On Wednesday 8 October, outgoing Enlargement Commissioner Štefan Füle announced the Commission’s annual reports on the progress achieved by EU candidate and potential candidate countries. Our experts give an overview of the reports’ main takeaways for each country.

- James Ker-Lindsay: “Serbia: It’s time to start building a new EU state“

- Krenar Gashi: “Kosovo: Same alarms, no surprises”

- William Bartlett: “Bosnia and Herzegovina: Deep frustration at political stalemate”

- Kenneth Morrison: “Montenegro: The road to the EU may take longer than expected”

- Cvete Koneska: “Macedonia: The report’s criticism is unlikely to be taken seriously by the government”

- Joanna Hanson: “Albania: Moderate progress, but strong criticism of the parliament persists“

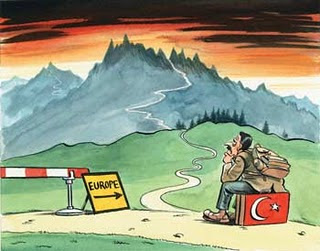

- Didem Buhari-Gulmez and Can Karahasan: “Turkey: Working on foundations“

Serbia: Time to start building a new EU state

Access the Serbia Progress report 2014

Dr James Ker- Lindsay, Senior Research Fellow, LSEE Research on South Eastern-Europe, LSE

Dr James Ker- Lindsay, Senior Research Fellow, LSEE Research on South Eastern-Europe, LSE

The past year has been especially important in terms of Serbia’s EU integration process. Since the last progress report was issued, the country has formally started accession talks. This was a major breakthrough and marked substantive proof of the progress the country has made over the past decade. However, this past year has also seen an election that led to the formation of a government that is widely regarded as being more authoritarian than its recent predecessors. In particular, there have been concerns expressed about its attempts to clamp down on press freedom. Moreover, the talks with Kosovo have all but come to a halt. With all this in mind, the latest progress report was awaited with considerable interest. So, how has the European Union judged Serbia’s progress since 2013?

On the question of Kosovo, the issue that has dominated Serbia’s relations with the EU in recent years, the report takes a fairly neutral line. As rightly noted, general elections in Serbia and Kosovo have been the primary factor holding back progress. As for the substance of the dialogue process, the picture actually tends towards the positive. It notes that Serbs in both the north and south of Kosovo participated in the June general elections and that there has been some progress in dismantling the contentious parallel structures. Meanwhile, Serbia has played a ‘constructive role’ in terms of Kosovo’s participation in regional initiatives and Belgrade has cooperated with EULEX, the EU’s rule of law mission in Kosovo. However, progress in other areas, such as the integrated management of border/boundary crossings (IBM), has been slow. Crucially, nothing particularly negative is flagged. As the report concludes, ‘new momentum’ needs to be found in the dialogue. All-in-all, the Commission seems broadly content with developments in this area in light of the political gridlock that exists. But obviously more is expected in the year ahead.

In terms of the domestic political situation, a rather more mixed picture emerges. Although the report suggests that Serbia’s institutions are broadly in line with European requirements, a lot of work needs to be done to bring them into line with European standards. Constitutional changes will need to be made and more needs to be done to strengthen those bodies that play a crucial oversight role. As the report noted, ‘the government still needs to develop its understanding of the role of independent regulatory bodies and to guarantee that these bodies have appropriate resources to perform their role effectively.’

A far bigger concern centres on justice and the rule of law. This is an area that has now been put front and centre of the enlargement process. Here the report presents a rather more negative picture. The Serbian Prime Minister, Aleksandar Vucic, has made the fight against corruption a centrepiece of his administration. And yet, while the report notes that there is a ‘strong political impetus to fight corruption’, it also notes that convictions, especially at a high level, are rare. Likewise, on organised crime, convictions are still far too few and far between. However, the big issue in this field is the judiciary. Judicial reform is a problem that has plagued many of the countries in the Balkans. Serbia is no exception. The report makes it very clear that rapid progress in this area will be seen as a litmus test for the country’s overall ability to proceed with accession. This is going to be something to watch.

In terms of the wider political environment, a strong message to come out of the report is the need to encourage the development of civil society. As well as taking more steps to incorporate civil society into the decision making processes, the report also raises concerns about the wider societal environment in which they operate. As noted, number of civil society groups face intimidation form the tabloid press and extremist groups. Allied to this, the section dealing with minority and human rights also raised serious issues. Although the report praises the decision to allow the Belgrade Pride March take place this year, the general lack of tolerance regarding LGBTI rights is worrying. This, in particular, has increasingly come to be seen as an indication of Serbia’s willingness to adhere to EU values of toleration. In general terms, the report therefore calls on the government to take a stronger role in promoting a culture of respect across society as a whole.

Lastly, the issue that has really stood out over the past year has been media freedom. Given this attention, the sections of the report dealing with this are rather short. While it notes the ‘deteriorating conditions for the full exercise of freedom of expression’ and highlights a lack of transparency over media ownership and a tendency to self-censorship, it stops short of directly pointing the finger of blame at the government (although it does speak cryptically of ‘undue influence on editorial policies’). Instead, the report emphasises that the government must play a role in creating the environment where the media can operate freely. Inevitably, this will fall far short of what many of the government’s most strident critics had hoped from the report. Nevertheless, media freedom will be under the spotlight from now on and Belgrade will certainly have to make sure the situation improves in the period ahead.

Overall, the picture that emerges is one of a Serbia that has done a lot in recent years to create the essential structures required to pass the initial hurdles of the EU integrations process. However, the country is now in a completely new phase. Things will get tougher from here onwards. Belgrade now needs to make sure that those structures function in a way that meets EU standards and that society as a whole starts to take on board the Union’s core values; not least of all, tolerance.

_________________________________

Kosovo: Same alarms, no surprises

Access the Kosovo progress report 2014

Krenar Gashi, PhD researcher, Centre for EU Studies, University of Ghent

Krenar Gashi, PhD researcher, Centre for EU Studies, University of Ghent

This year’s Progress Report for Kosovo was fascinatingly predictable. The country is praised for progress achieved in all three areas where the European Union had direct involvement or interest, while criticism persisted in key areas of governance.

In a nutshell, the report says the country made progress in the dialogue with Serbia, which is facilitated by the EU High Representative, in organizing free and fair elections, an achievement for which the dialogue is directly credited, and in extending the mandate of the EU rule of law mission (EULEX). It stagnated when it comes to independence of judiciary, politicisation of public administration and independent state institutions as well as the overall democratic spirit of governance, with the key result of the latter being the post-election stalemate. Economic stagnation, especially when put in a regional comparative perspective, is the most worrying one.

Although the indicators of success for the first three areas are evidently there and quite undeniable, one can still sense a dose of subjectivity of the Commission based on the way they were pointed out. The report gently acknowledges lack of concrete results from the dialogue with Serbia and its sustainability due to problems with the implementation of the reached agreements but does not take it into account for overall progress rated in this process for which Kosovo and Serbia are generally praised.

Similarly, Kosovo is praised for having organised better elections than the ones of 2010 that were characterised by industrial-scale fraud, and for having succeeding in organising elections throughout its territory. This by all means stands, but the lack of real choices for the Serb community in Kosovo as well as large-scale fraud which jeopardised real representation of smaller parties that had no support from the government of Serbia are somehow minimised.

The co-operation with EULEX is to some extent exaggerated as progress as it was a result of the EU’s persistence, and, probably, the lack of the overall success of the mission too. The only issue where Kosovo made substantial progress but where the EU is not ready to act yet – the Visa Liberalisation process – was quietly described with dull sentences lacking any kind of analysis or insights.

The latter is, of course, depending directly on the political willingness of the EU member states, and, when one reads the other areas where according to the Report Kosovo made little or no progress, it doesn’t come as a surprise. This is because the Kosovo government continued to interfere with the judiciary and failed to fight corruption and organised crime. The highly prioritised special anti-corruption task force filed only 5 cases during last year while interference with ongoing investigations persisted. Politicisation of the public administration persisted while accountability and service delivery made ‘very limited progress’.

The main stagnation, however, doesn’t require many words to describe. Four months after the June 8 elections, political parties continue to block the institutional life, having failed to establish the parliament and form the government. Although the Report is cautious not to take sides in this straightforward political petty-fight, it contains genuine criticism for both political groups. There is a good dose of criticism for Kosovo’s Constitutional Court too, due to its failure to ‘break the impasse’ with its two judgments on the matter.

The most important stagnation for Kosovo population is by all means the one in economic development. As the Report rightly notes, the pursuit of market-oriented policies ‘slowed down’ and ‘the predictability of economic policies weakened as a result of ad hoc approaches in policymaking’. Labour market policies were insufficient, public revenues declined, and the government’s pre-election decision to raise public wages has damaged the credibility of fiscal policy to say the least.

Overall, the Report reads that Kosovo made little progress towards the EU during the last year. As the incumbent government is likely to praise itself for such wording, it should be clear that ‘little progress’ in such a context means much, much worse than the country could do. The structure of the report leads one to conclude that the country continues to produce too much politics and too few policies.

_________________________________

Bosnia and Herzegovina: Deep frustration at political stalemate

Access the Bosnia and Herzegovina Progress report 2014

Will Bartlett, Senior Research Fellow, LSEE Research on South Eastern-Europe, LSE

Will Bartlett, Senior Research Fellow, LSEE Research on South Eastern-Europe, LSE

Almost every sentence of the general summary section of the progress report for Bosnia and Herzegovina expresses the deep frustration of Commission officials dealing with the country’s obstinate politicians. Progress with EU accession procedures, as well as political, economic and social policies, remains stalled by the inability or unwillingness of the two Entities to agree on strategies in key sectors and support the functioning of the State level institutions. Although the report tries to maintain a balanced approach to this difficulty (“the continued use of divisive rhetoric by some political representatives”) it is fairly clear that the main obstacle remains the stubbornness of politicians from Republika Srpska in their unwillingness to recognise the legitimacy of the State level institutions. The Report does mention the walkout of the delegates of the Republika Srpska from the House of Representatives that disrupted law-making capacity for several months earlier this year, as a result of which only four new laws have been adopted. Not surprisingly, the Report concludes that “there has been no tangible progress in establishing functional and sustainable institutions.” The political paralysis is well symbolised by the continuing closure of the National Museum in Sarajevo. General elections due on 12th October are unlikely to change this situation of administrative and political paralysis of the State.

The lack of agreement over state level functions and functioning has seriously disrupted the country’s EU accession process and prospects, and the EU assistance programme (IPA) has stalled. Despite the creation of a Joint EU-Bosnia and Herzegovina Working Group to accelerate the implementation of IPA projects, little progress has been made; €42 million of unspent funds has been reallocated to repair of flood damage. Bosnia and Herzegovina is now in danger of being left out from the IPA II programme that has just begun for the period 2014-2020. It is the only country in the Western Balkans that lacks a full IPA II Country Strategy Paper, which is the basis for EU assistance funding. Instead it is stuck with a limited Draft Paper, which covers only the years 2014-2017 and a limited number of sectors, entirely excluding key infrastructure sectors such as energy and transport and the important agriculture and rural development sector. Future EU assistance under the IPA II programme will require that a country develop a consistent set of sector strategies that can attract comprehensive funding. Countrywide sector strategies have been consistently blocked by politicians from Republika Srpska on the grounds that the central State lacks competencies in key areas of policy. This blockade threatens to deny EU assistance funds to Bosnia and Herzegovina in these key sectors. The Progess Report simply, but despairingly, concludes that “countrywide strategies for key sectors of economy need to be adopted”.

Some of the blame for this paralysis can also be laid on the Federation. In January, the Federation President suddenly dismissed the Federation Minister of Finance, which temporarily blocked repayments of international debts and negatively affected the implementation of the stand-by agreement with the IMF. Widespread civil street protests in February led to the resignation of several Cantonal governments. Political patronage networks are acknowledged to influence the operation of all level of government in both entities. The Progess Report concludes that “overall, no progress has been made by Bosnia and Herzegovina in improving the functionality and efficiency of all levels of government”.

In response to the policy vacuum, the Commission has announced three new initiatives. The first of these is a Structured Dialogue on Justice designed to deal with the much-needed reform of the judiciary, anti-corruption policies, anti-discrimination, prevention of conflict of interest and improving the performance of police forces. The second is in the joint working group on IPA already mentioned, and the third is assistance for strengthening economic governance through the creation of a Forum on Prosperity and Jobs, in direct response to the demands of the civil protests earlier in the year. The later is much needed in view of the alarmingly high level of unemployment that has reached 27%, with youth unemployment over 60%. Economic policy has remained restrictive under the conditions of the IMF standby arrangement, with a public sector deficit of just 2.2% of GDP backed up by continuing measures of fiscal consolidation such as a one-off cut in salaries in Republika Srpska. The poor performance of the economy is reflected in the continuing increase on the share of non-performing loans to a record 15%, despite some signs of economic recovery in the rate of GDP growth in 2013.

Yet all is not bleak. The report catalogues in meticulous detail the areas where, despite all, real progress has been made in a range of social issues. A law on a single reference number has been adopted, needed to ensure access to health and social benefits and travel documents for new-born children has been adopted in response to the “baby revolution” civil protests. Coordination between the state and entities over domestic violence has improved. Good progress is reported in meeting the housing needs of the Roma minority, as is an increase in primary enrolment of Roma children in some Cantons. The plight of the Roma remains however desperate with only two out of three Roma children attending primary school and less than a quarter attending secondary school.

Overall, the Progress Report on Bosnia and Herzegovina reveals a continuing crisis in the legitimacy of the State and a paralysis in policy making and the EU accession process that do not bode well for the future well-being of the citizens of this still politically divided country.

_________________________________

Montenegro: The road to the EU may take longer than expected

Access the Montenegro progress report 2014

![Kenneth-Morrison[1]](https://blogstest.lse.ac.uk/lsee/files/2014/10/Kenneth-Morrison1-e1412856153635.jpg) Kenneth Morrison, Reader in Modern Southeast European History and Co-Director of the Jean Monnet Centre for European Governance, De Monfort University, Leicester

Kenneth Morrison, Reader in Modern Southeast European History and Co-Director of the Jean Monnet Centre for European Governance, De Monfort University, Leicester

The latest European Commission (EC) progress report was the third since Montenegro opened accession negotiations in June 2012. Undoubtedly, the language is noticeably sharper in this latest report. However, the overarching tone of it is not as negative as many analysts in Montenegro had predicted, the government had feared or opposition parties had hoped for. In general terms, Montenegro has made respectable progress since embarking upon accession negations, but the opening of what were widely regarded to be the most problematic chapters for the government to address has determined that the early momentum has slowed somewhat. The latest report certainly suggests that Montenegro’s road to European Union (EU) membership may be a longer one than the government would like.

The report notes that sufficient progress has been made in terms of political criteria, forging a functioning market economy and developing the capacity to adapt, albeit slowly, to the challenges of European Union membership. They note slight improvements in the economic situation, while emphasising the need for reforms that will improve macroeconomic stability and labour market conditions. The report also acknowledges that the Montenegrin government has continued to ‘broadly implement’ its international obligations and that it has played a constructive regional role. The Montenegrin government are also credited with taking sufficient steps to strengthen the protection of members of the LGBTI population, noting in particular the October 2013 Pride Parade held in Podgorica which was ‘supported adequately by the authorities’. The report does highlight the demonstrative progress in these aforementioned areas.

The Commission does, however, raise a number of (ongoing) concerns, particularly with regard to chapters 23 and 24 of the acquis. These include the government’s insufficient efforts in combating corruption and organised crime, lack of action over accusations of ‘electoral wrongdoing’ during recent municipal elections, and slow progress in the area of judicial reform. The Commission also urged the government to take action to ensure that recent attacks upon journalists be investigated and that prosecution should follow ‘as a matter of urgency’. Additionally, the report stresses the need for the government to encourage and support media freedom and detract from making inflammatory or statements or statements that could be interpreted as intimidation.

Broadly, the report implies that if the Montenegrin government fails to act upon the recommendations of the report then the pace of negotiations may slow.

Overall, the report received a mixed response, with both the government and opposition parties highlighting only selective aspects of it while arguing over the broader implications. The government have, of course, sought to emphasise the positive aspects of the report, while the opposition have focused almost exclusively on the shortcomings identified by the Commission. Predictably, these binary interpretations were mirrored in the country’s print media. The pro-government daily Pobjeda trumpeted the government’s progress, while the pro-opposition dailies Vijesti and Dan endeavoured to present the findings of the report as evidence that the government is incapable of meeting the criteria required for EU membership. And in a highly-charged and divided political environment, such attempts to utilise specific aspects of the report to score political points will doubtless continue in the days and weeks ahead.

_________________________________

Macedonia: The report’s criticism is unlikely to be taken seriously by the government

Access the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia progress report 2014

Cvete Koneska, Central and Southeast Europe analyst for Control Risks Group, London

Cvete Koneska, Central and Southeast Europe analyst for Control Risks Group, London

This year’s progress report is a very good snapshot of the political situation in Macedonia. It highlights the key areas where more reforms are needed and where previous reforms have been rolled back. And the most important of them are in the Political Criteria section, signalling that EU’s greatest concerns are with the functioning of democratic political institutions and the rule of law in the country.

Although the EC recommends the start of accession negotiations, the tone of the report is predominantly critical. In particular, EC’s assessments of the situation with media freedom, judicial independence and the ‘colonisation’ of the state by the ruling parties illustrate that the quality of reforms and the overall democratic governance in the country has deteriorated over the past year. EC’s sharp language on these topics appears to have been intended to motivate domestic politicians to take action and accelerate reforms. The implicit threat is that the recommendation for starting accession negotiation could be withdrawn if the current trends continue for another year.

Nevertheless, it seems very unlikely that the Macedonian government will take the criticisms from this year’s progress report seriously and prioritise reforms of the judiciary, public administration or the media. The initial reaction of Prime Minister Nikola Gruevski, repeating his content of the renewal of the recommendation for starting negotiations despite the dispute with Greece, suggests that he is not overly concerned about the criticisms in the report. After five years of Greek vetoes to the start of accession negotiations, it seems increasingly obvious that EU’s progress reports are losing their transformation capacity in Macedonia. Regardless of what these reports contain and of what the government chooses to do about EC’s recommendations, Macedonia is not going to start accession negotiations, as Greece (and/or Bulgaria) is likely to veto this in the EU Council.

Although understandable, the government’s reaction to the EC progress report is concerning. A powerful lever for propelling domestic reforms appears to have been lost by the EU in Macedonia. A lever that is still relatively effective elsewhere in the region, as the progress achieved by other countries in the region, such as Serbia and Montenegro, demonstrates. Instead, in Macedonia the EU is losing influence and the government losing interest in continuing with the necessary democratic reforms.

_________________________________

Albania: Moderate progress, but strong criticism of the parliament persists

Access the Albania progress report 2014

Joanna Hanson, Visiting Senior Fellow, LSEE Research on South Eastern Europe, LSE

Joanna Hanson, Visiting Senior Fellow, LSEE Research on South Eastern Europe, LSE

Albania’s 2014 progress report was pre-dated by that country being given candidate status in June. This was a positive result to specific efforts made within the High Level Dialogue process. The report itself lists comparative progress and describes that progress as moderate. That notwithstanding, the document is a catalogue of strong criticisms of failures and recommendations seen previously.

Albania’s commitment to EU accession is acknowledged, in particular the consensual Resolution on European Integration adopted by parliament not long after the new Government came to power. The Commission still emphasises the need for increased efforts on Albania’s part.

The heaviest criticism is directed at parliament, the judiciary, public administration, rule of law and human rights. In parliament the opposition’s boycott prompted the need for constructive political dialogue to be stressed. Parliament is also criticised for its limited outreach to constituents. Independent institutions are criticised due to their appointment practices and their failure alongside civil society to be treated more seriously by parliament. There is still strong criticism of the lack of joined up-government.

The report acknowledges that significant Territorial and Administrative reforms have been adopted but wants considered and consistent efforts to be now put into their implementation. It mentions the continual problems of lack of transparency at local-government level. Likewise New Civil Service Laws and Public Administration legislation are commended but the report describes a hazy resulting situation where much still needs to be done. This was further complicated by the “reshuffling” of staff under the new government,. Judicial reforms are acknowledged but failures of that sector are described at length, in particular the politicization of the judiciary.

Human rights still receive a critical assessment despite correct praise for the Ombudsman. His work is seen as being disregarded and underfunded. The plight of the Roma is yet again highlighted. The protection of minorities is described as good in one part of the report and a mixed picture in another. Civil society is still seen as being fragmented and overly dependent on donor funding.

The text on the rule of law echoes previous reports. Although the fight against organised crime shows a positive trend in a number of areas, the report firmly states the Government lacks an overall strategic approach towards it on its territory. Trafficking remains a serious challenge.

The economic criteria are assessed reasonably positively but particular mention is made of the high levels of public debts and government arrears. The need to create more favourable conditions for investment was strongly emphasised.

In conclusion the Commission stressed the need for Albania to build on and consolidate the reform momentum and focus its efforts on tackling its EU-integration challenges sustainably and inclusively. Government and opposition were told to ensure political debate takes place primarily in parliament.

_________________________________

Turkey: Working on foundations

Access the Turkey progress report 2014

Didem Buhari-Gulmez and Can Karahasan, Visiting Fellows, LSEE Research on South Eastern Europe, LSE

Didem Buhari-Gulmez and Can Karahasan, Visiting Fellows, LSEE Research on South Eastern Europe, LSE

Didem Buhari-Gulmez on politics: substantial problems with human rights, rule of law, corruption and governance

2014 was declared as ‘the year of the European Union’ by Prime Minister Erdogan. At the time, this was seen as demonstrating Turkey’s persistent loyalty to the EU membership path, despite the increasing uncertainty around Turkey’s membership. However, the country’s policy towards Cyprus, in particular its refusal to expand the customs union to the Republic of Cyprus, which caused the partial suspension of accession negotiations in 2006 – continues to hinder negotiations and slows down the domestic reform process.

So far, accession negotiations have been opened on 14 chapters and of this number, just one (science and research) has been provisionally closed.

The European Commission’s 2014 progress report on Turkey raises concerns about various political issues. For instance, the report highlights shortcomings in the electoral process. Following the local elections of March 2014, and the Presidential elections in August, the Commission noted that the, ‘elections took place without adequate legal and institutional framework to audit campaign budgets, donations and candidates’ asset disclosures.’ In both votes, there were numerous allegations of fraud and discrimination.

In terms of governance, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government is criticized for passing laws that restrict the freedom of expression, including the internet law (which led to Youtube and Twitter bans that were reversed by the Constitutional Court) and the April 2014 amendments to the law on the National Intelligence Service that broadened the powers and scope of the National Intelligence Service.

#Breakingnews: #Erdogan confidant+twitter addict-Ankara Mayor M. Gocek sends smile to world #twitterisblockedinturkey pic.twitter.com/hwXkkzwNwU

— Louis Fishman (@Istanbultelaviv) March 21, 2014

The report emphasizes that in particular the media sector is under heavy political pressures putting the impartiality and independence of the media in jeopardy. Additionally, a lack of a healthy dialogue between the government and opposition parties in the Turkish Parliament, and the insufficient collaboration with civil society organizations, have served to reinforce the existing political polarization in the country, which in turn has delayed important reforms.

As with other acceding states, the rule of law and the proper function of judicial bodies are given considerable attention. Following the December 2013 corruption scandals that led to Cabinet reshuffle, the Commission has reminded Turkey that the fight with corruption is of key importance. In particular, it is thus crucial that Turkey changes the wide scope of parliamentary immunity in relation to corruption charges.

The government should also abstain from interfering into judiciary, and strengthen the autonomy and authority of the ombudsman. ‘The amendments to the Law on High Council of Judges and Prosecutors and the subsequent dismissal of staff and numerous reassignments of judges and prosecutors raised serious concerns over the independence and impartiality of the judiciary and the separation of powers.’

Another area of concern relates to civilian oversight of state security bodies. Referring to 2011 Uludere/Roboski case, where 34 civilians were killed in an air strike conducted by the Turkish army, and to the excessive usage of police force during social unrest, the EU notes that Turkey needs to improve civilian scrutiny of the military, the police, the gendarmerie and the intelligence services, and penalize the officers that violate human rights.

As regards the question of minority rights, the EU praises Turkey’s adoption of a preliminary legal framework to faciliate the social integration of former PKK militants and expand socio-cultural and linguistic rights of its Kurdish citizens. Yet, it also reminds that other minorities’ rights, such as the Alevi community’s right to Cemevi, should be taken more seriously.

In the context of foreign policy, Turkey is praised for its collaboration with the EU but Turkey’s sovereignty conflicts with Cyprus and Greece are emphasized as persisting significant obstacles against Turkey’s harmonization with the EU membership criteria based on good neighbourly relations. More positively, the EU report also commends Turkey’s efforts in terms of providing shelter to Syrian refugees and other refugees from the neighboring countries. It encourages Turkey to develop more effective mechanisms to deal with different problems faced by the (especially non-camp) refugees and internally displaced persons.

Unlike the last two progress reports, which were negatively received by the Turkish government, this year’s report has been generally found as ‘balanced’ and ‘objective, in the words of Volkan Bozkır, the new Minister of EU Affairs in Turkey. The country is likely to continue its reforms – albeit on a selective basis and its own pace — in spite of the persistence of the Cyprus conflict. Although Turkey’s adoption of the EU’s Cyprus conditionality is a precondition for full membership, it remains unlikely to guarantee Turkish accession to the EU given the substantial problems related to human rights, rule of law, corruption and democratic governance.

Can Karahasan on economics: Economic development is hampered by political tensions

The Progress Report on Turkey is structured over a number of pillars for economic policy: macroeconomic stability, interplay of market forces, market structure and business environment, legislative framework and financial sector development.

The report’s main takeaway in terms of economic policy is that political tensions are heavily influencing decisions in terms of economic policy, hindering the attainment of a consensus. The ongoing exposure of the Turkish economy to both domestic and international uncertainties has aggravated this tendency.

Other significant negative factors are the segmented structure of the institutions and the failure to reach full fiscal transparency. These two chief concerns outplay the positive aspects in the area of public debt sustainability.

In terms of monetary policy, the report recommends for the Central Bank (CBRT) to focus primarily on price stability, which has been a significant issue lately due to the domestic political tension, change in the international monetary conditions and instability in the region.

Other negative aspects comprised unfavourable conditions for businesses, slow progress in changing the legal framework underpinning economic reforms, problems in the education sector and the ongoing unemployment issue – which is heavily gendered.

However, the progress report also underlined a number of positive developments, including: the acceleration of privatization processes, the good functioning of the legal system for property rights, the strong financial sector dominated by banks and the continuing strive for EU integration.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of LSEE Research on South Eastern Europe, nor of the London School of Economics.

One comment on Kosovo. The Commission notes (p. 24) that “genuine sources of sustainable growth remain absent” there: this effectively means that today Kosovo has no future, and is kept afloat – we learn in the following pages – only by remittances, which partly show up as foreign investment, and foreign aid. This is hardly news, but rarely has this observation beet put in clearer and sharper terms: the reason, plainly, is the governance system: I suppose the whole report must be read under this light. “Progress” that takes the shape of new laws and policies is not, from this perspective, real progress; and yet that is most of the “progress” observed, with the notable exception of the decline in election fraud.