Prime Ministers past and present argue the UK wants to recruit migrants who are ‘the brightest and best’. It is usually assumed that more restrictive migration regimes will ensure not only those with higher levels of educational qualifications, but also those who are more motivated, driven and likely to succeed. In one of the first papers to address whether this is actually the case, Renee Luthra and Lucinda Platt find that it is not. Contrary to received wisdom, they show that migrants being relatively high-qualified compared to others in their country of origin does not come with additional economically beneficial skills, characteristics or networks. Moreover, this is particularly the case for those who face a more restrictive migration regime.

Prime Ministers past and present argue the UK wants to recruit migrants who are ‘the brightest and best’. It is usually assumed that more restrictive migration regimes will ensure not only those with higher levels of educational qualifications, but also those who are more motivated, driven and likely to succeed. In one of the first papers to address whether this is actually the case, Renee Luthra and Lucinda Platt find that it is not. Contrary to received wisdom, they show that migrants being relatively high-qualified compared to others in their country of origin does not come with additional economically beneficial skills, characteristics or networks. Moreover, this is particularly the case for those who face a more restrictive migration regime.

It is often pointed out that migrants are selected. That is, those who choose to migrate tend to differ from those who do not in all sorts of ways. One of those ways is that they tend to be more educated than the average for their country of origin. This gives them educational qualifications and related skills which may be valued in destination country labour markets. But even in cases where their qualifications are not recognised, their position in the distribution of qualifications is also considered to be important. Coming from the top of the educational distribution in the sending country – achieving credentials that are more uncommon or difficult to obtain – is expected to indicate a higher social status, or superior levels of ability or motivation, than might be normally inferred from the qualification itself.

As a result, such educational selection has been argued – and demonstrated – to explain the paradoxically high social mobility of the children of some immigrants. It is inferred from such analysis that those who are more selected have the cultural capital, social networks and orientations towards success that are associated with their rank position in the origin country. It could also be they have particular drive and motivation, which they communicate to their children. But despite the widely held view that these relationships between educational selection and positive characteristics exist, and that migrants are particularly high motivated and able, there is remarkably little direct evidence to show this; and that which does exist is equivocal.

In new analysis we address this question head on. We use a rich UK data set, Understanding Society, which has measures not only of education, but also of social networks, cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and health – characteristics that are rarely all observed in studies of immigrant outcomes – for around two-and-a-half thousand immigrants. We then use information on educational attainment of men and women of different ages from 107 different countries, to calculate each immigrant’s rank in the educational distribution of their origin country. This means we can estimate the effect of both educational qualifications and educational selection on labour market outcomes. But more than that, we can test how far educational selection specifically is in fact positively associated with those characteristics which it is commonly understood to represent, i.e. better cognitive and non-cognitive skills, more advantaged social networks, and better health.

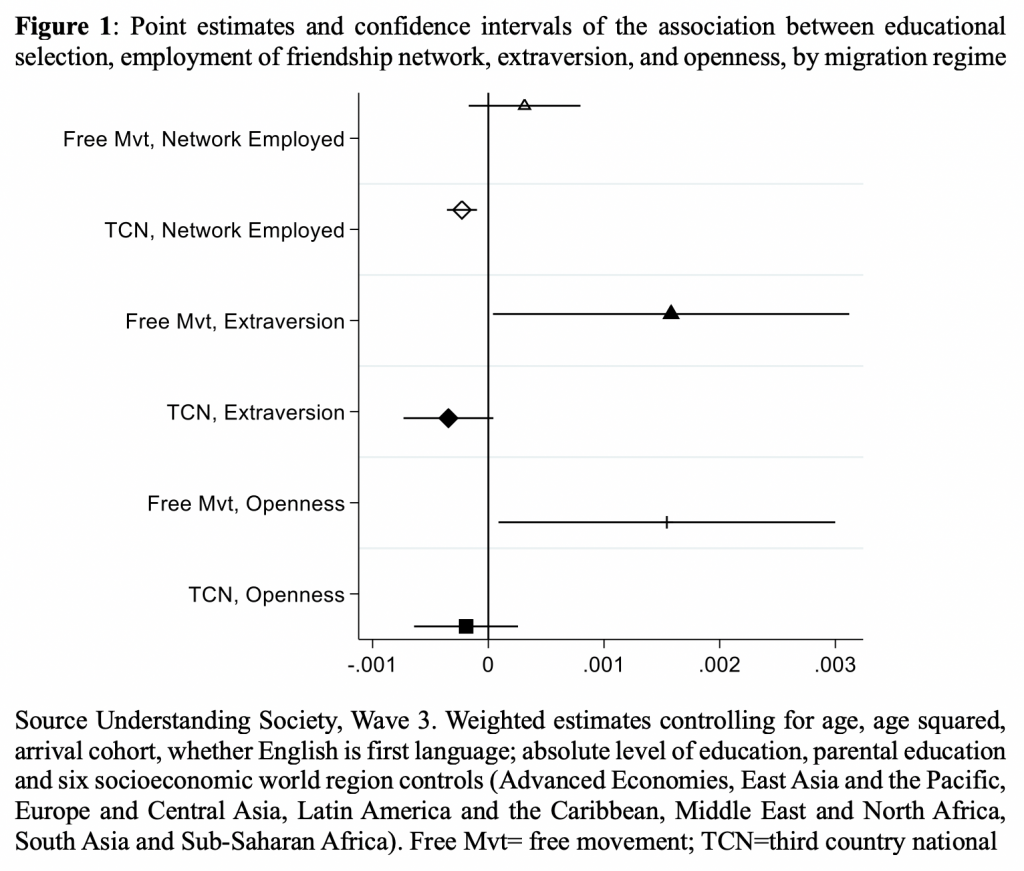

Surprisingly, we find that educational selection is either not associated or is negatively associated with all these potential mechanisms that could lead to better labour market outcomes. Moreover, we find that the relationship tends to be more negative for those who did not immigrate under free movement. Even taking into account that free movement migrants to the UK tend to be from wealthier countries, we find that for those who face higher barriers to migration, being from the top of the distribution does not deliver the ‘extra’ skills and characteristics that we might expect.

Figure 1 shows the association between educational selection and extraversion, openness and having more friends with jobs – all skills and characteristics which should help in the UK labour market. Yet we see that a positive association between these and selection only holds for free movement migrants. A positive association between cognitive ability and educational selection was also found for free movement migrants but not third country nationals, though these effects did not differ across the two at traditionally levels of statistical significance.

These findings are further supported by analysis which shows that while educational attainment is associated with better labour market outcomes (whether pay, employment, or occupation), educational selection has no additional benefit or, indeed, has a negative impact on these labour market outcomes.

With the recent end of free movement, and the equalisation of immigration rules, migrants to the UK will all face a similar regime. Facilitating entry on observed resources such as education and income, will bring those who are generally successful and can expect to get returns to those advantages. But it cannot be assumed to translate into the ‘brightest and best’ on other, economically salient measures. Rather than promoting the entry of the most motivated and those positively selected in other dimensions, imposing barriers across the board may come at a cost of excluding those for whom somewhat easier access to migration would enable them to better exploit their typically unobserved advantages.

_____________________

Renee Luthra is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Essex.

Renee Luthra is Senior Lecturer in Sociology at the University of Essex.

Lucinda Platt is Professor of Social Policy and Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Lucinda Platt is Professor of Social Policy and Sociology at the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Photo by Michał Parzuchowski on Unsplash.