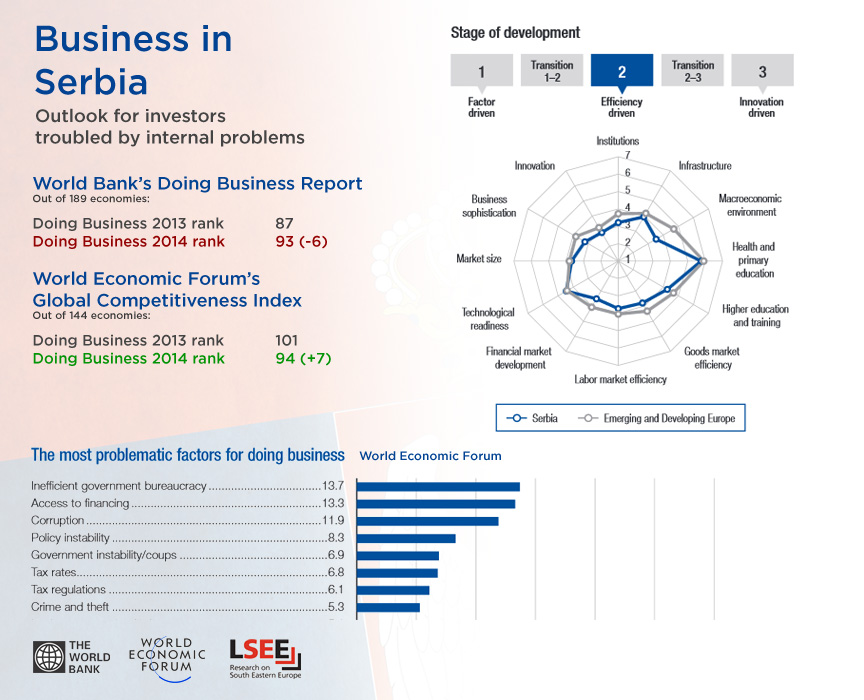

Unlike established market economies, in countries undergoing transition privatisation manifests itself as a large-scale property transfer and involves long-term consequences that can make or break their economies. Societal and political changes depend indirectly – though very closely – upon the way the process is carried out. Evidence has it that a big chunk of the most successful Serbian companies are still in state hands. This will have to change, if Serbia is to conform to the Western institutions’ trends of liberalisation and to cover up some of its budgetary holes. LSEE’s Tena Prelec discusses Serbia’s troubled relationship with the idea of privatisation.

Unlike established market economies, in countries undergoing transition privatisation manifests itself as a large-scale property transfer and involves long-term consequences that can make or break their economies. Societal and political changes depend indirectly – though very closely – upon the way the process is carried out. Evidence has it that a big chunk of the most successful Serbian companies are still in state hands. This will have to change, if Serbia is to conform to the Western institutions’ trends of liberalisation and to cover up some of its budgetary holes. LSEE’s Tena Prelec discusses Serbia’s troubled relationship with the idea of privatisation.

Serbia’s first wave of privatisation started in the early 1990s. The process came to be regarded by the wider public as deeply flawed. Successful privatisation was complicated by the Yugoslav “hybrid system of a managed market economy with somewhat fuzzy property rights”, but the most blatant problems were rooted in mischief: the uncertain international position of the country served as a cover for the misappropriation and transfer abroad of a great amount of funds by cronies of Milošević (see Palairet).

In these years, a large number of irregularities were observed, the most worrying of which being the connivance between tycoons and state bodies. The inability of the police and the judiciary to act effectively upon the wrongdoings completed the picture.

A second wave of privatisation occurred at the start of the 2000s. The situation improved, but not radically. Out of the main institutional flaws identified, the most serious were the lack of adequate controls on money laundering, unclear legislation concerning restitution, and a lack of adequate company valuation. The opacity of the origins of capital – and thus the opportunities for money laundering – was one of the main reasons why the privatisation process still had serious setbacks, and continued to be regarded by the public as deeply flawed.

In 2011, the European Commission pointed its finger at 24 dubious privatisations and demanded an inquiry into them. If Serbia was ever to be considered as a potential candidate country, it first had to sort out these controversial transactions.

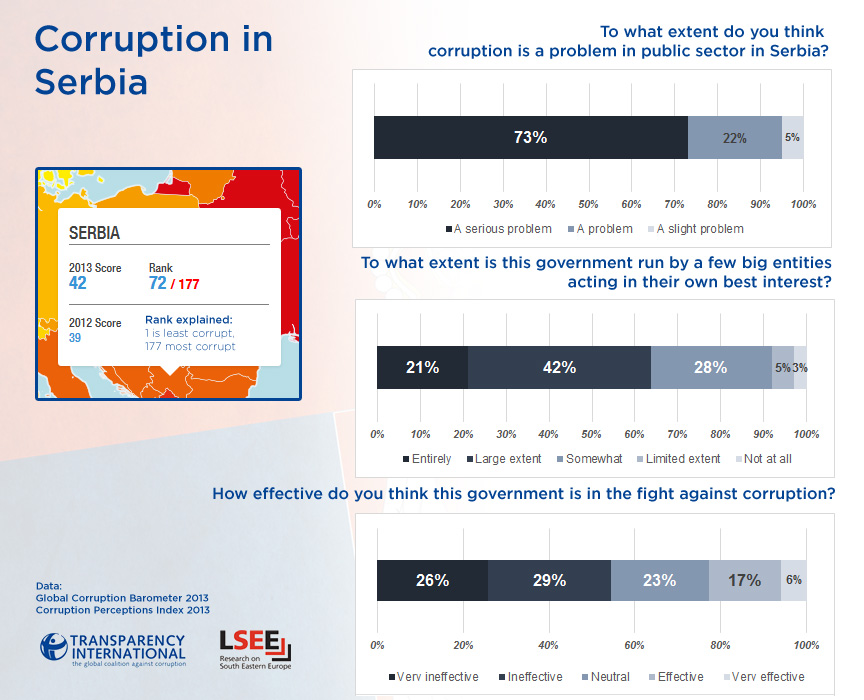

The request initially fell on deaf ears. A year later, Serbia’s rising political star – then Deputy PM Aleksandar Vučić – took up the challenge, put on his shining armour, and jailed the villains. Tabloids were convinced. Voters were, too – and landed him the premiership with 48% of the votes. International observers were, however, less enthusiastic: Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer 2013 did not record significant improvements.

A new wave of privatisation is now starting. Will the fight against corruption continue in a more effective way?

500 (smaller) companies up for grabs

In mid-August, the Serbian Agency for Privatisation announced a public invitation for the expression of interest for the privatisation of over 500, mostly loss-making, public companies. The deadline for the open call is 15 September 2014.

“While there is a consensus that many of these companies cannot be sold as going concern, this is a very positive step as there will be significant savings on public finances as a result of this process”, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s Director for Serbia Matteo Patrone tells LSEE.

It is high-time for the Serbian government to get rid of these companies, which are currently representing a big burden for the state coffers. “Overall, it is estimated that the burden on public finances is about €1bn, roughly 3% of GDP”, says Patrone.

Experts believe that not much can be expected from the privatisation of these companies. Because of their high indebtedness, there wasn’t much interest in them before. It is unlikely that today – in a rather stagnant local and European economic environment – things will be any different. “The main drive behind the acceleration of this process didn’t come from the need to speed up growth, but to lower state help and indirect subventions, and thus decrease the fiscal deficit”, says Mihail Arandarenko, economics professor at the University of Belgrade.

Indeed, responses did not seem to be overwhelming. Half-way into the course of the open call, we are informed that only about 40 expressions of interest have been put forward.

Not all of the listed companies are, however, negligible. The Mining and Smelting Complex Bor, one of the biggest businesses in Eastern Serbia, has assets estimated as worth €685m. Other companies which might attract interest are Grupa Zastava (carmaking) – €592m; PKB Korporacija (agriculture) – €294m; HIP Azotara (mineral fertilisers) – €267m.

But those are the exception, not the rule. A large number of the listed businesses are expected to be sold via liquidation proceedings: not equity deals, but asset deals. Investors likely to be interested in the purchase of companies will probably be actors, be it local or foreign, who already have an established presence in Serbia.

Update 19/09/14: The Serbian Finance minister Dušan Vujović has announced that the Agency for Privatisation received a large number of expressions of interest, primarily regarding the restructuring companies. Without specifying the exact number of letters, Vujović emphasized 60% of interested investors were “credible”. Blic Daily reported that the 126 expressions of interest received by 8 September concerned 87 companies, out of the 502 being offered for sale. If these data are correct, it would appear that a large number of these companies are still left without a purchaser.

The real deals are elsewhere – and have many question marks

If the public is invited to express interest for those mostly loss-making companies, it is still almost completely unclear which process will be destined to Serbia’s truly big businesses to be privatised.

When asked what can Serbia learn from the privatisations which took place in its neighbour countries, EBRD’s Patrone, whose institution defines privatisation as their “first priority” in the country, remarked: “Serbia itself has a mixed track record of privatisations and the authorities are paying a very high level of attention to lessons learnt from the past”.

Out of the companies ripe for privatisation, the EBRD has singled out three businesses to watch out for: Telekom Srbija, Dunav Osiguranje and Belgrade’s Airport Nikola Tesla.

Telekom Srbija’s privatisation (the second one) was initially planned for May 2013. It offered an attractive opportunity to raise money quickly. Assets of Telekom have been estimated to €1,5bn – to be compared to overall €5bn state deficit. However, the deal was postponed because of persisting uncertainty in the leadership of the Ministry of Economy. “I am afraid that the value of the asset will not benefit from any delays to the process”, says EBRD’s Patrone. “There was an indication that the process would have taken place in 2014 to compensate for budget deficit, but this has been covered from other sources, like the $1bn loan granted by the United Arab Emirates”.

In the longer term, however, there is some market chatter that Deutsche Telekom would be potentially interested in the company, strengthening its presence in a region where it already has significant share in leading telecoms in Austria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Experiences of recent years show that the best way to privatise Telekom Srbija may be via the so-called dual track approach, with potential listing in Belgrade and London, or an outright sale. Experts involved in Croatian Telecom’s earlier privatisation suggest that Serbia might take lessons from that experience. The Croatian company’s privatisation commenced in 1999 and has in recent years been heavily impacted by the broader negative economic trends in the country’s economy and by Croatia’s accession to the EU, which has further exacerbated the downward pressure on revenue and profit owing to imposition of EU regulation related to roaming charges. The introduction of an foreign shareholder for Telekom Srbija is encouraged, as it would help establish corporate governance standards, give comfort to international investors in future and help restructure the company even before the EU accession – which is unlikely to happen before 2020.

The insurer Dunav Osiguranje needs a deep turnaround before being put on the market, according to Patrone. Nonetheless, recent allegations have pointed to the interest of the German colossus Allianz in taking a majority shareholding in the company.

The key question for Belgrade Airport’s privatisation (which will probably take the form of granting a concession) is one of how much money will actually go into the state coffers. As a result of last year’s deal with UAE airline Etihad, the activity of the newly-founded Air Serbia has brought in more traffic than expected. It will therefore most likely be necessary to build a new terminal, and a large amount of money stemming from the private involvement might be required to meet these costs. The process, if correctly conducted, may bring limited relief for the budget in the short-term, but raises hopes that the airport will develop further.

The very Etihad-Air Serbia deal is one which has not escaped controversy. A recent investigation by BIRN, which got its hands on a draft contract before the official agreement was released, showed that the Serbian government paid a considerably higher price for its 51% stake in the business than the UAE partners did for their 49%. While the sole fact that a state pays a very high price to try to save an ailing airline might not in itself be extraordinary (Alitalia being one of the comparable cases), the secrecy behind which the arrangement has been shrouded is worrying.

Another deal set to attract media attention is the privatisation of the football club Crvena Zvezda, in which the Russian energy giant Gazprom has expressed an interest. There are rumours that Vladimir Putin will sign off the deal during his visit to Serbia in October.

In short – there is as yet no reassurance that the process for these or other large companies will be transparent, free and fair.

Aleksandar Vučić’s much-touted fight against corruption in 2012-13 (which consisted largely of punishing those accused of wrongdoings during earlier privatisations) was an important contributor to his winning a landslide victory in March 2014. It is to be hoped that he will now make every effort to ensure that the privatisation process he is overseeing runs smoothly.

One of the crucial aspects concerns the bidding procedure. Will off-shore companies registered in places such as the BVI, Bahamas, whose real owners are very difficult to check, be allowed to bid? The experts we spoke to do not think they should be. What does the Serbian government think?

Data editing by Jakub Krupa

Note: This article gives the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.