In this blog post (part of the BSc Psychological and Behavioural Science PB101 series), Muhammad Zainuddin (Zain) takes us on a journey with fictional characters Atika and Amy to show how our brains change, with the help of culture.

Did your parents ever warn you that taking drugs will ‘mess with your brain’? You might think this is just some parental myth. In this case, however, you’d be wrong. Taking psychoactive drugs can in fact change your brain structure.

Despite what you may think, brains are not fixed. They are changeable, they are plastic. This concept is known as neuroplasticity (or brain plasticity): our brain is able to adapt and remap its functions (functional neuroplasticity), and even change its own biological structure (structural neuroplasticity).

If you think that your brain is off the hook because you don’t take psychoactive drugs, you’d be wrong. It’s not just drugs that can cause neuroplasticity, it is something that affects us all from our experiences and, by extension, our culture.

Cultures present a constant influx of experiences, norms and behaviours. Our cultural environment provides multiple stimuli that cause our brains to adapt and grow differently across different cultures (as Atika and Amy’s story will show you).

In essence, our brains can change, and culture can change them.

How can culture change our brain?

The culture of a country is often loosely labelled as ‘individualistic’ or ‘collectivistic’. Collectivist cultures like those in Asia, emphasize interdependence or togetherness, whereas individualistic cultures like those in Europe and the US, emphasize independence. Societies and cultures like these share an accumulated wealth of information throughout their population, with different cultures resultantly possessing different ‘cultural brains’. Therefore, it would follow that culture interacts similarly with neuroplasticity; with culture-specific changes present in the brain.

So, although lots of research exists regarding individual factors in relation to brain plasticity, a need arises to investigate brain plasticity across cultures, which incorporate a multitude of these factors.

Atika and Amy

To effectively showcase the cross-cultural differences and the relevance of neuroplasticity in our day-to-day experiences, let’s introduce our protagonists: ‘Atika’ and ‘Amy’. They are two (fictional) women with different cultural backgrounds (collectivistic and individualistic cultures respectively) who will help illustrate cultural differences in the brain through a consideration of several individual factors, starting with memory.

Memory, brain plasticity and a London ‘cabbie’

Atika is a Pakistani student coming to live in London for University. She takes London’s trademark black cab on the way to her accommodation from the airport and is very impressed by how well her cab driver knows the streets of London.

Atika wouldn’t know it, but her cab driver’s substantial knowledge may well be derived not by coincidence, but rather, because of brain plasticity. Maguire and colleagues showed that London cab drivers have a slightly different brain to someone like Atika (or anyone else who isn’t a London cabbie for that matter).

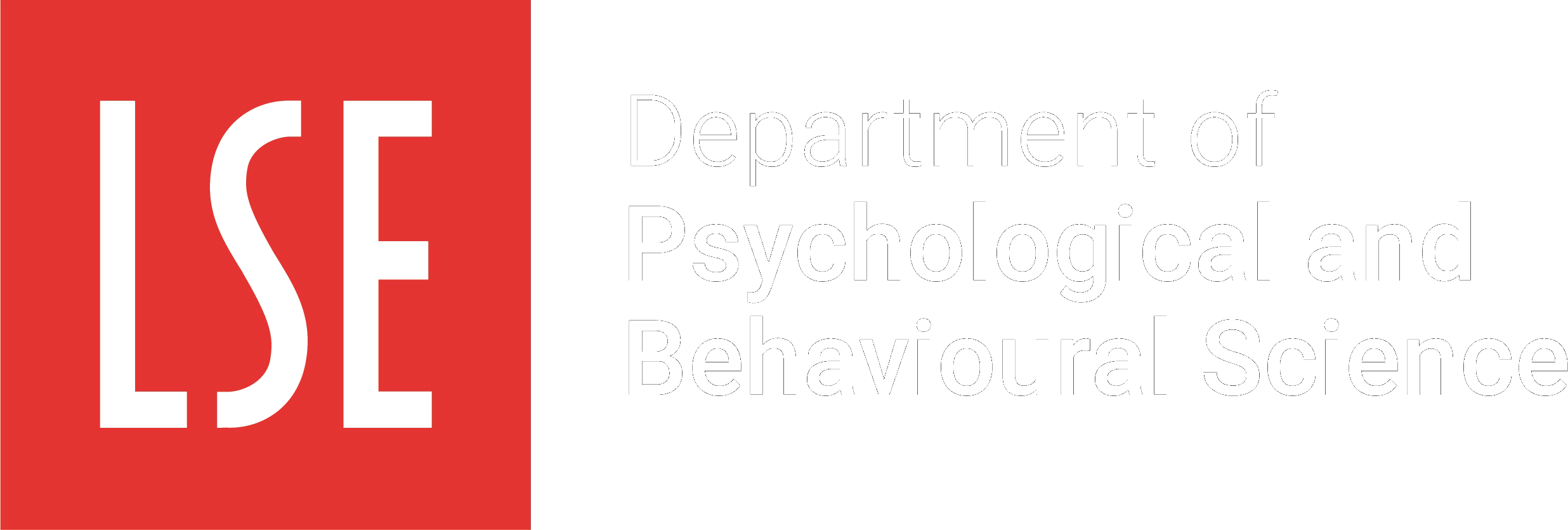

They conducted a study which compared brain scans (MRIs) of London taxi drivers with a control group of those who did not drive taxis. The hippocampus (an area of the brain associated with (spatial) memory) of London cab drivers was found to be significantly larger than that of the control group (see image 1 above).

Repeated exposure to spatial navigation and London’s mapping resulted in a tangible change in the hippocampus of London cabbies in particular; structural neuroplasticity occurred. Reverse causality concerns that undermine this conclusion (individuals with already large hippocampi are predisposed to become cabbies by being able to pass ‘The Knowledge’ test) were settled through finding a positive correlation between hippocampi volume and time spent as a taxi driver.

The impact of literacy on communication

Atika becomes friends with Amy, a British student at the same university. Wanting to introduce Amy to her culture, she locates a Pakistani restaurant to bring her to. It’s a relatively long train ride and the pair are bored, so Amy hands Atika the free newspaper placed behind each seat. Atika is taken aback by how widely read these are, considering the newspapers in Pakistan are hardly read given the country’s low literacy rates.

A recent study found that in literate populations only, brain functions used for facial recognition are centralised to particular areas in the brain (lateralisation). Initially, more areas of the brain are dedicated to facial recognition, but for those that learn to read, some of these areas are adapted and repurposed to pick up on letters and other symbols!

This might teach Atika that largely illiterate, collectivist cultures may not necessarily have a lesser understanding of communication but a different one, focussed more on body language. More areas of the illiterate brain are dedicated to picking up on facial cues where they have not been repurposed for reading.

Vision and Perception

Together, they do the ‘spot the difference’ game on the back page of the newspaper. Amy finds the differences of the cat in the centre, whilst Atika finds the disparities in the background of the image.

Richard Nisbett researched how the perception of a scene varies significantly for individualistic and collectivistic cultures. Those in collectivist cultures were found to look at the picture as a whole (Atika’s focus on the background), whereas individualistic cultures tended to focus on the central or focal point of the image (Amy’s focus on the cat).

This highlights culturally distinct, functional brain plasticity, in the field of perception.

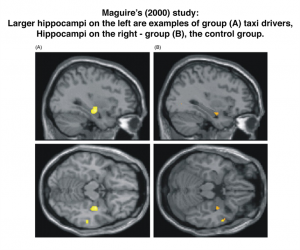

This finding is backed up by cross-cultural studies of the Muller-Lyer illusion, showing that hunters in the Kalahari Desert do not fall prey to the illusion like the Western world does (see image 2 above).

Pain

They finally arrive at the restaurant and not long after, begin eating a spicy meal. Atika, whilst enjoying the taste of home, notices Amy desperately signalling the waiter for more water.

Atika’s appreciation and Amy’s distaste for the spicy meal shows another example of functional brain plasticity: the cultural affinity for the taste of chilli, or more specifically, the capsaicin found in chillies. Without the premise of cultural neuroplasticity, capsaicin should, objectively, be hated universally by all mammals. However, some cultures are able to subvert this through exposure and repurposing of nociceptors (pain receptor) thresholds in the brain, while other cultures simply cannot.

Amy and Atika have shown, in a small way, why we need to consider brain plasticity when we think of ‘cultural brains’, rather than focussing solely on individual factors. Just as Amy and Atika’s cultural backgrounds are different, their brains seem to be too. Culture can permeate something as (supposedly) fixed as our brain structure: our brains can change, and culture can change them.

Images:

- Image 1 by Katherine (Katya) Woollett, Eleanor A Maguire (with edit by Muhammad Zainuddin) is licensed by CC by 3.0 https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Anterior-hippocampal-grey-matter-volume-differences-between-taxi-drivers-and-control_fig3_23950299

- Image 2 edited by Muhammad Zainuddin from https://www.giannisarcone.com/Muller_lyer_illusion.html

- Image 3 by Sanket Shah on Unsplash