liberty as a moral foundation) core moral values. The significance afforded to culture in overriding or fuelling moral predispositions allows for a great deal of room for influence on the religious environment of the individual.

The human mind’s ingrained processes are then nurtured, adapted or overridden by the role of culture. Drawing from an analogy of buildings and their foundations, the authors liken nature to the foundations of our mind, with culture influencing how the buildings themselves are built:

“the moral foundations are not the finished moralities, although they constrain the kinds of moral orders that can be built. Some societies build their moral order primarily on top of one or two foundations. Others use all five.”

MFT and Political Differences

MFT has been extensively studied in terms of the different profiles found between political liberals, conservatives, libertarians and so on. Given the broad nature of both politics and religion, the two are often interwoven. Haidt et al. (2009) analysed levels of each facet of the MFT among different religious groupings within the USA.

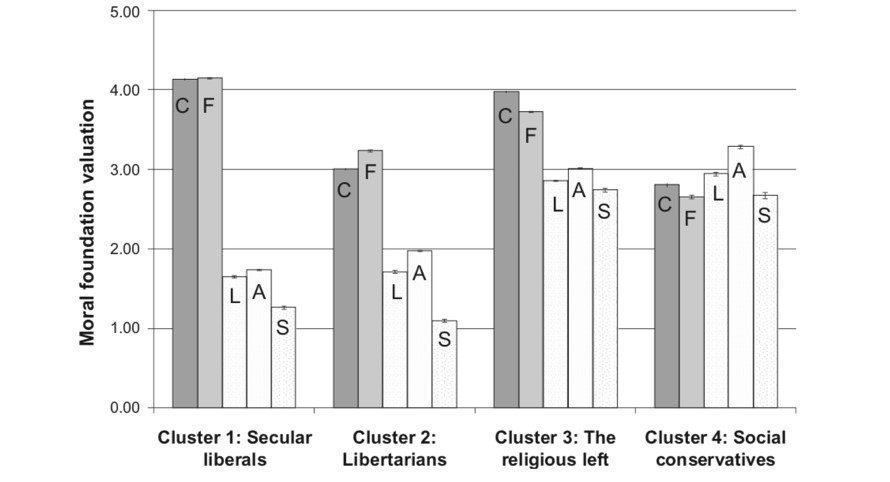

Care and Fairness are typically the only two values that are pronounced for secular liberals, with Authority, Sanctity and Loyalty being deemed unimportant. Social conservatives differed somewhat, with Authority ranking first and the other four close behind. Libertarians echoed the sentiments of secular liberals, the only difference being the lessened intensity of support for both Care and Fairness. The founders of the theory admit that the MFT model struggles to adequately accommodate libertarians, and the priority they place on individual Liberty. The religious left also had Caring and Fairness ahead; however, Loyalty, Authority and Sanctity weren’t too far behind. The differences between religions is currently understudied.

MFT and Religious Differences

In my sample of 1,070 British individuals, differences across religions were found. Just under 62.5% of this sample described themselves as atheist, higher than the 52% reported in one 2018 survey.

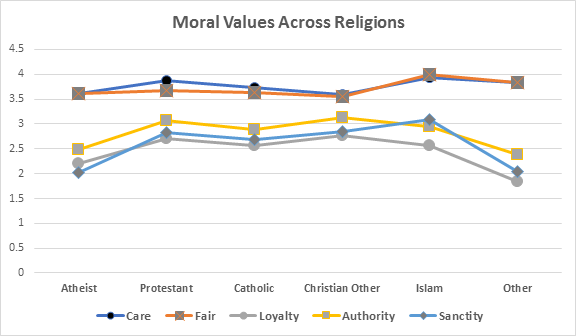

Displayed above, among this British sample, Muslims scored highest in the values of Fairness and Care. As is typically found across most groups, all subsections scored highly in both values. Atheists and other religions (around 20% of whom described themselves as Pagan or Wicca) scored lowest on Sanctity. Certainly, one would expect atheists to score low on sanctity. Would it be fair to say the same of Pagans or Wiccans?

Intra-Christian differences were evident, with Protestants scoring higher than Catholics on Loyalty; Catholic and Muslim scores on Loyalty were similar. This might be explained by conflicted feelings among British Muslims towards allegiances to Britain; ideas such as the Ummah, a transnational Islamic religious bond, might diminish feelings of nationalism among Muslims. However, a BBC poll found that 95% of Muslims feel loyal to the UK. In terms of the high Muslim score for Sanctity, this might explain collective Muslim reactions towards perceived offenses to Islamic sanctity, such as Salman Rushdie’s Satanic Verses, or more recently, the Danish Cartoon controversy.

In terms of Catholic-Protestant differences, this might be a long-enduring hangover from the days of Catholic persecution in England, or again, it might be indicative of a Catholic identity which includes a sense of belonging to an international community, or a Vatican-rooted one. In terms of persecution, reports still highlight issues relating to Catholic treatment in the UK. While considering these differences, it’s important to keep in mind that both Muslims and Catholics scored higher on Loyalty than Atheists and the “Other” grouping.

All religious groups scored higher on Authority than Atheists and the “other religions” group. Both groups also scored lower than the others on Authority. This is typical of a liberal secularist profile.

Conclusion

MFT holds promise in being a framework with which to further understand the ways in which different religions result in different moral values being embodied by the faithful. Of course, factors other than religion will be significant in shaping moral foundations; socialisation, social context and individual differences in personality play a role too.

A body of work is developing that utilises MFT to influence attitudes and behaviours. One study successfully drew from MFT to overcome the “progressive paradox”, a term used to describe a voter intention-behaviour discrepancy, wherein seemingly popular policy positions are not supported at the ballot box. In this study, liberal positions were framed in conservative terms, leading to an increase in support for the liberal policy among conservatives.

A potential avenue of enquiry lies in longitudinal studies that examine the differences that emerge as individuals strengthen in their religious belief and practice, change their religion, or leave religion altogether. Certainly, there is a need for an MFT that is more sensitive to religious nuances, as well as changes in what religion and religiousness means.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.