The most shocking result of the Moldovan elections has been the rise of the Socialist Party, closely associated with Russia. “It would be incorrect to see them as Russian stooges, opportunists, or as old faces under a new banner. Instead, their support has come from those concerned about corruption, poverty, Europeanisation and a growing dissatisfaction with Moldova’s Communist Party’s leadership”, argue Daniel Brett and Eleanor Knott.

The most shocking result of the Moldovan elections has been the rise of the Socialist Party, closely associated with Russia. “It would be incorrect to see them as Russian stooges, opportunists, or as old faces under a new banner. Instead, their support has come from those concerned about corruption, poverty, Europeanisation and a growing dissatisfaction with Moldova’s Communist Party’s leadership”, argue Daniel Brett and Eleanor Knott.

Pure democracy is three wolves and two sheep voting on what to eat for dinner.

Benjamin Franklin

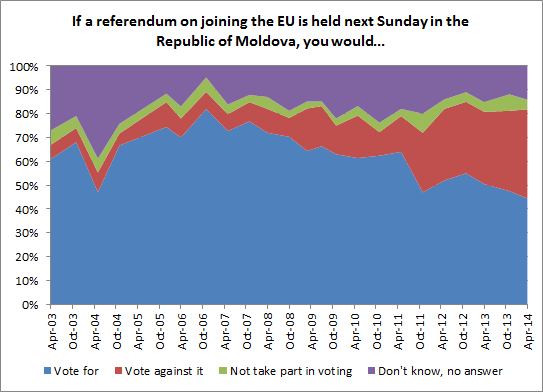

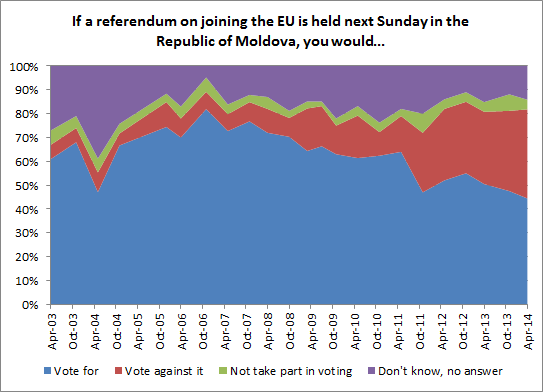

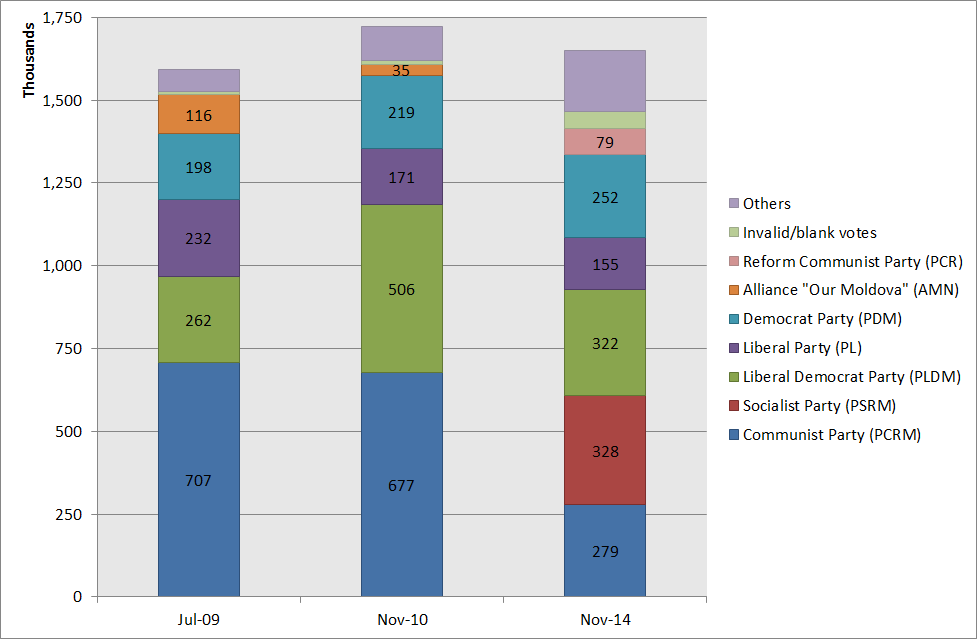

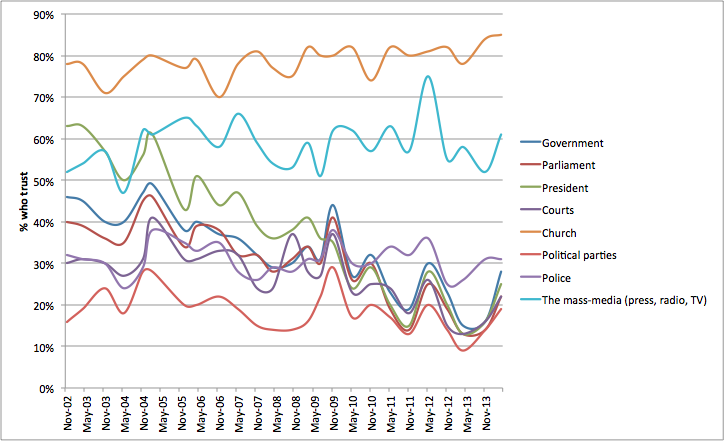

With Moldovan society split in half, as opinion polls show (Chart 1), it is no surprise that Moldova’s parliamentary elections, held on 30 November 2014, failed to produce a decisive mandate for Moldova’s seemingly zero-sum geopolitical direction. PSRM went from zero seats in the previous parliamentary elections, in 2010, to win the largest number of votes and seats in 2014. For the established parties this defeat came as a shock. The tripartite pro-European alliance, consisting of the Democrat Party (PDM), Liberal Democrat Party (PLMD) and Liberal Party (PL), still managed to gain sufficient seats to form a parliamentary majority, despite losing 9 seats since 2010. Secondly, Moldova’s Communist Party (PCRM) who have been the biggest party since 2001, lost 50% of their seats (from 42 to 21 seats) and about 400,000 voters since 2010.

The two real losers of Moldova’s elections are the most established and supported parties. Pro-European forces failed to win the hearts and minds of the electorate and to convince them of their progress, even in the shadow of some achievements, such as EU visa liberalisation (April 2014) and signing of the EU Association Agreement (June 2014). However PLDM, the biggest and most moderate party of the pro-European alliance, did far worse than other parties in the alliance (losing 9 seats, while PDM gained 4 while PL gained 1 seat). Secondly, PCRM saw their support cut in half, with defections both of voters, national and local level politicians to PSRM. PCRM has been plagued by the persistence of Voronin as leader and a lack of new blood rising up the ranks. PCRM may then not recover from this blow, with PSRM continuing to gain from those apathetic or antagonistic towards the pro-European parties.

Who are the Socialists (PSRM)?

The biggest shock of the election was the success of the PSRM. Despite polling in single digits prior to the election, they became the single largest party. Although the party formed in 1997, PSRM had not stood in elections since 2005. In 2011, a number of disaffected but prominent PCRM politicians joined the party including former Prime Minister Zinaida Greceanîi, and former Finance Minister Igor Dodon. Politically, Greceanîi can best be described as neo-Soviet. Shortly before leaving PCRM, Dodon proposed reforms for the party, warning that without modernisation it would die electorally. It would be incorrect to see them as Russian stooges, opportunists, or as old faces under a new banner. Instead their support has come from those concerned about corruption, poverty and Europeanisation, but also those who are dissatisfied with the direction and stagnation of PCRM (and Moldova) under Voronin.

In the three elections since the 2009 “Twitter Revolution”, which ousted the PCRM government (2001-2009), there has not been a consolidation of the party system towards fewer parties. The number of parties contesting elections actually increased from 8 in July 2009, to 20 parties in 2010 and 19 independent candidates (despite mergers of parties with PLDM and PL). By 2014, 20 parties stood for election as well as 4 independent candidates and 1 electoral bloc. More interesting is that only 6 parties have stood in all elections since 2009, while of the 12 new parties in 2010, only 3 re-appeared in 2014. Meanwhile activists, such as Oleg Brega, though unable to garner enough support for the 2% threshold, were still able to attract significant support (14,085 votes, 0.9%).

However barriers to entry, from being on the ballot to being in parliament, remain high. Electoral thresholds which were lowered after 2009 (from 6% to 4%) have, since 2013, been raised back to 6%, just as they were during Voronin/PCRM’s term. Whether to curb, ahead of time, the potential threat posed by PSRM, it had the effect of preventing the Communist Reform Party (PCR) from entering parliament. An alternative interpretation, suggested by Dorin Chirtoaca, the mayor of Chisinau and senior PL figure, is that PCR was set up deliberately to confuse voters and, hence, reduce the vote of PCRM.

Both of these possibilities demonstrate a desire for pro-European parties to play, legally, with the limits of what is fair, to secure the best outcome for themselves at the expense of a clean election. Moreover they show a resistance to make Moldova’s political system more competitive, with Moldova having one of the higher PR thresholds (lower only than Iran, Turkey and Russia) and lowest conversion rates between votes won and seats allocated (according to Council of Europe recommendations). Since 2009, Moldova’s legislature has also changed the way votes to seats have been allocated: from the D’Hondt system (the most commonly used system in PR), which was seen to favour larger parties like PCRM, to the ‘equality system’ (or Robin Hood system) which favours seat allocation to smaller parties.

More than between Europe and Russia?

Analyses of Moldovan elections need therefore to go beyond the simple narrative of western media where elections are conceived as a referendum between Russia and Europe, and Moldova constructed as Ukraine in waiting. Nor should ethnic cleavages be framed as reinforcing this geopolitical binary because not everyone voting for PSRM is an elderly Russian peasant fearful of the decadent European Union. Indeed the new batch of PSRM deputies show the widest spread of ages: from those born in the 1930s to those in the 1990s.

Moreover the dichotomy between ‘left’ parties in Moldova as Pro-Russia and ‘right’ parties as pro-Europe does not fit reality. Instead, geopolitical orientation is just one axis upon which parties pivot, the second is social values, and the third is economic orientation. Parties tend to be dominated by charismatic and powerful leaders with strong local power bases and networks (e.g. parties do well in the home-towns of senior party figures). Policy, especially geopolitical and economic, tends to be defined by the leadership’s material interests and their networks. Discourse tends to shift in search of an electorate to enable the party to gain votes in order to achieve those aims, thus parties such as the PCRM have shifted from Pro-Russian, to Pro-European attitudes and back again with the interests of the elite rather than the voters.

Europeanisation is therefore not just a geopolitical issue, but also a cultural and economic issue. Thus, those who vote for parties that advocate closer ties with Russia are mobilised around a variety of discourses – the threat of war and instability, the perception of Western culture as decadent and degenerate, as well as the fear that EU membership will not improve their economic lives but make them worse.

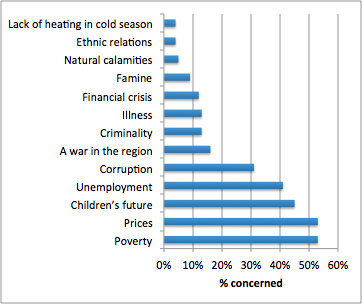

Moldovan society is also divided by far more than ethnicity and geopolitics, with stark differences between the rich and everyone else, between generations, and between rural and urban. It is these socioeconomic questions and divisions, as well as low and declining trust in political institutions (Chart 3) and high perceptions of corruption, in particular in political institutions, which remain key problems. While the electorate continue to perceive that deep socioeconomic inequalities remain (Chart 4), the political elite appears disinterested to work on improving the welfare of ordinary Moldovans. And this is perhaps where Moldova is most divided, between the political class and electorate, in particular between a pro-European political class who see Europeanisation as a panacea for Moldova – if Moldova could only get on a European track, then all other problems will be fixed – and an electorate who remain unconvinced both by this track and by its salvationist potential.

Corruption not Europeanisation

What is most concerning about the 2014 Moldovan elections is the extent to which the pro-European parties are unwilling to play a clean race, such as modifying electoral thresholds to restrain who can enter parliament. Secondly, is the lack of transparency in politics, for example in determining how many polling stations are opened abroad, allowing Moldovan authorities to increase the number of polling stations in the EU while contributing to ‘public perceptions that the government sought to discourage voting in the Russian Federation’ according to the OSCE, for the high number of Moldovan diaspora residing there. This will continue to be a hard fought battle in the next parliamentary term between the pro-European parties and PSRM, who are now appealing for a recount of diaspora votes.

The Moldovan political system continues to be plagued by over-partisan politics and institutional overreach. Moldova’s constitutional court is pro-European both as a highly partisan and highly politicised institution, ruling in October that only a pro-European path for Moldova would be legal. The constitutional court then ruled, days before the elections, to suspend the right of Patria (Homeland), from running in the elections, because they had received evidence of foreign funding. Patria, and its frontman Renato Usatîi, made headlines as a recent wealthy returnee from Moscow, alleging close ties to Russia.

As much as the allegation of funding may be true, as may be Patria’s ties to criminal military gangs, the issue remains that pro-European elite are willing to use asymmetrical justice to punish opponents and constrain electoral outcomes. Campaign financing is certainly an issue in Moldovan elections, but as the Council of Europe have argued, the Moldovan authorities are far from having a transparent and accountable handling of these wider issues. The Moldovan judicial and electoral commission need to do far more than selective partisan enforcement of the electoral code. These duplicitous tactics are also paradoxical. Firstly, they likely cemented PSRM’s vote by picking up those disaffected by this ruling, rather than scaring pro-Europeans into mobilising to oppose the pro-Russian parties. Secondly, they supply Russia with more material to discredit Moldova’s elections and the desire for pro-European parties to steer Moldova towards the EU (and away from Russia).

The Moldovan electorate are likely less concerned with the running of the electoral system than they are with important socio-economic issues and corruption. However, the willingness of the pro-European parties to play a dirty game, presents a bigger problem. It demonstrates that the Moldovan political class are no nearer to reforming themselves, away from “hungry wolves” seeking to use power and privilege for immunity, towards greater transparency and accountability. This remains at the heart of debates concerning the unmet promises of the pro-European alliance, since they took office in 2009 in what was seen as a critical juncture, not just for Moldova’s geopolitical orientation, but also in terms of politics and socioeconomic questions.

We therefore need to go deeper than viewing Moldovan politics and these elections as a simple zero-sum ethnic or geopolitical cleavage between Russia and Europe. If democracy is to become consolidated in Moldova, then the political elite must confront the problems of inequality, corruption, and the absence of agency and trust, and move beyond their fixations with the “civilizational choices” (as Iurie Lenca, current Moldovan Prime Minister described) that Moldova faces.

Instead, the pro-European parties have to deal with domestic political problems of corruption, transparency and trust if they want to hold onto power. The EU can sign as many agreements with the Moldovan political elite as they like, but as long as the Moldovan political elite remains corrupt, self-interested and remote in the eyes of the population, and europeanisation continues to be something that will result in economic and social trauma for them, then those who offer a populist alternative will continue to flourish. While Moldovan politicians are starting to recognise this, it still requires a strong commitment to shift attitudes to power and politics away from a culture of immunity-seeking behaviour.

| 2010 | 2014 | |||

| Party | Votes | Seats | Votes | Seats |

| Communist Party of Moldova (PCRM) | 677,069 (39%) | 42 | 279,372 (17%) | 21 |

| Liberal- Democratic Party (PLDM) | 506,253 (29%) | 32 | 322,188 (20%) | 23 |

| Liberal Party (PL) | 171,336 (10%) | 12 | 154,507 (10%) | 13 |

| Democratic Party (PD) | 218,620 (13%) | 15 | 252,489 (16%) | 19 |

| Alliance ‘Our Moldova’(AMN) | 35,289 (2%) | 0 | n/a | 0 |

| Movement for European Action (MAE) | 21,049 (1%) | 0 | n/a | 0 |

| Socialist Party of Moldova(PSRM) | n/a | 0 | 327,910 (21%) | 25 |

| Reformed Communist Party(PCR) | n/a | 0 | 78,719 (5%) | 0 |

| Others | 91,452 (5%) | 0 | 183,357 (11%) | 0 |

| Invalid | 11,907 (0.6%) | 50,948 (3%) | ||

| Total(Turnout) | 1,720,993 (65%) | 101 | 1,649,508(56%) | 101 |

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

__________________________

Daniel Brett – Open University

Daniel Brett is an Associate Lecturer at the Open University, he has previously taught at Indiana University and the School of Slavonic and East European Studies. He works on contemporary Romania, rural politics and historical democratisation.

Ellie Knott – London School of Economics

Ellie Knott is a PhD candidate in the Department of Government at LSE researching Romanian kin-state policies in Moldova and Russian kin-state policies in Crimea. She tweets @ellie_knott