Twitter has been banned in Nigeria since 4 June, and the government has since issued directives to arrest anyone still using the social network. Vincent A. Obia, a PhD researcher at Birmingham City University, looks at the motivation behind the ban and how the situation might be resolved.

Twitter has been banned in Nigeria since 4 June, and the government has since issued directives to arrest anyone still using the social network. Vincent A. Obia, a PhD researcher at Birmingham City University, looks at the motivation behind the ban and how the situation might be resolved.

Two days after Twitter took action to remove President’s Muhammadu Buhari’s tweet, the Nigerian Ministry of Information and Culture released a statement on Twitter (interestingly) announcing the “indefinite” suspension of Twitter in the country.

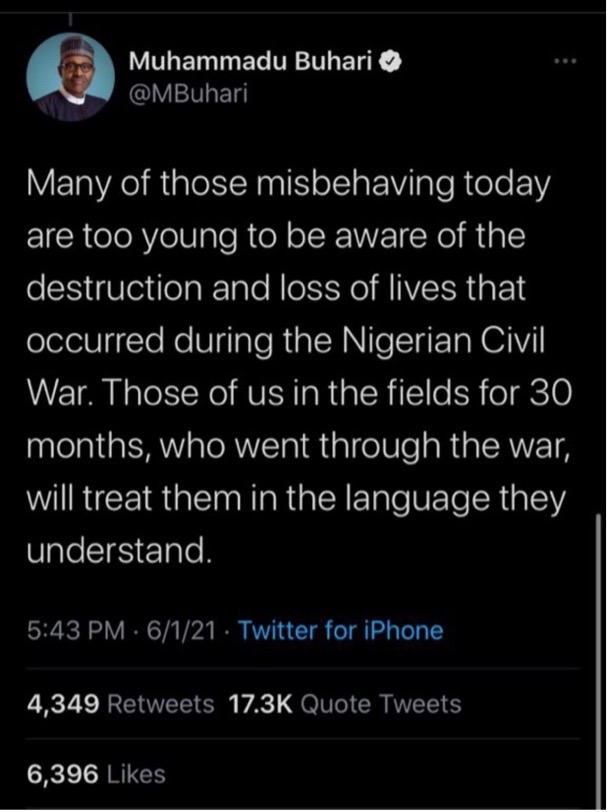

On 2 June, Twitter had taken down a post by Buhari and suspended his account for 12 hours, citing an infraction of its abusive behaviour policy. In the post, Buhari made reference to the destruction of government facilities in the country, linking this with the Nigeria-Biafra War of 1967-70. He also threatened to deal with “those misbehaving…in the language they understand”.

The President’s tweet came in the wake of Operation Restore Peace, a police campaign launched in May 2021 in the South-Eastern region to combat the rising level of arson and crime that the government blames on the banned secessionist Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and its military wing, the Eastern Security Network (ESN).

The President’s tweet came in the wake of Operation Restore Peace, a police campaign launched in May 2021 in the South-Eastern region to combat the rising level of arson and crime that the government blames on the banned secessionist Indigenous People of Biafra (IPOB) and its military wing, the Eastern Security Network (ESN).

This is the first time a social media ban of any kind has happened in Nigeria. According to NetBlocks Internet Observatory, the top four telecommunications operators (MTN, Airtel, Globacom & 9mobile) in the country have implemented the ban, blocking access to Twitter across Nigeria. However, VPNs which have been unaffected are being used by many to circumvent the ban. With the Twitter ban, Nigeria joins a notorious list of African countries including Uganda, Senegal and Congo where partial or total social media bans has been experimented with.

Why Twitter?

Reports show that Facebook also deleted a similar post on Buhari’s page for violating its Community Standard. In spite of this, Facebook has not been banned. There are suggestions that Facebook was spared in order not to make the link between the ban and the post deletion explicitly obvious. But to understand why Twitter has been specifically targeted, there is a need to recognise the platform’s socio-political role in Nigeria in recent times.

For instance, in his comment on the Twitter ban, presidential spokesman Garba Shehu said the move was taken not just because of the deletion of Buhari’s tweet, but also as a result of what he described as the “litany of problems” associated with the use of Twitter in Nigeria. Lai Mohammed, the information minister, has also said that “Twitter’s mission in Nigeria is very suspect”, particularly with regards to the October 2020 #EndSARS social movement against police brutality.

In essence, the government’s anger had been building against Twitter since the #EndSARS nationwide youth-led protests where the platform functioned as the primary medium used to channel anti-establishment rhetoric. I have written earlier about how Twitter served as the principal means of organising, co-ordinating and amplifying the movement. Figures by NOI polls show that the nearly 40 million Twitter users (approximately 20% of the population) in Nigeria engage in advocacy-related exchanges on the platform. Twitter is also seen by Nigerians as the most effective platform for activist discourse in terms of drawing attention to issues, communicating grievances, and influencing government policies, and so this move is not a surprise.

Twitter CEO, Jack Dorsey, also supported the #EndSARS protests, tweeting a branded hashtag for the movement and promoting donations to the cause. In its reaction to the current ban, Twitter further introduced the #KeepitOn branded hashtag, which has trended worldwide, representing Twitter users’ opposition to the ban in Nigeria.

Nigerian Twitter users tend to view the platform as their “ally:” a sort of oppositional tool that they deploy against the government. As Anke Wonneberger and colleagues note, Twitter’s architectural make-up of hashtags, @username and retweets is invaluable when it comes to hashtag activism, creating digital counter-publics and intensifying social movements. Therefore, in a country where the government’s inclination is to micro-manage the flow of information, the tendency is to see social media platforms through a “for/against us” prism. It seems that the government has placed Twitter in the “against” divide of the spectrum, and the ban only confirms this classification.

The Securitisation Argument

It is usual for bans like this to be justified on national security grounds. For instance, the statement announcing the Twitter ban said it was because use of the platform was “capable of undermining Nigeria’s corporate existence” – a pointer to the “national security” rationale. A case mentioned by Lai Mohammed was a tweet by Nnamdi Kanu, the IPOB leader, which was only deleted one day after the Twitter ban. In his tweets, Kanu has repeatedly claimed that Buhari, a Muslim Fulani from the North, is a clone and that he leads a “Fulanised” government of terrorists determined to annihilate Christian Igbos in the South-East.

As condemnable as Kanu’s claim and others like it may be, it hardly warrants a dictatorial stance on social media regulation. Hence, it is plausible to suggest that the Twitter ban and the general sentiment on social media regulation is motivated by the concept of the securitisation of speech acts. This is when an issue is grossly exaggerated above the realm of normal politics by a simple act of declaration (typically from a political actor), necessitating the use of extraordinary measures (that are usually not required), including placing limitations on otherwise inviolable rights such as freedom of expression.

In spite of this “national security” justification therefore, my suggestion is that social media is being targeted because the government wants to maintain unquestioned control over political expressions in the country. This kind of control has been exercised over the traditional media, particularly broadcasting where the National Broadcasting Commission (NBC) has imposed stringent rules on media outlets through the NBC Code. With social media platforms like Twitter the government has effectively lost this control over citizen political expression. The moves to regulate social media then points to an anxious government seeking to make a specific point about who has power over (online) information flow in Nigeria.

Where do we go from here?

The securitised approach to regulation presents new sets of challenges. On the one hand, it tends to target social media users directly, as evident in Nigeria’s 2019 Internet Falsehood Bill. This user-centred focus played out when the Attorney-General, Abubakar Malami, threatened to prosecute those who circumvent the Twitter ban by using VPNs, although there is no legal basis for the threat.

On the other hand, it seems platforms are being targeted through regulation, given the directive in the Twitter ban announcement that all social media platforms are to be licensed by the NBC.

Undoubtedly, the approaches used in Nigeria (and most of Africa) are problematic, even impractical. For instance, one struggles to see how the government can bring social media platforms under the exact same regulatory regime that exists for broadcasting. Also, attempting to formally regulate and sanction social media users directly with little input from platforms (as embodied in the Internet Falsehood Bill) present challenges – one of which is scale – that the government has likely not factored in.

There is then an urgent need for countries like Nigeria to consider alternative means of social media regulation, although the chances of this are slim. A multi-stakeholder framework will be the most ideal option considering the many actors involved in social media use and governance. Some approaches include Chris Marsden and Trisha Meyer’s co-regulatory approach, Caroline Are’s corpo-civic hybrid framework, and Natali Helberger and colleagues’ notion of cooperative responsibility.

Adopting any of these frameworks will require international alliances. This means Nigeria will need to exert a considerable amount of positive influence on platforms and the international community to shape regulatory outcomes. And for this to happen, countries like Nigeria must refrain from social media bans and other autocratic means of silencing online expression.

This article represents the views of the author, and not the position of the Media@LSE blog, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science.

Featured image: Photo by Brett Jordan on Unsplash