What stands at the roots of the current Macedonian crisis? Thibault Boutherin takes a bird’s eye view and locates the four main problems of the country – four ‘plagues’, he calls them – in the lack of rule of law, in the ever-increasing ethnic divide that is being exploited by the political parties to their advantage, in the shady practices that have left space for external players to enter the Balkan chessboard, and in the loss of influence of the European Union.

What stands at the roots of the current Macedonian crisis? Thibault Boutherin takes a bird’s eye view and locates the four main problems of the country – four ‘plagues’, he calls them – in the lack of rule of law, in the ever-increasing ethnic divide that is being exploited by the political parties to their advantage, in the shady practices that have left space for external players to enter the Balkan chessboard, and in the loss of influence of the European Union.

The ever-growing tensions in Macedonia have been sending serious warnings to its Western Balkan neighbours and Europe for several years, gaining only little attention and weak reactions. From a rather discreet country peacefully born in the aftermath of Yugoslavia’s collapse, Macedonia has become one of the most sensitive cases of the region.

In May 2015, the danger seemed closer than ever: fights between the police and a group of alleged ‘terrorists’ killed 22 people in Kumanovo, while in Skopje massive demonstrations of both opponents and supporters of the government laid bare the level of political, social and ethnic strain dividing the country. Even if this happened to be nothing but another alarm bell ringing to no serious outcome, it is the symptom of a very worrying situation, whose consequences could in the future be felt not only throughout the region but, potentially, throughout the continent, as it happened in the recent past. These events seem to be at once the cause and the result of four main problems – four ‘plagues’ – which are affecting Macedonia and its relations with the EU, and have turned the country into a “pressure cooker”.

Plague 1: Weak democracy and rule of law

The first so-called plague that the country is suffering from concerns its generally degraded political setting: the state is weak, both democracy and rule of law are challenged. Macedonia appears to be stuck in what one could label a “permanent crisis”. Since the 2001 crisis and the constitutional changes made by the Ohrid agreement, the legislative work in Macedonia has been a row of boycotts by the opposition parties, just as in 2007, 2008, 2011 and since 2014. The sincerity of each election has also been contested.

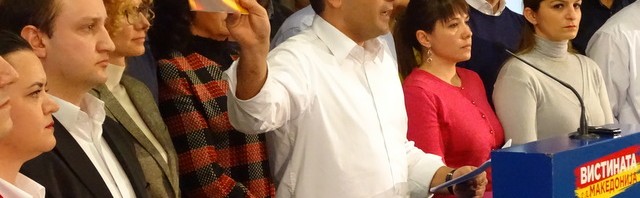

This created a situation where the laws are designed and voted for only by the ruling majority, without much contribution from the minority parties, thus weakening the national legal framework and, hence, the state itself. The two main Macedonian-Slav parties (the ruling VMRO-DPMNE, in power since 2006, and its main opponent the SDSM), along with their Albanian counterparts, have created a political deadlock. These divisions have been mirrored at the recent demonstrations, during which government opponents and supporters alternated themselves.

These divisions have progressively led parties to adopt a ‘diehard’ positioning, in a climate where appeased debates, negotiations and compromises, so dear to democracy, are not possible. The mutual accusations of corruption, nepotism and misuse of the state apparatus have taken the political discourse away from the general interest and from discussions on the future of the country.

In January 2015, the SDSM leader Zoran Zaev disclosed a huge scandal of wiretapping allegedly undertaken by the government, targeting up to 20,000 people including opponents, journalists, NGOs, etc. This also brought to light mass-scale corruption scandals and the suspicion of governmental influence in a quintuple-murder case for which 6 Albanians where convicted. These revelations were at the core of the demonstrations against the government earlier this month, followed by another one, of similar size, in support of Gruevski.

In addition, freedom of press appears to be in serious downfall; in its report on the 2011 legislative elections, the OSCE concluded that “the majority of broadcasters follow partisan editorial policies, frequently blending fact and editorial comment”. The NGO Reporters Without Borders ranked the country at the 117th position (out of 180) for media freedom, and in May 2015 the Journalists’ association ZNM denounced the millions which the government spent on television and newspaper advertisements in order to secure the support of those media.

Plague 2: Endemic tensions between ethnic groups

Another major issue are the ethnic divisions of the country. Tensions have been increasing, and violent outbursts occur on a regular basis. The rights of the 26 Macedonian minorities have arguably improved since 1992, but the ill feelings and the antagonisms are still considerable – especially between the Macedonian-Slav majority and the sizeable Albanian minority. Young generations are growing ever more segregated: they do not attend the same schools, do not speak the same language.

There is, as a matter of fact, a lack of will on both sides. The political representations of communities only go along ethnic lines, encouraging clientelism and making the cohesion of the nationalities under one Macedonian citizenship impossible in practical terms. Parties make a very opportunistic use of power, fighting for the monopoly of their own national representation. The current government makes a clear use of the tensions as a diversion strategy: a scenario that is likely to have occurred in Kumanovo. Both sides recognise the benefits of maintaining the status quo or of escalating tensions.

Plague 3: An economic and diplomatic grey zone

This unhealthy environment is a particularly apt humus for another plague that the whole region is acquainted with, though at different degrees of gravity: Macedonia’s ‘reputation’ as an organised crime, smuggling and trafficking regional centre has risen in recent years. As if it weren’t enough, Gruevski announced his plan to make out of his country a fiscal haven, with “the lowest tax rate of Europe” – while the EU is at the same time supposed to be fighting against fiscal evasion.

The PM’s project delighted many tax-dodgers and shady dealers, but also countries with geopolitical aims that are antagonistic to the EU’s interests. These countries are willing to take part in the game while fortifying their own influence in a growingly strategic region for the energetic procurement of Western Europe: China is building motorways while Russia is becoming a more active stakeholder, supporting Gruevski against Albanian “acts of terrorism” and “Western intrusion”. Replying to the attacks against the wire-tapping scandal, the Prime Minister has criticised the attempt of “some Western country’s intelligence service to topple down the government”, echoing the position the Kremlin took to explain the EuroMaïdan protests. Europeans, numbed by a long period of peace and prosperity in spite of the recent events in Ukraine, might have developed a blind spot for potential conflicts. The same, however, is not true for Russia and China: their actions indicate that Macedonia is becoming yet another ground of rivalry in the globalised competition for geopolitical influence.

Plague 4: The progressive loss of influence of the EU

For years now, facing economic and institutional crisis, the EU’s institutions and its member-states have been almost entirely focused on their internal issues and challenges, giving very little attention to the Western Balkans (with the partial exception of Kosovo). The European Commission made it clear that there would be no further enlargement until the end of Juncker’s term, i.e. until 2019.

The three major issues described above were thus largely ignored by the Union. And yet, as the Balkans specialist Jacques Rupnik recently put it: “the EU’s responsibility is very considerable, because it made promises to Macedonia but did not keep them”. For a while now, Brussels’ lack of interest and encouragement has been seriously at risk of diverting any serious efforts of democratisation into more populist – and thus more immediately politically successful – manoeuvres. As it has been pointed out following the negative Progress Report, the EU has been losing influence as Macedonians are starting to give up on any prospects of an accession that seems now so far that it is almost starting to look impossible.

Some encouraging developments

Responding to the most recent events, EU officials have finally taken a proactive stance, seeking to facilitate a political solution.

On 2nd June, the EU Commissioner for Enlargement, Johannes Hahn, met with the parties’ leaders and with the US Ambassador in Skopje. An agreement to hold early elections was reached, due to take place in April 2016. The transition period – who will govern and with which priorities – remains, however, a question mark; though the EU may propose to start the screening of the acquis, which is the first step in the pre-accession process.

In spite of this positive move, reaching an overall agreement will not be without difficulties. And yet some observers, such as Erwan Fouéré, a former EU Special Representative in Macedonia who has been fiercely critical of the country’s political situation in the past, consider that these developments may be a chance for Macedonia. Fouéré remarked that the unprecedented unity across ethnic lines shown by Macedonian citizens during the demonstrations on May 17th and the emergence of a civil platform are encouraging signs.

Is the country actually on its way out of the crisis? It is certainly too soon to tell, and it will only depend on the will of its leaders and the efficiency and effectiveness of the EU actions. The next weeks will be, in that regard, absolutely decisive. Allowing a country at the EU’s doorstep to sink and wallow in its own struggles is not without danger for the Union itself: it affects the values at its very heart – unity over nationalism, peace and prosperity over chaos. The EU needs now to move with decision if it does not want to lose the only real antidote it possesses to tackle these ‘plagues’ – integration.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

___________________________

Thibault Boutherin is a Consultant in European Affairs, specialised in the Western Balkans. He graduated from the College of Europe (Warsaw) and Sciences Po (Paris) in European affairs. He regularly publishes articles and analyses about the region for the Robert Schuman Foundation, for Diplomatie Magazine and other outlets.

Regarding your “encouraging developments” section…I would argue that you pointed out the wrong things.

First, you should have pointed out that in no time since Macedonia’s independence have ethnic relations in the country been more favorable. The anti-government/anti-political system protests have brought together ethnic Macedonians and Albanians en masse (along with a lot of other minorities- Turks, Roma, Serbs, Bosnians, etc.). Something that is beautiful and shows signs of the plausibility of a multiethnic Macedonia.

Second, the political agreement which the party leaders and Johannes Hahn are working on regarding holding early elections before May 2016 simply doesn’t meet any of the clearly stated demands of the citizens that have come out to protest. The EU and political leaders in the country should give civil society and citizens a seat at the negotiating table (which is also unfortunately being held behind closed doors rather than being open to the public). What is the point of agreeing to something that only helps the political elite partially “solve” their issues while utterly disregarding the demands of the thousands that have taken to the streets?

The protests will continue whether there are plans for elections or not. The people want systematic political and societal change…not a change in leadership.

Noticeably missing from this article is mention of the “minor” point of Skopje’s bizarre attempt to re frame themselves from Slavs into “ancient Macedonians” and irredentism (as Greece warned against 20 ago… but was ridiculed by alleged experts)

One wonders how the PM of the Former French Possession of Britain would react if everyone recognized western France as “Republic of England”… their French language as “English”… as they built giant statues to King Henry… and openly encouraged United England. We suspect names would matter then.

Enough is enough. No excused left for evasions of Skopje’s apologists. Greece must change its foreign policy to include hostility to not only VMRO but to foreign any nationalists that aid and abet Skopje (effectively now morally complicit in their subtle attempts to ethnic cleanse Greeks to hide their mistake of calling former Yugoslavians “Macedonians”)

….

Gentlemen, the key to existence of Macedonia is in the hands of Kosovo Albanians. The key to actually Serb dominated northern Kosovo is in he hands of Macedonian Albanians. Currently Kosovo supports unified Macedonia so do the leaders of Macedonian Albanians. If one meter of these borders change the game is on and believe me the Albanian nation will not go out as losers from this one. It as amout territory.