From interviews to Instagram, how did we engage students in the evaluation of Clement House?

This article is one of three blog posts on the newly refurbished learning spaces in Clement House. It is written by Emma Wilson, Graduate Intern for LTI. You can find her on Twitter (@MindfulEm). For more information about the Clement House evaluation, please take a look at our final report.

Working with students as partners in the development of their university experience should form an integral part of any institution’s set of policies. However, securing a sufficient level of student engagement, which is also meaningful, poses a challenge across the sector.

Within the evaluation process for Clement House, we have been keen to utilise a wide array of communication channels – including some innovative new approaches which have involved social media. By complimenting the old and new, our mixed method approach to data collection has secured the involvement of 196 students. In addition, we carried out 67 non-participant observation; as such, the Clement House evaluation benefited from 263 pieces of data for analysis.

How did we publicise the work and recruit volunteers?

Put simply: targeted and personalised communications. Which departments are the most active users of Clement House? Where are students most likely to pay attention to posters on the wall? What incentives would attract students to participate? If students want to get involved, how would they like to do so? With the never-ending stream of emails, how do we know which will be paid most attention by students, and what are the alternative channels of communication?

By taking the time to consider the above, it is far more probable that students will show a willingness to engage themselves in a project evaluation.

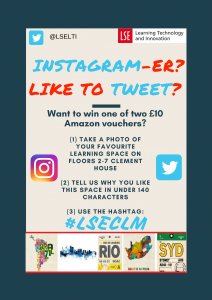

The use of visual communications has been a core component of this project evaluation. Posters were visible in strategic locations throughout the project, whereby a QR code and bespoke hashtag was used (where applicable). These posters were displayed across all floors of the Student Union’s building, and electronic versions were broadcast in the library and Clement House (including the International Relations Department which is based there).

Poster One: Seeking student engagement in an online survey

Poster Two: Seeking student engagement in a social media competition

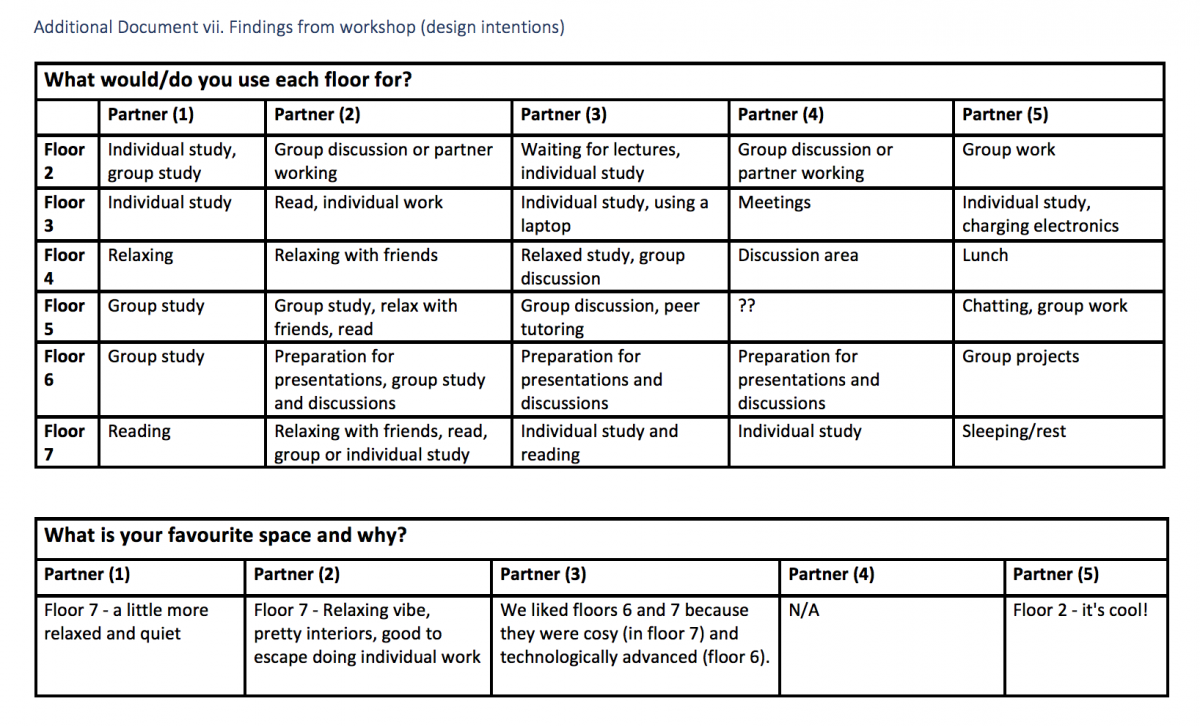

Findings based on method of engagement

We created an online and paper version of a survey. The questions were identical although the online survey provided space to make any additional comments. We received 55 responses to the survey in paper format, and 45 via the online survey. The social media campaign ran outside of term time, for a shorter period of time (2.5 weeks), and received 12 responses. This data was supplemented by 74 structured interviews of 1-3 minutes that were carried out during the non-participant observations (of which 67 were carried out across 4 weeks).

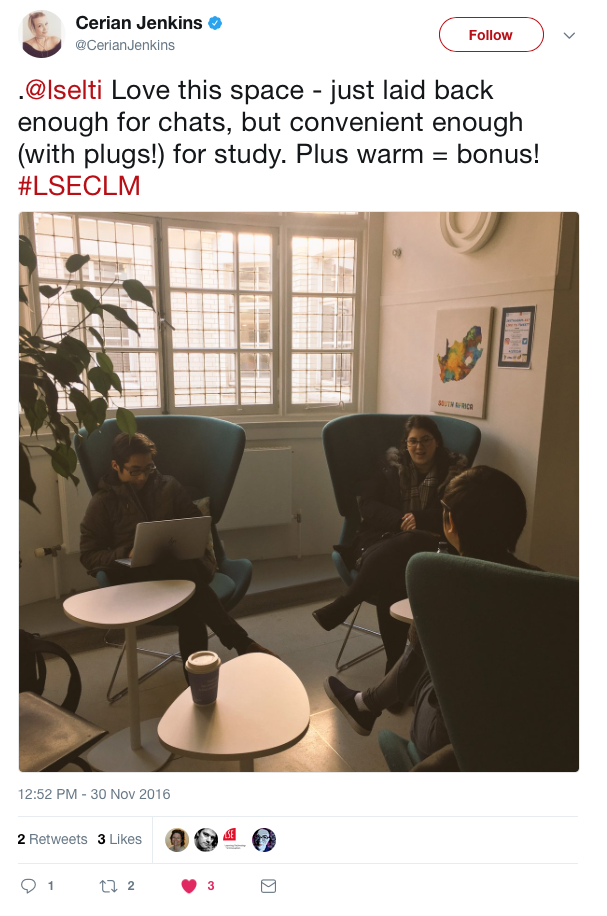

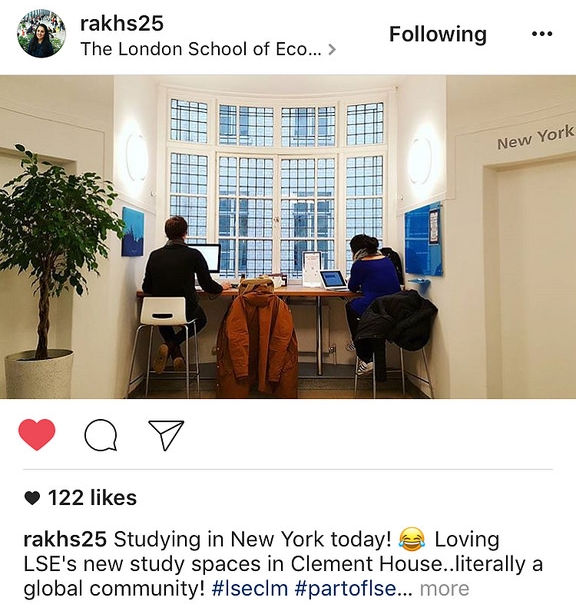

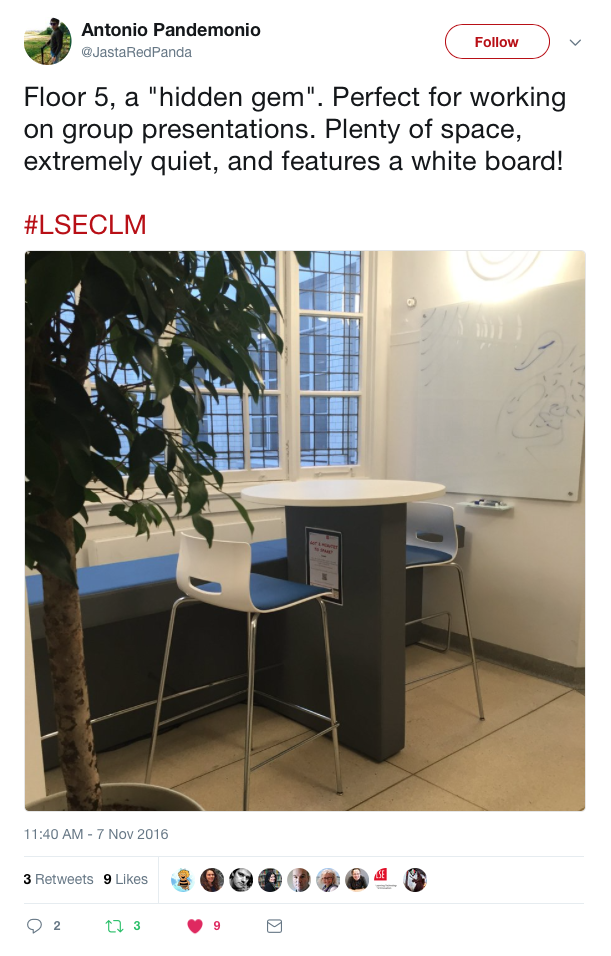

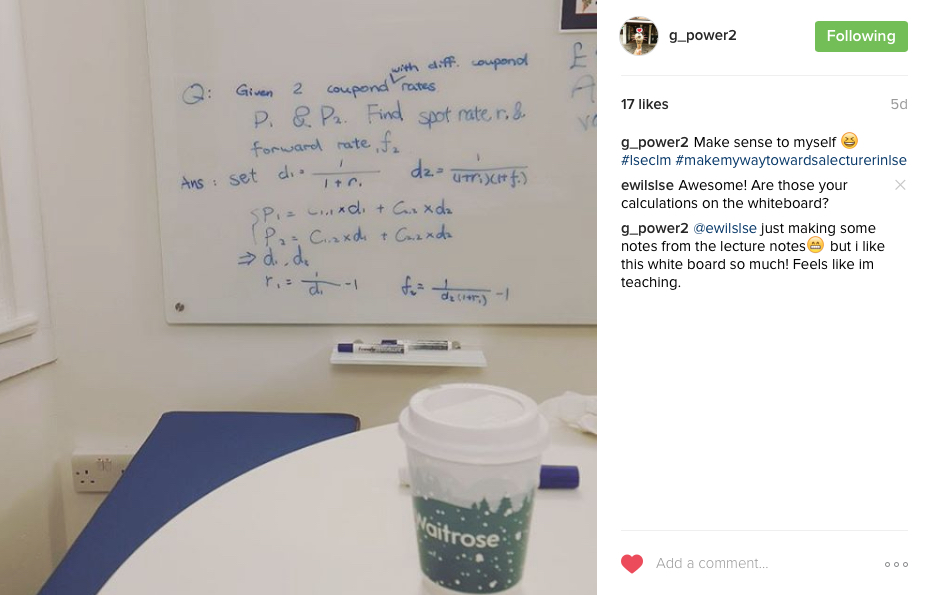

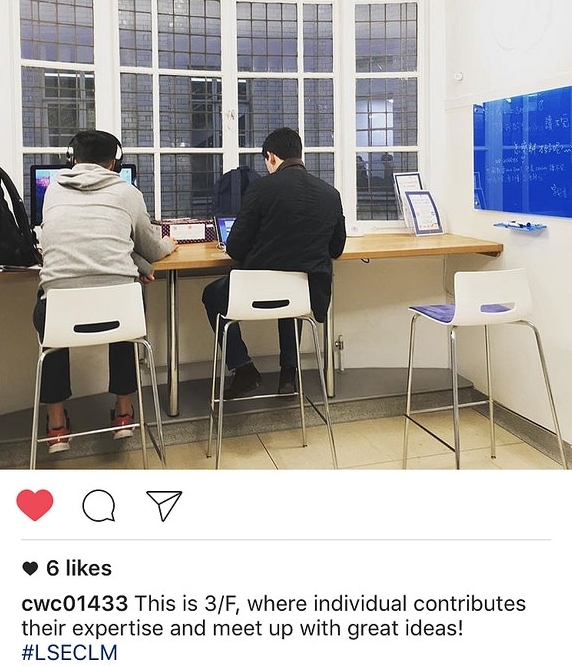

Key findings from the evaluation can be found in our report and in our other blog posts (see links). We have also drawn together a selection of Tweets and Instagram responses and displayed them as a collection on Storify. A sample of Tweets and Instagram posts can also be viewed in the slideshow below.

Sample of Tweets and Instagram posts

What lessons have we learned?

A mixed approach to data collection enabled us to find a balance between a purely qualitative or quantitative approach. Whilst interviews provide an opportunity to understand how and why a student feels a certain way, the use of close-ended survey questions ensures a certain amount of objectivity in particular instances. For example, in the survey it was useful to provide students with four options when asked about the purpose of their visit to the learning space. This allowed comparability across floors. However, it was the richness of data collected from the subsequent open-ended questions (whether in the interview or survey) that enabled us to fully understand the reason why a student feels a certain way.

With a mixed method approach, it is important to ensure consistency of methodology across data collection methods. Do you have the same questions for the paper and online versions of the survey? If not, why not? How can any differences be taken into account?

Looking ahead, I would be keen to encourage the future use of a mixed methods approach to data collection. If carrying out a social media campaign, it is important to consider the time of year in which the campaign in launched; if it’s outside of academic teaching, many students will not be on campus, and you will have to place a greater reliance on online promotion. It is also useful to check whether the university is conducting any other surveys – such as the NSS or end-of-year departmental feedback questionnaires – to ensure that students are not overwhelmed by the number of surveys they are being asked to complete.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution to successful student engagement and it is important to consider the following:

- Know your audience

- Who are you trying to secure engagement from? (Students? If so, are you seeking feedback from those in a particular department or academic year?)

- When might they be most willing to get involved? (Whilst waiting for their next class? As a break or distraction from revision? During a particular event?)

- What are the incentives for them to get involved? (Focus on your language – emphasise the power of the student voice in contributing towards policy change; offer students the chance to win a voucher; if running a workshop, say that it’s an opportunity to network with peers and even make new friends)

- Think about how the ways in which they can get involved

- Will canvassing a busy student before class necessarily be more effective than a survey that can be filled out in their own time?

- Is the university keen to promote engagement through Instagram or Snapchat? Can your project also utilise these platforms?

- Connect with colleagues across departments and student groups or societies

- Partnerships and collaborative working are great ways to contact groups of students who might be harder to reach.

- Think about your audience – who are they likely to be in contact with? If students, do they have a student representative for their academic course?

- Make contact with the university’s Student Union (SU); for example, their student engagement and communications officer. Getting some publicity on their website, social media feeds and newsletters is great for exposure. Asking to place posters around the SU building is a good way to reach more students.

Ultimately, this project unveiled a positive message: students are keen to get involved in sharing their views on the teaching and learning experience at LSE.

Don’t be scared to pilot a new approach to student engagement. Understand your audience, think about how they interact in the university community, and take advantage of the new channels of communication. Over the next few years, we are likely to witness a changing landscape in higher education as Generation Z bring to their university a whole set of new expectations, skills and approaches to life in an ever-evolving digital environment. It is an exciting time for universities to engage with students and discuss the potential and opportunities for the future of higher education. By approaching engagement in a creative way, we are more likely to kickstart a widespread conversation across the entire learning community.

Links

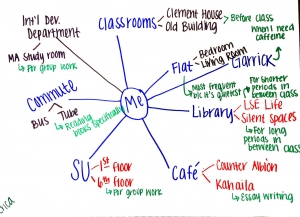

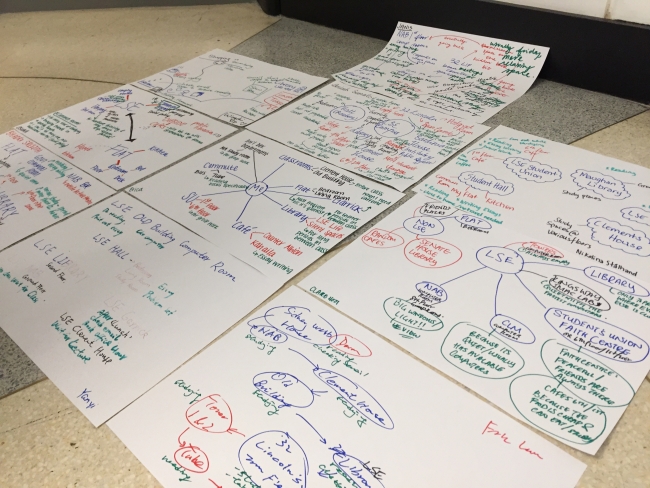

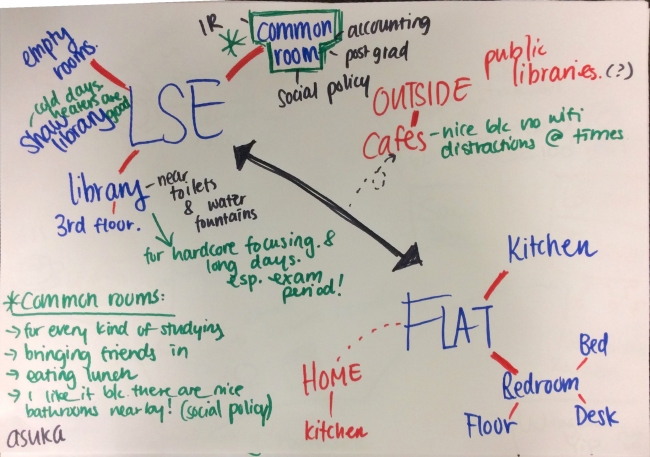

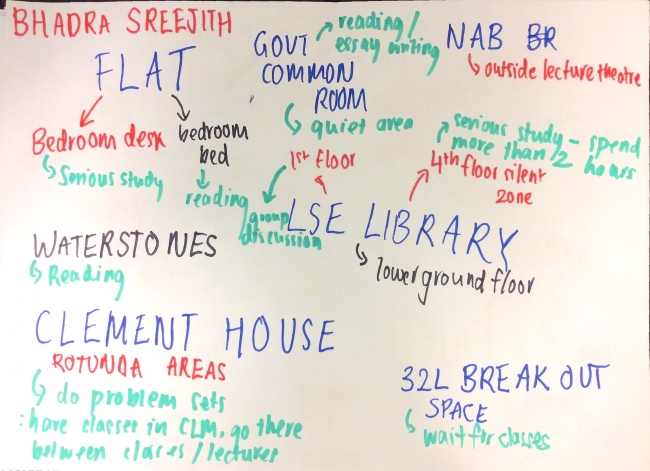

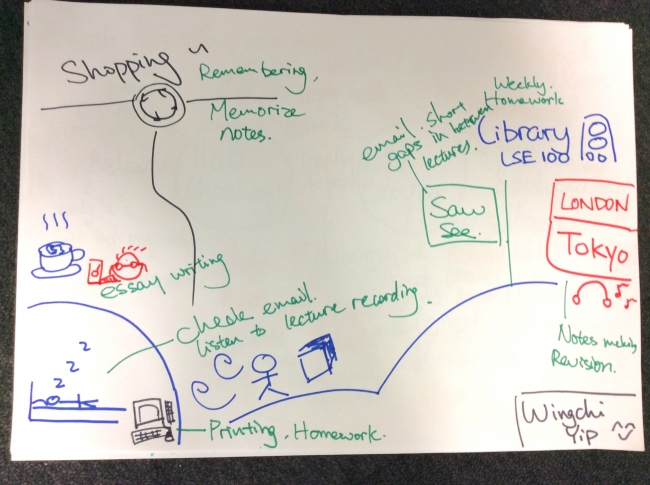

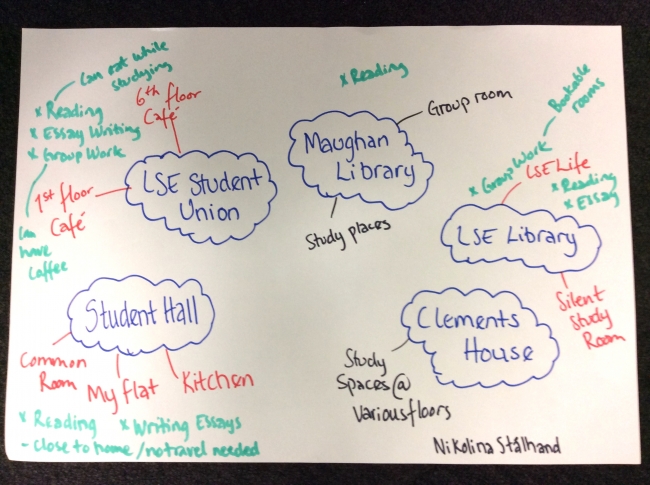

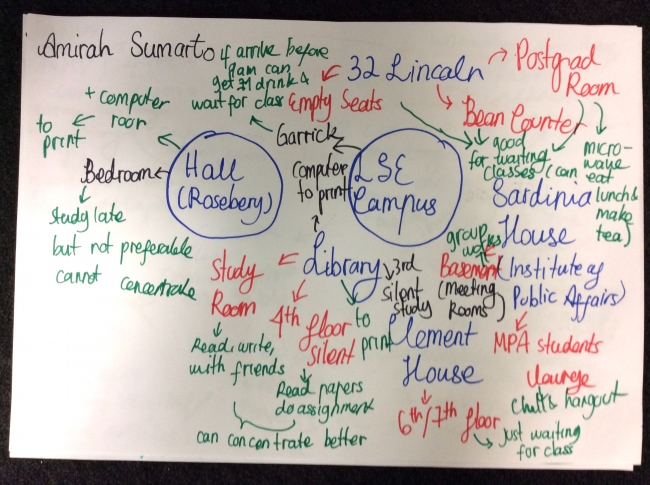

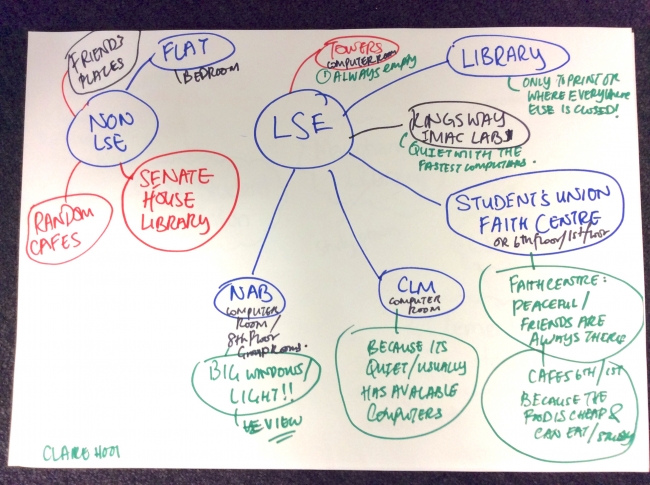

attitudes and preferences of LSE students using informal learning spaces such as those within the Clement House rotunda. Specifically, to better understand how, what, when, where and why students use particular learning spaces.

attitudes and preferences of LSE students using informal learning spaces such as those within the Clement House rotunda. Specifically, to better understand how, what, when, where and why students use particular learning spaces.