“Voting is by number, and it will always harm the interests of a minority. A protest is disruptive and reflects intensity – it really shows how much you care about something.” – argues Dr Sherrill Stroschein, Senior lecturer in Politics at University College London.

“Voting is by number, and it will always harm the interests of a minority. A protest is disruptive and reflects intensity – it really shows how much you care about something.” – argues Dr Sherrill Stroschein, Senior lecturer in Politics at University College London.

In 1990, the Hungarian minority in Târgu Mureș, Romania, engaged in a protest over language policies. The outcomes were surprising: a locally-brokered solution brought to the reciprocal election of new officials. Last October, Stroschein gave a presentation at LSEE on this topic. Here is our interview with her.

Sherrill, you told LSEE’s audience that “even after violence, there can be reconciliation and belief in common institutions”. How did this play out in the conflict between the Romanian majority and the Hungarian minority in Târgu Mureș?

There are two aspects to this. The first is about the violence itself. There was a riot in March 1990 in Târgu Mureș, in Romania, between Hungarians and Romanians. What was fascinating was that there was a local resolution to the conflict. The EU wasn’t there, the central government didn’t really work, the army showed up quite late, and the process in coming out of that violence was a locally brokered one, which involved local meetings and the resignation by the officials that had been involved – or who were perceived as being involved. Interestingly, new officials were chosen through reciprocal voting: Hungarians chose Romanians and Romanians chose Hungarians. This was decided locally, on the spot. It happened at the crucial moment, few days after the violence.

Secondly, there is a long-term answer to this question, which has to do with the way in which minority protests become a means for minorities to express what they are willing and what they are not willing to accept (in this case, in terms of language policy). This is important because voting itself doesn’t reflect the intensity of their claims: voting is by number, and it will always harm the interests of a minority. A protest is disruptive and reflects intensity — it really shows how much you care about something. In the case of the Târgu-Mures protest, a process of de facto deliberation took place, whereby the Romanians began to see that the Hungarians had some issues they werenot going to give up on, such as language. As the Romanians are the majority, it would be easy for them to simply outvote the Hungarians. But because Hungarians were protesting in the streets, they could not just be ignored.

An important theme of your research concerns the way masses and elites engage in mobilisation. What are your main findings on this regard?

There is a dominant line in conflict literature according to which elites manipulate masses. That is, however, not what has happened in the case of the Târgu-Mures riots and in other kinds of mobilisations in Romania as well as in Slovakia. The pattern that can be observed is that generally idealistic members of the minority, frequently students, are mobilised first, over an issue about which they are genuinely concerned. Usually what happens next is that elites join in, realising that there is an opportunity for a large mobilisation that they want to put their stamp on. This is exactly what happened in Târgu-Mures: Hungarian elites joined in after these more idealistic individuals started the protest. And then, if it becomes a very large minority mobilisation, you can have a counter-mobilisation by a majority – meaning that non-elite Romanians may respond if there are manyHungarians on the streets. Hopefully these counter-mobilizations will occur at a different place and time, as simultaneous mobilizations increase the probability of clashes between groups. The majority elites, here the Romanian elites, tend to be less connected to what’s happening with their population. It is kind of a luxury the majority has: they worry less about mobilizations, as in a regular democratic political system, majoritarianism takes care of their needs.

Is this looser connection between elites and masses in the majoritarian group (here: Romanians) a pattern which you would apply to other instances as well?

I think so, even though it would have to be further researched. But I would indeed hold these cases as a basis for comparison: the idea is that someone could take these insights and look into other scenarios to check if the same mechanisms are present there as well.

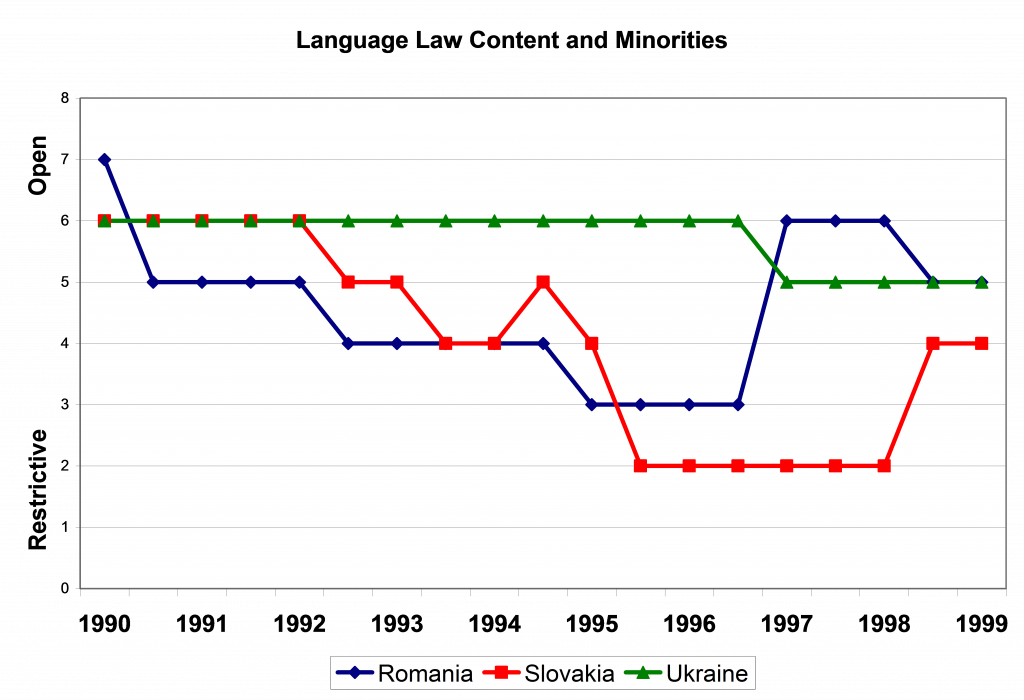

Your insightful graph about the content of language laws in Romania, Slovakia and Ukraine demonstrated that EU enlargement did not so far go hand-in-hand with the openness of laws for language minorities. What is going wrong?

I think that, at the end of the day, most politics is local. The EU makes a lot of claims about fostering democracy, tolerance and pluralism, but it is in fact a quite detached entity. There is a lot of patronising literature on this matter (about the EU “civilizing” the East), however at the end of the day people will act on issues close to them. I do not see the EU ever changing that.

Do you reckon ‘shared belief in common institutions’ to be a possible, eventual, outcome in the case of Kosovo as well?

There is a much more complex situation in Kosovo: there we are talking about long-term violence. But in the case of Târgu-Mures the crisis had a short-term nature. There might be some similar mechanisms of conciliation that could emerge, but they would take longer given the intensity of the violence. In most conflicts, however, there is a tipping point at which a very pragmatic process takes place in the minds of individuals: we do not want to live in an area which is ridden by violence; we want our children to grow up in a peaceful environment; we want, therefore, the violence to end. We realise, at that point, that it is preferable to accommodate the wishes of a group that does not represent us but that we nevertheless need to live with, rather than to keep fighting an idealistic – but unworkable – struggle.

To find out more, read Dr Stroschein’s book: “Ethnic Struggle, Coexistence, and Democratization in Eastern Europe” (2012), published by Cambridge University Press.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of LSEE Research on SEE, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Dr Sherrill Stroschein is a Senior lecturer in Politics at University College London and the coordinator of the MSc in Democracy and Comparative Politics. Her research examines the politics of ethnicity in democratic and democratising states, especially democratic processes in states with mixed ethnic or religious populations.