Despite having ratified increasingly sophisticated legislation on migration and asylum, many Latin American countries have applied their own laws arbitrarily in the case of mass migration from Venezuela. But new “temporary protection” initiatives in Colombia and the United States appear to recognise what the rest of Latin America needs to accept: most Venezuelans who have crossed borders are here to stay, writes Omar Hammoud Gallego (LSE Government).

Despite having ratified increasingly sophisticated legislation on migration and asylum, many Latin American countries have applied their own laws arbitrarily in the case of mass migration from Venezuela. But new “temporary protection” initiatives in Colombia and the United States appear to recognise what the rest of Latin America needs to accept: most Venezuelans who have crossed borders are here to stay, writes Omar Hammoud Gallego (LSE Government).

• Disponible también en español

Progressive legislation on asylum is close to useless if governments decide arbitrarily whether to apply it or not. But this sense of arbitrary application is precisely what we might perceive when considering the situation of the displaced Venezuelans now found all over South America.

Of the roughly 5.4 million Venezuelans displaced by economic crisis and political repression since 2015, less than 145,000 – just 2% of the total – have been granted refugee status worldwide. Latin American governments specifically have granted refugee status to less than 75,000 Venezuelans. This is nowhere near good enough.

There is a pressing need instead to emulate Colombia’s recent policy decision (followed by a similar but less generous offer in the United States) and grant long-term humanitarian protection to Venezuelan nationals who are understandably fleeing an unprecedented, government-induced disaster.

Latin American legal frameworks on asylum

But what laws can Latin American countries invoke to deal with massive inflows of Venezuelan migrants? The legal landscape around migration has changed dramatically in recent decades.

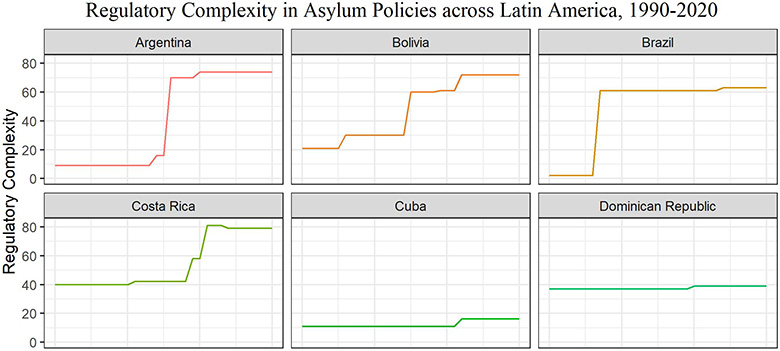

In a forthcoming study on asylum in Latin America over the last 30 years, I show how regulatory complexity – a measure of the degree of development of public policies – increased significantly in the region throughout the early 2000s (see graphs below; click to expand to all 19 states).

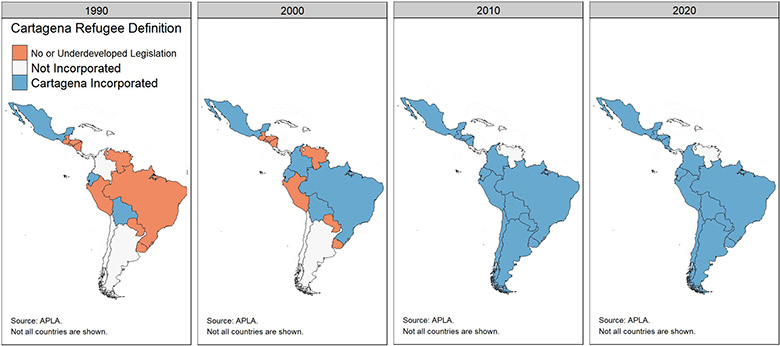

During that period, most countries adopted liberal policies on asylum that earlier scholarship – and the United Nations Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) – had praised as international exemplars of openness towards refugees. The most symbolic of these was the adoption of the Cartagena Declaration’s definition of a refugee, which goes beyond that of the 1951 Geneva Convention by including:

…persons who have fled their country because their lives, security, or freedom have been threatened by generalized violence, foreign aggression, internal conflicts, massive violation of human rights, or other circumstances which have seriously disturbed public order.

As of 2020, the only countries not to have incorporated the Cartagena Refugee Definition into their legislative frameworks were Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Panama, and Venezuela. Tellingly, aside from Cuba, which is not part of the international refugee regime, the other three countries all have a recent history of widespread immigration: Haitian migrants crossing into the Dominican Republic and Colombians displaced or emigrating to Panama and Venezuela during decades of internal conflict.

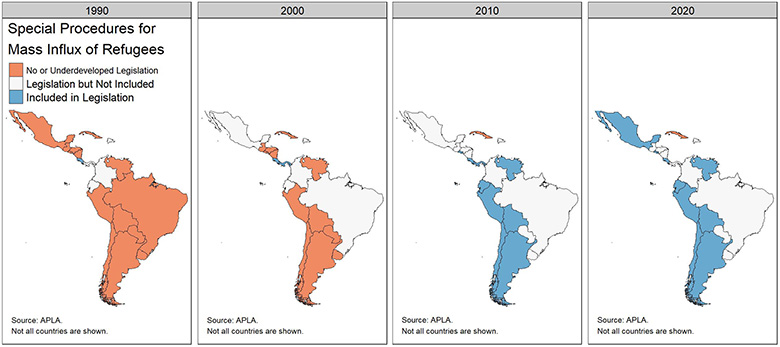

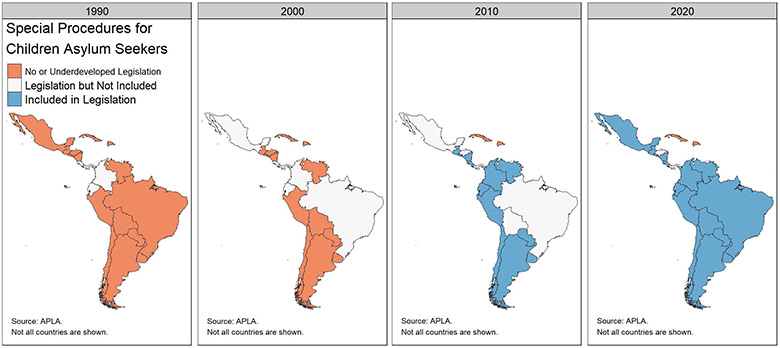

On top of an expanded refugee definition, a series of regional standards have been incorporated into the national legislation of most countries in the region.

Key amongst these were special procedures to deal with the mass influx of refugees (illustrated above) and to deal with child asylum seekers (below).

And yet, when faced with the biggest displacement of people in the history of the region, many of Venezuela’s neighbours quickly realised that their asylum systems were neither developed nor resourced enough to deal with the scale and speed of this massive inflow of migrants.

Venezuelan migration within South America

Within a few years, hundreds of thousands of Venezuelans had crossed international borders all across South America: 1.8 million crossed into Colombia, a million more reached Peru, and over 440,000 arrived in Chile and Ecuador respectively.

To deal with such high numbers, countries across South America decided to develop ad hoc migratory permits for Venezuelans instead of processing them through their normal asylum systems, as advocated by the UNHCR. One advantage of these permits – such as the Special Residency Permit in Colombia or the Temporary Residence Permit in Peru – was that they granted the right to stay, work, and access public services.

But shifting deadlines, corrupt officials, unclear rules, and stringent requirements meant that many Venezuelans either crossed borders irregularly or overstayed their temporary permits, thereby falling into irregularity.

As of March 2021, the Colombian government estimated that around 56% of the country’s 1.8 million Venezuelans were there irregularly. The total estimate of Venezuelans with irregular status in the region amounts to some one million people. It was based on this data that the Colombian government announced in February 2021 that it would establish a new Temporary Protection Status for all Venezuelans who had entered the country before 31 January 2021. This new status offers Venezuelan immigrants a 10-year residency permit, even if they had entered Colombia irregularly. Just one month later, the United States granted temporary protection status to Venezuela, giving some 320,000 of them the right to stay for an additional 18 months in the country.

Facing up to the realities of Venezuelan migration

These policy decisions by Colombia and the United States acknowledge one simple fact that other countries across Latin America need to internalise: most Venezuelan migrants and refugees who have crossed South American borders, even without regular permits, are there to stay. Allowing Venezuelans to regularise their status and settle for the long term is merely a recognition of the real state of affairs across much of the region.

While the economic and political crisis in Venezuela has been dramatic and unparalleled for a country not at war, Nicolas Maduro’s iron grip on power in Venezuela remains unchallenged. With their dire circumstances only exacerbated by the COVID-19 crisis, another 300,000 Venezuelans are expected to leave the country as soon as the pandemic is over, and many more are likely to follow after that.

Unfortunately, as of March 2021, only Brazil and Mexico – both with fewer Venezuelan migrants than many other Latin American countries – had recognised Venezuelans as refugees, thereby applying the legislation on asylum that both countries have developed over the last two decades. Peru, meanwhile, has attempted to provide some form of status to the many Venezuelans entering irregularly by letting them apply for asylum but then leaving their applications unprocessed. But despite continuing to experience widespread levels of generalised violence, it is Colombia that has set a high yet realistic benchmark for the rest of the region.

These countries have essentially two options:

- Start applying their own legislation on asylum, following Brazil and Mexico’s example, possibly through the application of accelerated procedures like granting refugee status prima facie based on nationality;

- Emulate Colombia’s initiative of creating a new migratory status that recognises the long-term nature of Venezuelan displacement, possibly by reforming existing ad hoc permits.

While the COVID pandemic has led to a substantial increase in poverty throughout Latin America, migrants face the double blow of economic uncertainty and civic invisibility, particularly where their status is irregular. Putting them back on the map is a moral imperative for governments in Latin America and beyond.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the author rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Visit the author’s website at omarhgallego.com or follow him on Twitter at @OmarHGallego

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting