Education systems in the Balkans are highly selective: best performing students gain entry into gymnasia, while others attend vocational education training (VET) schools. Children of VET-educated parents are likely to follow in their genitors’ footsteps. High rates of vocational enrolment, furthermore, are not matched by effectiveness in skill formation. A large research project by LSE researchers, whose overview has been recently published by the European Training Foundation, suggests that allocating more resources, improving teacher training and updating curricula are key measures to allow for a change of tide. Will Bartlett and Claire Gordon summarise the findings.

Education systems in the Balkans are highly selective: best performing students gain entry into gymnasia, while others attend vocational education training (VET) schools. Children of VET-educated parents are likely to follow in their genitors’ footsteps. High rates of vocational enrolment, furthermore, are not matched by effectiveness in skill formation. A large research project by LSE researchers, whose overview has been recently published by the European Training Foundation, suggests that allocating more resources, improving teacher training and updating curricula are key measures to allow for a change of tide. Will Bartlett and Claire Gordon summarise the findings.

An improvement in vocational education and training (VET) in the Western Balkans is urgently needed to boost the skills of the labour force and ensure that the benefits of recovery from the deep economic crisis of recent years are widely spread among the population. Due to the heavy impact of the economic crisis in this region, unemployment has reached extreme levels. For example, in Bosnia and Herzegovina the unemployment rate is 27.5% according to the Labour Force Survey for 2013, while the youth unemployment rate is 59.1%. The risk of further social unrest, as seen in Bosnia earlier this year, will remain unless young people are provided with the skills necessary to access productive jobs and secure a more optimistic future.

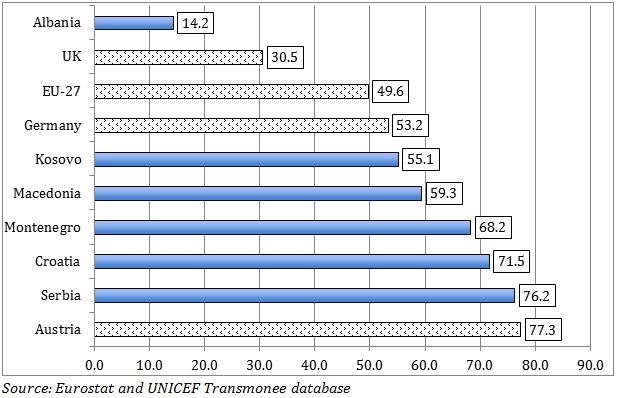

Education systems in most Western Balkan countries are highly selective. Better performing students gain entry into gymnasia (similar to the old British grammar schools) while others have the option to attend vocational schools. Although attendance at secondary education is not compulsory (Macedonia is an exception in having made attendance at secondary level compulsory in 2008), most students attend secondary schools. Enrolment in VET schools varies, being relatively low in Albania in comparison with the EU average, and higher in the countries of former Yugoslavia, where the share of secondary students in VET schools approaches the Austrian level (see Figure 1), often considered a best example of vocational education. However, the high rates of vocational enrolment do not reflect similar levels of effectiveness in skill formation as has been achieved in Austria.

Figure 1: The share of students at ISCED level 3 in vocational programmes

A recent participatory action research project carried out by researchers at LSE and local research partners has investigated the dimensions of social exclusion in secondary level vocational schools in the Western Balkans, where the system of education is highly selective. The research also investigated vocational schooling in Turkey and Israel, countries which face similar needs to improve social inclusion in their VET systems. In all, 84 in-depth interviews were conducted with key policy makers and other stakeholders and 223 interviews were held in schools and local communities. These, together with 745 teacher questionnaires and 2,862 student questionnaires, form the evidence base of this research. The study generated nine country papers and an overview paper written by researchers from the LSE that has been published by the European Training Foundation.

The research underlined the role of VET schools as an important source of transmission of social exclusion, pinpointing a series of ‘sites of social exclusion’ that were identified as critical points in the education cycle at which the risk of social exclusion may be accentuated or lessened (entry into school, the schooling experience, and transition from school into work or further education). The prevailing situation highlights the cascading effects of social exclusion as students progress through their VET school career.

Entry into school

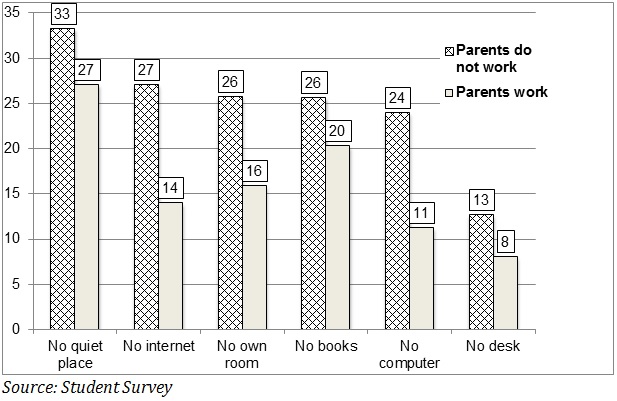

The selective entry process limits upward mobility of students since most students who attend VET schools follow in the footsteps of their parents, who also tend to have been to VET school. Working class young people and students from disadvantaged backgrounds are more likely to be channelled into VET school compared with children of middle class parents who are more likely to enter academic schools. Students whose parents are economically disadvantaged are also less likely to receive support at home for their studies (see Figure 2), normally an important element of the learning process in the Western Balkans where students are expected to receive substantial support from their parents.

Figure 2: Parental work status and lack of home study support

Experience at school

Once students enter VET school they frequently experience a poor educational environment, which holds back their learning and subsequent integration into the world of work. While almost all students recognise that success in school is very important for their future job prospects, the school experience in many cases appears to reinforce the social exclusion of disadvantaged students. The researchers found evidence of poor infrastructure at VET schools due to underinvestment in equipment and buildings, obstacles to effective learning due to out-dated curricula that have not adapted to changing labour market needs, poor teaching methods and weaknesses in teachers’ subject knowledge.

Curriculum development in Bosnia and Herzegovina. The curricula for certain subjects have not been changed since 2003 (IT) and for some even since 1994. The school is allowed to change only 10% of its curriculum independently, while the responsible ministry establishes the rest through extensive bureaucracy. In the case of vocational schools specialised in technology, like Sarajevo or Mostar, an ever-changing subject, there is a need to adapt the curriculum to modern developments on a regular basis. Despite the pressing need to update the curricula, teachers are often not in favour of changing the teaching program because they fear that they might lose their job as their field becomes out-dated. (Branković and Oruc)

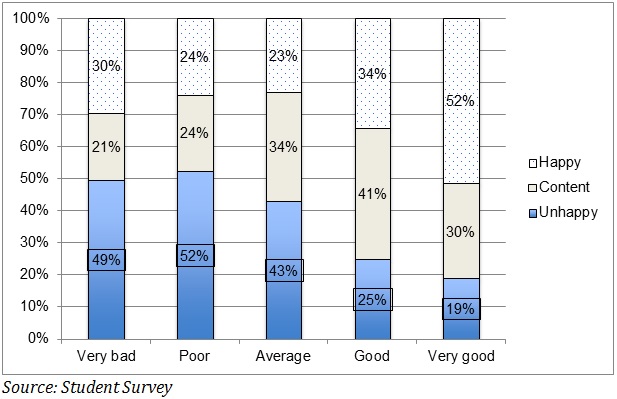

Although most students are happy at school, there is a minority of students who has had a disappointing experience. These students are more likely to have been bullied by other students, find teachers unfriendly and have a poor learning experience (see Figure 3). Disabled students and those from disadvantaged backgrounds typically fall into the category of students who have an unsatisfactory experience at school.

Figure 3: Teachers’ subject knowledge and student happiness at school

With regard to practical training, the hours spent in work placements in a company differ widely across schools and countries, and preferential access to apprenticeships given to more advantaged students. On the whole, there is insufficient practical training to provide many students with a sound basis of vocational knowledge and experience. There are nevertheless examples of good practice, such as in Foča (Bosnia and Herzegovina) where teachers visit and develop close relationships with the businesses where students receive practical training. As a result, one employer from Foča noted that students often stay longer hours than necessary in order to learn more on their own initiative.

Transition to work or higher education

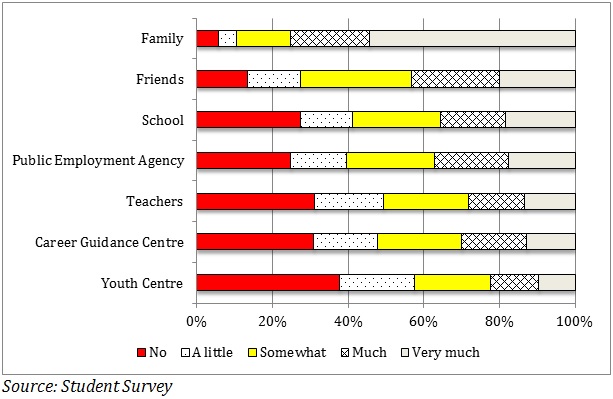

On leaving school, students receive little formal assistance in finding a job, and tend to rely far more on assistance from family and friends than from public employment services or career guidance institutions (see Figure 4). This highlights the importance of social capital and networks of connections in supporting the transition from school to work in the Western Balkans. Students with a high level of social capital are more likely to find a job and make use of the skills that they have learnt at school.

Figure 4: Expectations of sources of help in finding a job

Modernisation of VET systems has been taking place at differing speeds in the countries covered by the research project, with national priorities being set in line with EU goals and objectives for VET as outlined in the EU Strategy ‘Education and Training 2020’ and the Bruges Communiqué of 2010. VET policy orientations in WBTI countries vary between those that emphasise social inclusion and those that focus on adjustment to the labour market, but in both cases slow progress has been made in establishing horizontal institutional structures including VET Councils and occupational Sector Councils that facilitate a more participatory approach to the setting of VET policy.

Policy makers in the region are aware of the difficulties facing VET education, and participated enthusiastically in the research project. The research findings have been presented at policy workshops in each of the countries involved in the study to gather comments and feedback from practitioners and policy makers. These comments were reflected in the final report, which makes several recommendations for policy change including provision of more resources to vocational schools, improved teacher training in the dimension of social inclusion, updating the curricula with the participation of local employers, and focusing on improving teaching methods and teacher-student relations. Schools are also encouraged to forge stronger links with their local communities and involve local voluntary non-profit organisations in the provision of extra-curricular activities. Several examples of new policy initiatives in the region can be attributed directly to the research project and its findings.

Researchers of the LSEE Research Network on Social Cohesion in South Eastern Europe who have contributed to this project: Will Bartlett, Nina Branković, Jadranka Kaludjerović, Nikica Mojsoska Blazevski, Nermin Oruc, Marina Cino-Pagliarello, Claire Gordon, Simona Milio, Nermin Oruc and Merita Xhumari. Analysis of the research results is continuing; papers investigating different aspects of the study were presented at a workshop of the LSEE Research Network’s Working Group on Education in Skopje in May 2014. The Workshop was supported by LSEE and the World Bank Office in Skopje, and organised by Nikica Mojsoska Blazevski of the American University College Skopje.

___________________________________

Dr Will Bartlett is Senior Research Fellow in the Political Economy of South East Europe at LSE Research on SEE, London School of Economics. In 2006-08 he was President of the European Association for Comparative Economics. He coordinates the LSEE Research Network on Social Cohesion in South Eastern Europe.

Dr Claire Gordon is Teaching Fellow in East European politics at the European Institute, London School of Economics. Her research interests include EU enlargement and conditionality, the EU’s relation with the rest of Europe, conflict management and minority protection, and the challenge of Roma inclusion and social cohesion in the Western Balkans.