In recent years, Skopje underwent a process of city rebranding, reinventing itself along a past that, arguably, never was. The project was presented as a way of dignifying the city’s landscape and attracting tourists – but it mostly attracted international media’s scepticism and ridicule, and also exacerbated the long-running name dispute with Greece. The sums of money involved in the project have also raised questions of financial integrity.

In recent years, Skopje underwent a process of city rebranding, reinventing itself along a past that, arguably, never was. The project was presented as a way of dignifying the city’s landscape and attracting tourists – but it mostly attracted international media’s scepticism and ridicule, and also exacerbated the long-running name dispute with Greece. The sums of money involved in the project have also raised questions of financial integrity.

Critics point at a redrawing of the city boundaries: a process that risks perpetuating and entrenching underlining ethnic segregation. An often heard argument is that the dominant ethnicity, by claiming for itself a direct continuity with the historical region of Macedonia and reneging links to the Ottoman period, is pushing all non-ethnic Macedonians out of the city’s past – and therefore present. An alternative interpretation now emerges: the two largest ethnic groups might both have a stake in the project.

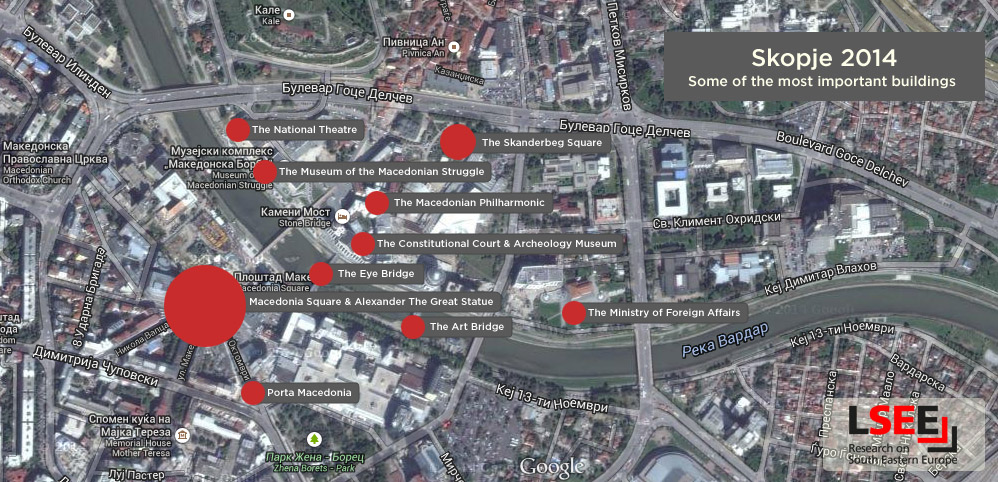

We are speaking about a very expensive four-year long endeavour: the estimates range from just above €200m (government estimate) to over €500m and even €1bn, from an initial figure of only €80m. The original plan was thus less ambitious than the execution turned out to be. As the megalomaniac statues and buildings casting a link to an idealised past were not opposed by mass protests and, on the contrary, the electorate seemed to fundamentally like them by reconfirming the ruling right-wing VMRO-DPMNE to power in the 2013 and 2014 elections, the government raised the stakes and went for an even bigger intervention in the city’s urban makeup. Several buildings are still under construction. ‘Skopje 2014’ (the name indicating the year of completion) might well, in fact, be running into 2015.

Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski prides himself of being the ‘architect’ of the project. The necessity for such pharaonic investment, according to the government line, stems from the need to give the city an improved look and to attract foreign visitors. Come the end of 2014, and the results are mixed at best: while the influx of tourists has risen over the past few years (though not to the level of Yugoslav times, and it is not clear to which extent kitschy statues contributed to this increase more than cheap Wizzair flights), the attempt to give the city more gravitas has hardly worked out so far. Most of the foreign commentary on the project focused on the controversial nature of the urban intervention, referring to it as a divisive makeover, a recreation of history, a theme park.

The 33m high Statue of Alexander the Great in Skopje. Photo Sinisa Jakov Marusic – Balkan Insight

Why then this project, if not (only) for touristic purposes? Those sceptical about the initiative have four main areas of concern: ethnic segregation, the name game with Greece, VMRO-DPMNE’s quest for votes, and economic gain.

Redrawing the ethnic boundaries of the city

The post-Yugoslav Macedonia is no homogenous state. The ethnical make-up of the country has been estimated in the last census to be 64.2% ethnic Macedonians, 25.2% ethnic Albanians, and between 1-5% each for Turks, Romani and Serbs. The country’s capital is similarly composite. Skopje 2014, it has been argued , is pushing a narrative that is serving well only the majority group, while marginalising the other minorities in town, who are losing their voice in the project. This argument overlooks a degree of complexity, as not all ethnic Macedonians feel represented by the project. On the other hand, another interesting phenomenon can be observed: sui generis claims to territory have also been advanced by radical members of the second largest ethnic group – the Albanian one.

While the great bulk of the intervention has focused on the ‘new’ centre of the city, i.e. the main square and the Vardar river waterfront, the Macedonian history rhetoric has not touched the ‘old’ Ottoman centre (čaršija). Truth be told, the čaršija has undergone major renovation and it is now a more secure and much livelier area, but it remains devoid of new statues and iconic buildings fostering the Alexander-the-Great connection. In spite of being truly multicultural, this part of town is arguably regarded as an Albanian stronghold, as is the Kale fortress towering on the top of the nearby hill. The best testament to it is the statue of Skanderbeg, Albanian national hero, located in the eponymous market square at the entrance of the čaršija and at the feet of the fortress. Numbers reinforce that: this area is part of the Municipality of Čair, where Albanians forms a convincing majority. We thus have a situation in which ethnic Macedonians are claiming the new city centre and leaving the old town to the sizeable Albanian minority.

The symbolic re-tracing of the city boundaries perpetuates divisions and instigates conflict. The most telling incident in this sense is the one that occurred on the Kale fortress in February 2011. Plans to build an Orthodox church (or was it a museum? authorities were ambivalent on this) infuriated members of the Albanian community, who felt their territory was being profaned. A clash between football supporters of the two ethnic groups followed. The episode led to high levels of hate speech, which arguably entrenched and radicalised voters from both sides.

The possibility of a more-or-less tacit accord between the two groups is not unthinkable, if analysed against the electoral dynamics: after all, the largest ethnic Albanian (DUI) and ethnic Macedonian (VMPRO-DPMNE) parties are together in a coalition government, and have been so for quite some time.

Statue of Skanderbeg, Albanian national hero, in Skopje

The name game with Greece

The 2008 NATO summit in Bucharest decided not to extend Skopje an invitation to join the Alliancebecause of its ongoing name dispute with Greece. Greece is refusing to accept the name ‘Macedonia’ as a valid denomination for the country and claiming to be the only rightful successor to Alexander the Great’s historical region of Macedon. At the time of the summit the confrontation between the two states reached new highs with little sign of any de-escalation in the years that have followed. This dispute is currently one the main inhibiting factors to Skopje’s accession to the EU and NATO. Though Greece’s objection to its neighbour’s EU and NATO bids has been ruled as illegal by the ICTJ in 2011, there has since been little real effort from both sides to reach a compromise, and Skopje 2014 is certainly not a step into the right direction.

For all the talk of sensible diplomacy from Macedonian officials, Skopje 2014 is a slap in the face for Greece. “We do not want to win the naming dispute against Greece”, Foreign Minister Nikola Poposki told LSEE in June this year, “we want to be real, economic partners”. But the towering 33-m high statuedepicting Alexander the Great – which the government claims to be ‘just any’ warrior on a horse – seems to contradict this statement. With this urban project, Skopje is raising the stakes of the diplomatic game.

Gaining votes

‘Antiquisation’, a much discussed concept in relation to Skopje 2014, can be summarised as the creation of a partially engineered past to serve a certain political rhetoric. In this way, the ruling VMRO-DPMNE is leveraging nationalistic sentiments and partially recreating the history of their own party, while reaffirming themselves as the true bearers of the Macedonian spirit. The newly built ‘Museum of the Macedonian Struggle for Sovereignty and Independence – Museum of VMRO – Museum of the Victims of the Communist Regime’ is a fine example: the name says it all. All aspects of the past (both Ottoman and Communist) that don’t fit into the VMRO-DPMNE narrative are erased.

The newly-built Museum of the Macedonian Struggle for Sovereignty and Independence – Museum of VMRO – Museum of the Victims of the Communist Regime // Photo Tena Prelec

VMRPO-DPMNE poster in Skopje, making heavy use of the national flag as a party symbol. The writing reads: “The people are our strength! The idea is our driving force!” // Photo Tena Prelec

Reconfirming VMRO-DPMNE to power in 2014, the Macedonian electorate has indirectly endorsed the project and confirmed that the antiquisation strategy is working. In spite of the clear authoritarian tendencies the ruling party has shown (remarkably, the ousting of opposition and journalists from the parliament in December 2012), the electorate’s support has not dwindled. A fundamental aspect of the ruling party’s success is their firm control on the national media landscape. Skopje 2014 will now serve as a permanent type of control over the Macedonian electorate: the statues will always be there to remind people what it means to be a ‘real’ Macedonian – and that only one political party can truly represent them as such.

Economic aspect

There is scope for an even more serious problem, linked to the great potential for economic gain originating from such big construction projects. The construction tenders were neither public nor transparent and the figures provided by the government in 2013 are hotly contested.

In 2013, when the opposition won in the municipality of Center, it started an independent audit of all the dealings of the municipality connected to the so called ‘Skopje 2014’. The audit report was only partially published and the full findings have been passed to the Public Prosecution. However, there is still lack of information whether the Prosecutor will continue the investigation. The independent audit still remains only partly published – and its full findings are to be watched closely.

These dealings are often referred to as money laundering, but this is a misconception: “if infringement is confirmed, it should be considered a theft and abuse of public office”, says Misha Popovikj, an anti-corruption researcher from Skopje.

Where does this leave us?

In the Greek-Macedonian name dispute, education and public perception have always been a major thorn in the side of meaningful negotiations. A balanced view of the issue among both populations is fundamental to moving negotiations forward. But both governments have over the years been complicit in stoking tensions for their own short term goals. And Skopje 2014 is not going to help break the deadlock; if anything, it will only antagonise Greece and make a settlement in the near future even less likely. To help break out of this impasse, the Macedonian government should stop raising the stakes in the name dispute with Greece. To regain economic credibility, the government should render all deals public and transparent as soon as possible; allow investigation into how they were conducted and the companies that took part in them. To foster ethnic integration, it should, finally, strive to make each Macedonian citizen feel represented in every part of their capital, regardless of their ethnic background, and embrace the beautiful diversity that for centuries has existed in their country.

The real problems – rampant unemployment, no real EU perspective, large-scale migration – cannot and must not be ignored. No panem et circenses strategy will be of much use to those who return to their hometown after years abroad and find it unrecognisable for the worse. In the words of one of them: “Skopje used to be about people, not about buildings. Now the people are gone, and the buildings are fake”.

_________________________

Note: This article was published in collaboration with The ProtoCity. It gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.