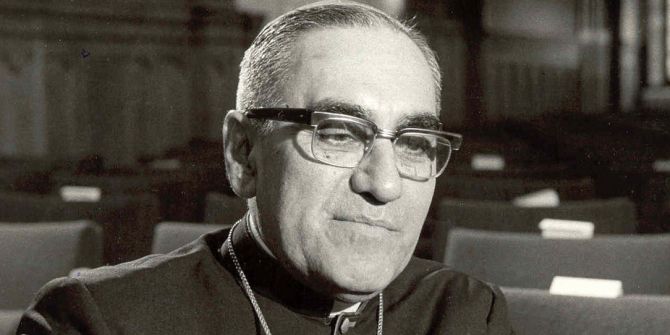

Óscar Romero, the assassinated archbishop of San Salvador, was canonised by Pope Francis on Saturday in recognition of his martyrdom and faithful service to the people of El Salvador. St Romero was a fearless critic of the military government and an advocate for his country’s poor, and Claire Moll sees his determination to address the root causes of poverty as an enduring example for a country struggling to reduce gang-related violence.

Amid the sea of thousands of Salvadorans on Saturday (13 October) stood a man completely still and clearly calculating his every reaction to the Catholic mass he was witnessing. His face on the large screens strategically placed all over the Plaza Civica in San Salvador, Hugo Martinez, the left-wing FMLN’s Presidential candidate, took advantage of the celebrations of the canonization of Saint Óscar Romero to make a clear political statement.

It was not the political figure’s presence alone that made the religious observation of the martyred Salvadoran archbishop political. Killed for “hatred of the faith,” as was officially declared in Rome 38 years later, St Romero became a political figure himself in 1977 after the military government assassinated his friend and fellow priest, Rutilio Grande, for inciting unrest among the landless poor. This “unrest” was Catholic Liberation Theology, a particularly Latin American reading of the Bible focusing on the preferential option for the poor. This historically controversial doctrine suggests that because of God’s care for the poor and Jesus’s political action against the reigning powers of his time, Christians are also called to radical action to break down structural oppression and build God’s Kingdom here on Earth.

St Romero became a very powerful advocate for this world-view. In his homilies, he denounced the government for the various ways it oppressed the poorest of Salvadoran society. He appealed to them to end the killings and to begin reforming land ownership and allow for political representation of the poor. However, his life was cut short before he could see any of these demands met. On 24 March 1980, St Romero was assassinated while giving mass in a hospital chapel in San Salvador. Many cite this date as the beginning of the 12-year-long armed conflict in El Salvador.

Twenty-six years after the war, this canonization comes at a time where, although land reform has happened (to some extent) and the left has its own political party (and 10 years in the presidency), poor Salvadorans are once again experiencing some of the highest levels of violence in the world outside of war-torn countries. Gangs control many areas of the country, but instead of following St Romero’s four decades-old analysis of addressing the root causes of violence and poverty in order to end them, the government has doubled down on its Super Iron Fist policy for combating the gangs. Having followed the advice of Rudy Giuliani’s security consulting firm, prisons are bursting at 300-900% capacity while 10 people are murdered each day. Unfortunately, the end to this failing approach is nowhere in sight. The only sort of aid package for Central America that has been able to pass through the United States Congress in the last decade is one that includes requirements and provisions for this sort of militarized approach.

Although he promised in September to continue to forcefully combat the country’s gang problem, Hugo Martinez’s presence in the celebration of St Romero might signal some sort of hope for a different future. Although rather stoic every time the camera turned to him, one can hope that St Romero’s powerful message for those in power to create grassroots solutions to systemic issues did not fall on deaf ears.

About the author

Claire Moll graduated from the LSE in 2016 with an MSc in Religion in the Contemporary World. She is currently a second-year PhD candidate in Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge conducting field research in El Salvador on rural Evangelical women’s participation in grass-roots development projects.

Claire Moll graduated from the LSE in 2016 with an MSc in Religion in the Contemporary World. She is currently a second-year PhD candidate in Social Anthropology at the University of Cambridge conducting field research in El Salvador on rural Evangelical women’s participation in grass-roots development projects.

Note: This piece gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Religion and Global Society blog, nor of the London School of Economics.

Thanks Claire Moll for your nice piece on the life of our hero in faith st. Oscar Romero, the Martyr.

Would love to read more piece from you especially about Romero’s view on liberation theology looking the situation of his time.