Indonesia and Peru are developing economies that have been severely hit by the pandemic. Despite being so geographically distant, culturally dissimilar and with markets of such different sizes, they share two key similarities from an international employment relations (IER) perspective:

- Both countries are witnessing an exponential rise in the development of the gig economy and digital platform jobs.

- An absence of regulation, and informality shroud both of their employment systems.

So where’s the opportunity during such a time of crisis?

As COVID-19 has proven to be a pivotal turning point in multiple ways, this case is no different. A more equitable labour relations system, we believe, is imperative in order to bridge social gaps for gig workers.

How do we achieve this?

By reinforcing the workers’ collective movements, rather than only dealing with the legal dichotomy of employee versus self-employed.

Similarity 1: A rapidly growing gig economy

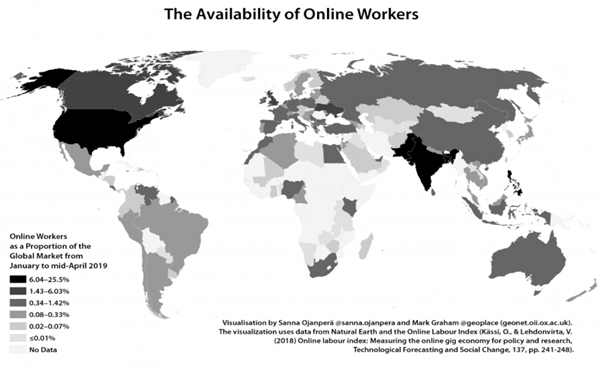

Emerging economies such as Indonesia and Peru are often perceived to constitute a lower concentration of gig workers compared to the global North, as shown in Figure 01. However, this is far from the truth.

Rather, the market for digital work in emerging countries is increasing rapidly. It is estimated that the use of digital labour platforms in the global South has significantly contributed to the annual growth rate of the gig economy, which stands at around 25% per year (Graham et al., 2017).

Given the COVID-19 crisis, the digital revolution and the gig economy is only expected to strengthen as such jobs are showing resilience (Ustek-Spilda et al., 2020).

Figure 01.

Source: https://geonet.oii.ox.ac.uk/blog/mapping-the-availability-of-online-labour-in-2019/

Peru

The number of Rappi riders have multiplied exponentially due to the;

- deactivation of multiple activities by the pandemic’s lockdown

- decline of formal employment

- ease of accessibility to platform work

Indonesia

The rapid rise of the online gig economy –especially in the creative, multimedia and transport industries – informs its immense potential in curbing unemployment. That is because this Internet-based form of work – which has been adopted rapidly in recent years to constitute one-third of Indonesia’s 127 million people, according to Bloomberg data (Unair, 2020) – remunerates gig workers with a reasonable salary (IDR 3.4 million), rendering it as a promising and competitive alternative to regular forms of employment.

Similarity 2: A legal void for gig workers

Gig workers’ classification as self-employed impacts their access to rights and benefits, as it makes it complex to identify an agent who could assume the role of a traditional employer. This could not only accentuate the precariousness of gig work but also trigger the creation of the collective movements and voice. Workers depend on gig platforms for their livelihoods, which is even more critical considering that many have to cover their operating costs with their income (Johnston & Land-Kazlauskas, 2018; Thompson, 2018; Jesnes, 2019).

Peru

This topic is not within any current legislative agenda, although recently the Ministry of Labour and Promotion of Employment have suggested their inclination to classify gig workers as 100% regular employees (MTPE, 2020). However, legislative ambiguity combined with the already high informality of the labour market in Latin America and the Caribbean – which according to the ILO a couple of years ago was around 53.1% (International Labour Organization, 2018) – increases the level of complexity for the structuring of a collective movement or voice.

Indonesia

The self-employed and freelance nature of gig work is characterised by increasing worker precarity and insecurity.Platforms do not accommodate workers’ aspirations, nor do they develop a pipeline for career progression especially for those in low-skill work. This reflects the further degradation of labour (Aneja and Mawii, 2020).

Opportunity: Glimpses of collective representation

Peru

Collective action and voice is founded on solidarity, and through them coordination, as well as complaints, recommendations and aid is provided. Although it is not frequent, the use of social media or online groups are useful to coordinate collective action demanding better labour treatment. Regarding the latter, in 2019 a group of riders gathered outside a well-known delivery App in Lima, claiming the company to back down on its commissions’ reduction (Cerna, 2019).

Collective coordination is useful for accidents or even when economic help is required because these virtual forums are used to gather the assistance needed. These cases show how, despite being faced with adverse conditions, gig workers’ collectives are making their way to weave networks based on solidarity and mutual aid (Graham, Hjorth, et al., 2017; Rosenblat, 2019; Cant, 2020).

Indonesia

Despite the fact that informal workers also constitute a high percentage (60%) of the total Indonesian workforce, platforms, driver communities, and unions affiliated with the platform economy, to some extent helps in preventing the deterioration of working conditions. For example, the company Go-Jek helps their drivers subscribe to the government health insurance programme, while at Grab Bike, workers are automatically enrolled in the government’s professional insurance programme (Alonso Soto, 2020).

Moreover, many gig workers have joined self-organised community organisations that function using mutual aid logic, that constitutes horizontal networks and strong social commitment.

This mutual aid-based approach, which builds on a long tradition of associational behaviour in Indonesia’s large informal sector, has facilitated high levels of membership and member participation in small, geographically based driver communities (Ford and Honan, 2019). This logic, however, is less well suited to;

- staging large-scale protests

- negotiating with the app-based transport companies

- engaging with the government

- overall affecting structural change (ibid), in comparison to unions

Key Takeaway:

As shown by the cases of Indonesia and Peru, reinforcing large-scale collective representation for gig economy workers is a critical starting point, if an equitable labour relations systems for gig workers is to be achieved in the years to come. Specifically, a mutual aid approach could serve as a base for collective representation in gig workers’ challenge for improved working conditions (Ford and Hanan, 2019).

However, such everyday forms of collectivism must be supplemented by unions and other large-scale organisations to pose a strong challenge to the power of their pseudo-employers, in search of improved labour conditions.

It is also critical that such organisations and collective movements embrace the importance of educating and training informal workers, to develop their economic potential to engage productively, not only in informal gig work, but gradually in formal work as well (Palmer, 2008).

References:

Aloisi, A. (2019). Negotiating the Digital Transformation of Work: Non-Standard Workers’ Voice, Collective Rights and Mobilisation Practices in the Platform Economy. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3404990

Alonso Soto, D. (2020), “Technology and the future of work in emerging economies: What is different”, OECD Social, Employment and Migration Working Papers, No. 236, OECD Publishing, Paris,

Amaral, N., Azuara, O., Gonzalez, S., Ospino, C., Pages, C., Rucci, G., & Torres, J. (2019). El futuro del trabajo en America Latina y el Caribe.

Aneja, U., & Mawii, Z. (2020). Strengthening labor protections for 21st century workers. Global Solutions Journal, (5). Retrieved from https://www.global-solutions-initiative.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/GSJ5_Aneja_Zothan.pdf

Cant, C. (2020). Riding for Deliveroo: Resistance in the New Economy. Polity Press. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2019.0086

Cerna, D. (2019). “It was the first time that they saw a human face”: An interview with Alejandra Dinegro on the situation of platform workers in Peru, The Global Media Technologies and Cultures Lab (GMTaC). http://globalmedia.mit.edu/2019/11/15/it-was-the-first-time-that-they-saw-a-human-face-an-interview-with-alejandra-dinegro-on-the-situation-of-platform-workers-in-peru-by-diego-cerna-aragon/

De Stefano, V. (2016). The rise of the just-in-time workforce: On-demand work, crowdwork, and labor protection in the gig-economy. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal,. Comparative Labor Law & Policy Journal, 37(3), 471–504.

De Presno, J., Wahle, J. C., & Capoulat, G. (2019). The gig economy and regulatory uncertainties in Latin America. Global HR Lawyers – Ius Laboris. https://theword.iuslaboris.com/hrlaw/insights/latin-america-the-gig-economy-and-regulatory-uncertainties

Faisal, A.L., Sucahyo, G., Ruldeviyani, Y., Gandhi, A. (2019) “Discovering Indonesian Digital Workers in Online Gig Economy Platforms,” 2019 International Conference on Information and Communications Technology (ICOIACT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia pp. 554-559, doi: 10.1109/ICOIACT46704.2019.8938543.

Ford, M., & Honan, V. (2019). The limits of mutual aid: Emerging forms of collectivity among app-based transport workers in Indonesia. Journal Of Industrial Relations, 61(4), 528-548. doi: 10.1177/0022185619839428

Graham, M., Hjorth, I., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2017). Digital labour and development: impacts of global digital labour platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. Transfer, 23(2), 135–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/1024258916687250

Heeks, R. (2017). Decent Work and the Digital Gig Economy: A Developing Country Perspective on Employment Impacts and Standards in Online Outsourcing, Crowdwork, etc. In Development Informatics Working (Issue University of Manchester, p. 82). https://doi.org/10.1016/0736-5853(84)90003-0

Healy, J., Nicholson, D., & Pekarek, A. (2017). Should we take the gig economy seriously? Labour & Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work, 27(3), 232–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2017.1377048

Howcroft, D., & Bergvall-Kåreborn, B. (2019). A Typology of Crowdwork Platforms. Work, Employment and Society, 33(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017018760136

International Labour Organization (ILO). (2018). Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A statistical picture. In Document and Publications Production, Printing and Distribution Branch (PRODOC) of the ILO: Vol. Third Edit. https://doi.org/10.1179/bac.2003.28.1.018

Jesnes, K. (2019). Employment Models of Platform Companies in Norway: A Distinctive Approach? Nordic Journal of Working Life Studies, 9(53). https://doi.org/10.18291/njwls.v9is6.114691

Johnston, H., & Land-Kazlauskas, C. (2018). Organizing on-demand: Representation, voice, and collective bargaining in the gig economy. Conditions of Work and Employment Series – ILO, 94, 54. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.12235.90400

Kässi, O., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2018). Online labour index: Measuring the online gig economy for policy and research. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 137(July), 241–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2018.07.056

Lehdonvirta, V. (2016). Algorithms that Divide and Unite: Delocalisation, Identity and Collective Action in ‘Microwork.’ In Space, Place and Global Digital Work (pp. 53–80). https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-48087-3_4

Makó, C., Illéssy, M., & Nosratabadi, S. (2020). Emerging Platform Work in Europe : Hungary in Cross-country Comparison. European Journal of Workplace Innovation Introduction, 5(2), 147–172.

MTPE. (2020). Informe final de grupo de trabajo de naturaleza temporal que tiene por objeto analizar la problemática sobre las condiciones de empleo de las personas que prestar servicios en plataformas digitales y plantear recomendaciones sobre la misma.

OECD. (2019). Negotiating Our Way Up – Collective Bargaining in a Changing World of Work. https://doi.org/10.1787/1fd2da34-en

Palmer, R., (2008). Meeting the Basic Learning Needs in the Informal Sector. Integrating Education and Training for Decent Work, Empowerment and Citizenship. Compare, 38(1), pp.125-149.

Pieter de Groen, W., Kilhoffer, Z., Lenaerts, K., & Mandl, I. (2018). Employment and working conditions of selected types of platform work. https://doi.org/10.2806/42948

Rosenblat, A. (2019). Uberland: How algorithms are rewriting the rules of work. In Uberland: How Algorithms are Rewriting the Rules of Work. University of California Press. https://doi.org/10.1177/0094306120915912jj

Schmidt, F. A. (2017). Digital Labour Markets in the Platform Economy. Division for Economic and Social Policy, 1–30. http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/wiso/13164.pdf

Sinatra, M. (2019). Riding the Gojek wave amid litmus test of perceptions. Retrieved 4 October 2020, from https://www.nst.com.my/opinion/columnists/2019/09/520413/riding-gojek-wave-amid-litmus-test-perceptions

Taylor, M., Marsh, G., Nicol, D., & Broadbent, P. (2017). Good Work: The Taylor Review of Modern Working Practices (Issue July). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102157

Thompson, B. Y. (2018). Digital Nomads: Employment in the Online Gig Economy. Glocalism: Journal of Culture, Politics and Innovation, 1, 1–26. https://doi.org/10.12893/gjcpi.2018.1.11

Ustek-Spilda, F., Heeks, R., Graham, M., Bertolini, A., Katta, S., Fredman, S., Howson, K., Ferrari, F., Neerukonda, M., Taduri, P., Badger, A., & Salem, N. (2020). How is the platform economy responding to COVID-19 ? Open Democracy. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/oureconomy/how-platform-economy-responding-covid-19/

Learn more about our MSc Human Resources and Organisations programme