In the second part of her conversation with LSEE, Maria Spirova introduces the main players in the upcoming Bulgarian parliamentarian elections and elaborates on the phenomenon of electoral fraud. “Large-scale electoral fraud is expected by everyone – and this is exactly part of the problem”, she says. Read the first part of the interview with her here.

In the second part of her conversation with LSEE, Maria Spirova introduces the main players in the upcoming Bulgarian parliamentarian elections and elaborates on the phenomenon of electoral fraud. “Large-scale electoral fraud is expected by everyone – and this is exactly part of the problem”, she says. Read the first part of the interview with her here.

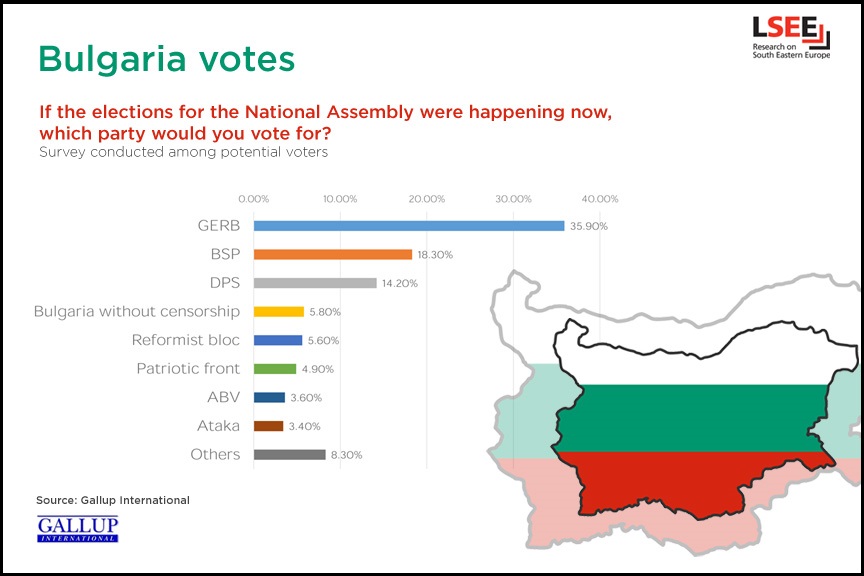

For an outline of all parties competing in the elections, check out Stuart Brown’s post on EUROPP.

In your previous conversation with us you have argued that Bulgarian parties are increasingly conveying the same messages. Could you take us through the political spectrum?

I wouldn’t necessarily call it a spectrum. It is more of a jumble of people who have a good CV in being in a party. Politics is not necessarily a calling in Bulgaria, it is a form of networking. There are a few very stable personalities and constellations around them that persist in Bulgarian politics.

DPS – Movement for Rights and Freedoms

There are a lot of facile things that could be said about this party. Chief among them would be that it is hated by a great number of the country’s Christian population because it is perceived to be the stronghold of Muslim Bulgarians, most of who are of Turkish origin.

However, the party performs an important function. It represents a significant minority within the country – around 10% of the population and as a consequence has been an ever present factor on the political scene since the end of Communism in Bulgaria. The DPS started simply as the champion of the Muslim and the Turkish-speaking minority, who were greatly marginalised during the later stage of Communism in Bulgaria. They were badly treated, especially in the late 1980s when the totalitarian government made attempts to make them more “Bulgarian” by insisting that they change their names to Slav versions, forbidding them from attending mosques and from wearing particular costumes and speaking Turkish. This greatly marginalised them and increased their desire for a party to represent their unique circumstances.

The DPS rode the need of these people for representation. As for its structure, most people that still make up the core of this party are former secret police agents – including its de facto leader, Ahmed Dogan. How is it possible that today’s leaders of this repressed minority once worked for the regime that carried out the oppression is one of the great mysteries of Bulgarian politics.

DPS is an extremely important party because it has held the balance of power in most parliaments since 1989. The party’s strength comes from the fact that it can always rely on the vote of the country’s Muslim minority no matter what. This minority often feels little affinity to the central state.

Parallels can be drawn to a certain extent with Egypt’s Muslim Brotherhood where Egyptians in underdeveloped and marginalised communities have absolutely no feelings towards Cairo and its official politics because the only access they have to social services is through the local organisations run by the Brotherhood. However, the DPS does not have the same faith-based approach to politics – it is a secular party with modern and highly organised structures. It is highly centralised with power based around a leader, Ahmed Dogan, who has been in pole position for 25 years. Although officially he is no longer at the helm of the party – recently replaced by Lyutvi Mestan, another former secret police agent from totalitarian times – Dogan remains the key decision maker in the DPS.

BSP – Bulgarian Socialist Party

The Bulgarian Socialist Party is the direct descendant of the Bulgarian Communist Party, which up until 1989 monopolised power in the country.

For the past 20 years the party has benefited from Bulgaria’s aging population and its nostalgia for the certainty that the communist years brought. We have about 6.5m people of voting age. Of them, around 40% never bother to vote. Usually, the voting percentages are weakest among young and educated people. They tend to be most disaffected by politics. On the other hand, Bulgaria has 2m pensioners. The lives of these people was spent in the sheltered safety of a society that made a great leap forward in the 1940s and 1950s before which Bulgaria was a largely agrarian society where tuberculosis was very common as was hunger. Communism led to the rapid industrialisation of the country which brought with it a significant jump in living standards, free medical care and largely put an end to hunger. Telling people that the regime which enabled all this was “not only wrong but also evil” is difficult for many people to stomach. These are the BSP’s core voters, who have only become more entrenched given the significant drop in living standards post 1989.

GERB – Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria

GERB is Boyko Borissov’s party, which styles itself as centrist, but it is certainly a party that is populist in any way it is possible to be so. Boyko Borissov started his career as the bodyguard to Todor Zhivkov, who was our communist leader and later as bodyguard to our exiled king (Simeon Saxe-Coburg). Before becoming Prime Minister in 2009, he was chief secretary to the ministry of the interior and mayor of Sofia. The image he projects is the one of a strong man who personally fights burglars with karate moves.

This party’s strength comes because it is made up of a great deal of ambitious people, with good connections in local municipalities and strong connections to big employers in local towns. What they lack in education is made up by raw ambition. GERB strongly supports Bulgaria’s membership of NATO and the EU, although both these milestones were achieved before they came to power.

Ataka

The appeal of far-right parties such as Ataka is based on outright and completely unmitigated ethnic hatred towards Bulgarian citizens of Turkish mother tongue. They are quite explicitly pro-Russian at this stage, because our alignment with Russia stems from it being our liberator from Turkish domination – from anything oriental, Muslim and – in our minds – backward.

To put the nationalist revival in a wider context, we recently had to handle a refugee crisis unseen in living memory in Bulgaria, which was for the most part a very isolated country. We have precious little idea of the diversity of foreign people who are not white western, and as such prestigious in our eyes, so in a sense there has always been a great tension in Bulgarian culture regarding how to deal with anyone who is even vaguely oriental – because we had to deal with this big trauma of being part of the Ottoman empire for 500 years.

Ataka, it turned out, lives and works very well with DPS – which should have been their mortal enemy – in terms of sharing power and arriving at agreements on all sorts of legislative issues, when necessary.

So clearly Bulgarian politics, especially at the nationalist end of the spectrum, are heavily engineered by the interests of key business players. Everything that could have been done to fragment the electorate and make sure that easily controllable people get into parliament and can be commandeered in different ways has been a mainstay of political play for about ten years now.

There have been strong allegations of electoral fraud in the past. Is there any way to determine if it will happen again or not?

In a society of the nature described so far, it would be more unnatural for electoral fraud not to happen. Large-scale electoral fraud is expected by everyone – and this is exactly part of the problem. On top of that, the efforts of certain initiatives to combat it or prosecute it fall on deaf ears, because we have a judiciary which is in no way interested in actually assisting the public and we have a public that is not very interested in assisting itself.

We have well established electoral fraud traditions that pre-date communism, which escaped it because there is no real point in defrauding a one-party election. Before the establishment of communism we thus had an election culture that didn’t work; then we had 45 years of no election culture whatsoever; and then we had what my family refers to “elections on an empty stomach”: it is today very easy to lure in hungry voters, and this sometimes happens literally by offering food at the polling stations.

Bulgaria has a very sizeable minority: the Roma. Nobody has ever been able to lucidly explain to the public how many Roma live in Bulgaria. We know there are many of them, and we know that we have been failing them hugely for the past 25 years. The Roma settlements are largely built in areas at risk and are therefore illegal, but nobody did absolutely anything to prevent it: in fact, Roma people were explicitly promised to that they will be able to keep living in the places where they built their houses if they vote in a certain way.

We must keep in mind that these are people for whom the state has never done anything, and they don’t care who runs it because they will still be discriminated against in the best case scenario. For them, this shoving off a paper in a little slip is a completely meaningless gesture, but is the most important negotiation tool at their disposal. If your entire livelihood depends on doing something which is completely meaningless to you, you do not hesitate.

There is a problem even wider than that: elections have never made Bulgarians feel empowered. There is a certain disillusion with elections everywhere, but I think that the idea that they are the sacred key to democracy is still widely accepted to be more or less true. That has never actually been the case in my country. What makes people vote is not the idea that they want a certain party in; it is the idea that they want a certain person from a certain party – that has irked them very much – out. It is thus very easy to manipulate elections where only the people who are sufficiently angry with somebody go and vote.

This removes a big part of the population who wants to vote “pro”: as said, politics is perceived as a criminal career, and nobody is taking people’s ideas seriously nor is listening to them. There is thus a self-selection practice that is very easy to manipulate. The other ‘unknowns’ in the elections are actually easy to predict: there is a corporate vote for the Muslim party which is rock solid; a pensioners’ vote which is sadly dwindling but still solid and easy to foretell; and a nationalist vote which will go to any nationalist scarecrow in vogue at the moment.

We therefore have very engrained social schemes that lead to electoral corruption.

Note: This article gives the views of the interviewee, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

____________________________

About the interviewee

Maria Spirova is a Bulgarian journalist based in the UK. She has held various editorial positions with the Bulgarian News Agency and other national media outlets in Bulgaria, and now publishes in Bulgarian and English, freelancing on socio-political topics for Euronews, The Economist, Kultura and others. She is the winner of the Reporting Europe Prize 2014, awarded for her series of articles on the Bulgarian anti-government protests which took place for most of 2013.