The South Stream gas pipeline is counter-effective when it comes to diversification of gas sources and, on top of that, it is absurdly expensive. But the economics do not matter here: Russia will pursue the project purely out of political reasons, writes Wojciech Jakóbik.

The South Stream gas pipeline is counter-effective when it comes to diversification of gas sources and, on top of that, it is absurdly expensive. But the economics do not matter here: Russia will pursue the project purely out of political reasons, writes Wojciech Jakóbik.

Europe has already been importing gas from sources other than Russia, like Algeria or Norway. The recently reinforced goal of further diversification in the light of the Ukraine crisis forces the Union to seek new sources. The Caspian and Mediterranean regions seem to be the most attractive basins to draw from.

But to achieve this, EU member states would need to agree on further infrastructure development, both within and outside the European Union. The aim is to connect the markets, improve gas flow between the member states and to foster diversification in Central and Eastern Europe, which is much more dependent on Russian hydrocarbons than other parts of the continent.

Making the market more fluid through the use of new volumes from different suppliers is another road to be taken into account. All of this is done under the umbrella of the EU anti-monopoly laws preventing one supplier to take advantage of its customers. And that is the logic which seemed to lead European work on deepening the diversification. The European Commission wants to subdue new Russian projects and adjust them to this logic using the anti-monopoly law of the Third Energy Package (TEP).

The numbers – a change in quantity, not quality

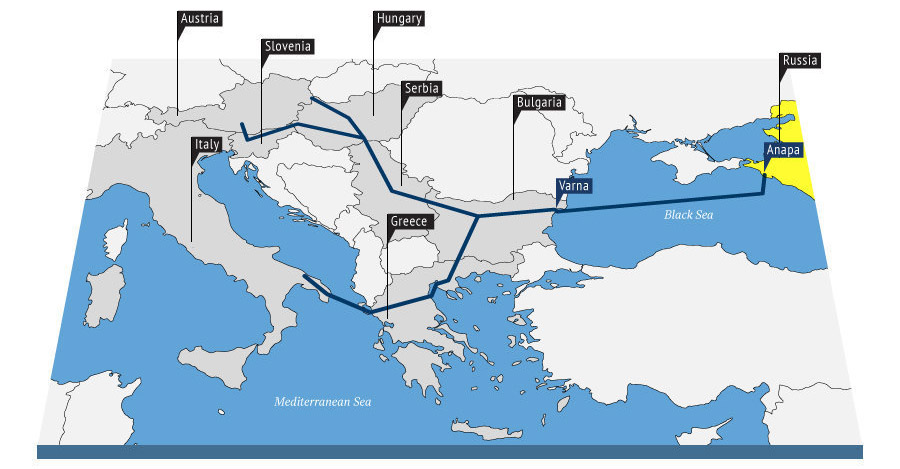

South Stream is simply about giving Europe even greater volume of Russian gas. It is supposed to achieve the capacity of 63 bcm a year in 2016 and will bring the volumes from Russian gas transit system, through the Black Sea, to Bulgaria, Hungary and Austria. The project includes branching in transit countries of South Eastern Europe such as Serbia. These countries have been already getting Russian gas via existing infrastructure. So for the region South Stream is a change in quantity, not quality.

The overall Russian export of gas to Europe in 2013 (without Ukraine) was 161,5 bcm. The main routes are Nord Stream (Baltic Sea) with a capacity of 55 bcm per year, Yamal-Europe (Belarus) – 33 bcm per year, Soyuz (Ukraine) – 80 bcm per year and Blue Stream (Turkey) – 16 bcm per year, for an altogether capacity of 199 bcm a year. It is important to underline that these pipes are not being used to their full capacity so far – for example, Nord Stream is being used at only 50 per cent of its capacity. Even according to Russian estimations Europe will need no more than 145 bcm in 2025 and 185 bcm in 2035. If so, why would Gazprom need such overcapacity?

Just another tool of energy politics

South Stream is nothing more than just another tool of energy politics. Using the capacity of both South Stream and Nord Stream, Russia will be able to resign from transit via Ukraine and Belarus if it wishes to do so. The risk connected with transit through those countries will disappear – and so will the political leverage of transit countries.

European TEP rules do not allow one supplier to maintain full control over the pipelines, but Moscow is fighting for OPAL, a German extension of Nord Stream, and South Stream to be exempted from this regulation. Having absolute control over these pipelines, Moscow will be able to cut supplies to Ukraine and transit countries without any negative consequences for EU customers. This will result in an increasing political will of Moscow to influence its former republics in a way that would threat their sovereignty. Gas wars similar to those between 2006 and 2009 could be fought with no impact on the European Union.

This tool is so important to Russia that the Kremlin is ready to pay any price for it. Costs of the Russian energy investments are going higher and higher. According to Ukrainian estimations, the South Stream project requires a modernization of Russian pipelines worth about $17bn and the total cost of the investment is likely to reach $73 bln. To put that in perspective Nord Stream costs reached ‘only’ $10 bn (while the forthcoming Russia-China gas pipeline called The Power of Siberia is going to cost $55bn). The only answer to the question of why would Russia spend such a large amount of money on yet another pipeline in Europe is clear: politics.

Diversification efforts: the Trans Adriatic Pipeline

Looking from the perspective of the European logic of diversification South Stream is useless, unless its compliance with the EU anti-monopoly law is proved. This logic is at the basis of the European Commission’s efforts to bring the idea of Trans Adriatic Pipeline (TAP) into life: connecting Italy with the TAP would supply Europe with gas from Azerbaijan and perhaps from other Caspian states. The TAP’s capacity is only 10 bcm a year so it is just a beginning of opening the Southern Gas Corridor to which South Stream volumes could add significantly, but if Russians would accept European understanding of diversification.

But they will not do so. They want to keep their strong position in Eastern and Southern Europe. They want to achieve bigger advantage over transit countries like Ukraine. The Kremlin’s objective is also to keep using energy to shape foreign policy. The real question therefore is as follows: should Europe let them proceed with the plan?

There seem to be no clear answer to this question, despite the debate going on for years.

An attractive deal for the Balkan countries

The Member States engaged in South Stream project are Bulgaria, Serbia, Hungary and Austria, supported by France, Germany and Italy, all three of which participate in the South Stream consortium along with Gazprom using their state-owned companies: EDF, Wintershall and Eni respectively. There is also a possibility of Greek, Montenegrin and Italian branches being created in upcoming years.

As all investment costs are on Russia, the deal is attractive, especially to poorer Balkan countries. In exchange for their consent to the South Stream project, the countries will get cheaper gas and profits from transit tariffs. In fact, the EU tried a similar model with Nabucco pipeline, supposed to transport gas from Azerbaijan and other Caspian countries to European markets, but has fallen short of necessary political support for completion. A successful example of similar investment is the Trans Adriatic Pipeline itself, however the very limited geopolitical impact makes it quite incomparable to South Stream.

Energy solidarity is abstract, but needed

The greatest takeaway from the early development stages of the South Stream pipeline is that many European countries value economic deals with Russia more than the abstract idea of energy solidarity.

This is how Russia divides Europe by using energy. And this is how things will work if we forget about the logic of diversification as the underpinning principle behind the European Union’s gas policy. If we do, the numerous European friends of Russia and Gazprom will fight to keep business as usual in relations with the Russian energy sector. And Russia’s divide et impera strategy will prevail.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

___________________________

Wojciech Jakóbik is Energy Sector Analyst at the Jagiellonian Institute in Warsaw, Poland. He is also Editor-in-Chief of BiznesAlert.pl economic portal. He is on Twitter @wjakobik.

Mr . Jakobik ,

There are two aspects in Russian gas export :

1. How to limit Russian influence / leverage on transit countries .

Your article covers that in debt. However , for the countries involved

much more important question is their profit.

2 . Why European anti monopoly laws are a concern for the Southern pipeline

but not for Ukraine ?

It looks that we are more interested to prevent Russian leverage than with

the well being of the EU in general and the Eastern Europe in particular.

What alternative you offer to these countries ?

Who will reimburse THEIR loses ?

It is, in fact, dubious whether the South Stream is an “attractive deal” (in the author’s words) for poorer Balkan countries. The latter assume loans from Gazprom to finance their participation in the project – loans that they may (or may not) be able to repay via the pipeline’s operation. Further, these are no formal agreements between Gazprom and Balkan countries on either anticipated gas price reductions or transit fees (thus, profits). Provided there is absolutely no clarity as to the economic and financial parameters of this project, the only attractive aspect of the South Stream remain abundant opportunities for the political elite to siphon financial resources from the project, as well as socially visible (and popular) project effects like temporary employment during the construction phase.