Colombia’s Special Jurisdiction for Peace aims to generate pathways to justice that are acceptable both to victims and to a deeply polarised nation. If this novel and innovative institution can achieve a fair and effective form of transitional justice that encompasses truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence, the country could make a significant shift into a new phase of peacebuilding and violence-reduction, write Gwen Burnyeat (UCL Anthropology), Par Engstrom (UCL Americas), Andrei Gómez Suárez (University of Bristol), and Jenny Pearce (LSE Latin America and Caribbean Centre) following their joint hosting of a series of events with Giovani Álvarez (Chief Prosecutor of the Special Jurisdiction’s Investigation and Accusation Unit).

How to address massive human rights violations and war crimes following the negotiation of a peace agreement is one of humanity’s most painful tasks. On the one hand, the parties to the conflict are unlikely to seek to end it while faced with the prospect of long prison sentences. On the other, the victims, traumatised by loss and personal suffering, also require justice for the crimes committed against them and their loved ones.

Recognition of their experiences through concrete action is vital if they are to move forward and reconcile with the past and the perpetrators. This in turn impacts on the collective, societal prospects for taking steps towards a future with peacebuilding at its heart.

The South African Truth Commission was a turning point in acknowledging the vital importance of truth telling in peacemaking. Variants of this approach were replicated in Guatemala, El Salvador, and Peru, the latter becoming in 2003 the first truth commission to hold public hearings and recommend reforms, prosecutions, and reparations. However, the ideal balance between truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence has yet to be found.

Colombia and the Special Jurisdiction for Peace

The International Criminal Court (ICC), created by the Rome Statute in 1998, brought in new obligations in terms of addressing grave violations of human rights and international humanitarian law. As a signatory to the ICC in 2002, Colombia was the first country to negotiate a peace agreement which had to respect these obligations. The Special Jurisdiction for Peace (JEP) was thus created in the shadow of the ICC, meaning that Colombia could not offer judicial pardons for gross human rights violations; Colombian society’s right to peace instead had to be synchronised with international standards of justice.

But this is not the only reason the Colombian transitional justice process matters to the world. Colombia’s Peace Agreement in 2016 sought to end the longest civil war in the western hemisphere, which dates back to the emergence of the first guerrilla insurgency, the ELN, in 1964, and the army operation of the same year that led to the formation of the peasant self-defence groups that later became the FARC. With the demobilisation of the FARC after the 2016 Peace Agreement, the still-active ELN became the longest-lasting insurgency in the western hemisphere.

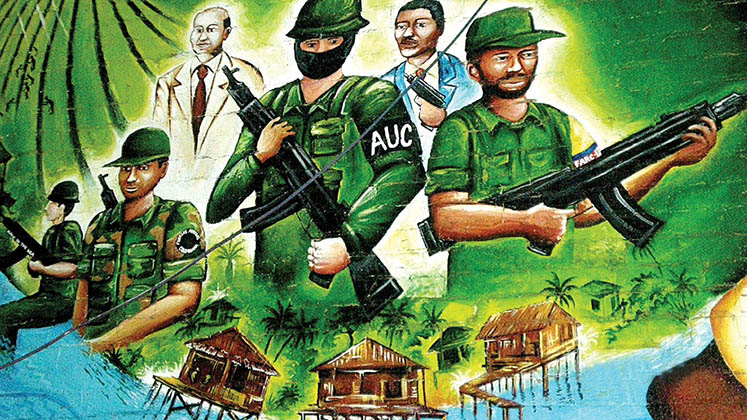

However, on top of its experience of more than ten different guerrilla groups, Colombia also has a long tradition of private counterinsurgency, including three generations of paramilitary organisations. Beyond that, a plurality of large and small drug cartels have created or sponsored death squads and taken advantage of Colombia’s fertile terrain for criminal economies. Civilians have been deeply affected, and the state now recognises almost 9 million victims, which equates to roughly 18 per cent of the population.

Given this long and complex history of violence, the task of implementing the Peace Agreement is extremely demanding, and the role of the JEP in providing justice is central to these efforts.

But the challenges faced by the JEP are exacerbated by the socio-political context of the 2016 Peace Referendum, in which the Peace Agreement itself was rejected by 50.2 per cent of the population. Although the Agreement was renegotiated and is now being implemented, polarisation continues to grow. The assassination of hundreds of social leaders and demobilised FARC members is represents a particular threat to the agreement itself.

Building on the 2005 Justice and Peace Law

If Colombia is to move into a new historical stage of peacebuilding and violence reduction, the state and the JEP will need to show their ability to generate pathways for justice that are both acceptable to victims and capable of convincing a polarised nation of their fairness and efficacy in terms of the four pillars of transitional justice: truth, justice, reparations, and guarantees of non-recurrence.

To date there have been seven peace agreements with irregular armed groups, but five of these did not include truth, reparation to victims, or punishment of perpetrators. This pattern was broken in 2005 with the Justice and Peace Law (JPL), which resulted from negotiations that enabled demobilisation of the paramilitary United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia (AUC).

For the first time, those responsible for crimes against humanity, war crimes, and genocide had to spend a maximum of eight years in prison in exchange for disarming, making reparation to victims, revealing the whereabouts of the disappeared, handing over recruited minors, truth-telling, and committing to a cessation of criminal activities.

Over 470 AUC paramilitaries received sentences for serious crimes, which is more than the number handed down by the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia or its counterpart for Rwanda. Paramilitary information led to the sentencing of over 60 congressmen/women for supporting paramilitary groups, and the remains of 4,300 of the forcibly disappeared were identified. Nearly 11,000 victims of paramilitary groups received reparations.

That said, state actors and civilian third-party groups were not part of the process, and some paramilitary commanders continued with their criminal activities from prison. The 2005 JPL also failed to offer holistic reparations or to fully investigate gender-based and sexual violence as a weapon of war.

The Special Jurisdiction for Peace and the Investigation and Accusation Unit

The Havana peace negotiations took these lessons into account when the JEP was designed. The negotiations also drew substantively on transitional justice theory and on the experiences of other countries. The JEP forms part of the transitional justice component of the Peace Agreement, known as the Comprehensive System for Truth, Justice, Reparations and Guarantees of Non-Recurrence. This is the first such system to take on board the holistic approach advocated by transitional justice theory, which seeks to pave the way for national reconciliation through restorative justice.

Two pathways were established for parties appearing before the JEP.

The first, the dialogic process, resolves cases in the Chamber for Recognition of Responsibility. Access to this process depends on fulfilment of the JEP’s four requirements: contribution to truth-telling, recognition of responsibility for crimes committed, compliance with provision of reparations to victims, and commitment to non-recurrence. This process gives victims the opportunity to participate in the process and engage directly with the perpetrator, thus paving the way for restorative rather than retributive justice. It ends with an alternative, non-prison-based sentence.

The second, the adversarial pathway, involves the Investigation and Accusation Unit (IAU). This body is responsible for investigating those who do not fulfil the four requirements, and it can refer cases to JEP magistrates for trial, where defendants can ultimately receive jail sentences of up to 20 years if they fail to acknowledge their responsibilities before a verdict is reached. In essence, the IAU is the JEP’s dissuasive arm, aiming to encourage perpetrators to accept the dialogic process and build towards national reconciliation.

The JEP has a 15-year mandate. It is comprised of five bodies: three chambers, a Special Tribunal for Peace, and the IAU. Together, these different bodies perform various important functions:

- granting amnesties to FARC ex-combatants that have not been charged with grave crimes

- receiving state agents and third parties that voluntarily apply for their cases to be considered by the JEP

- reviewing the cases of those who already have cases open against them or are serving sentences handed down within the ordinary justice system

- enabling dialogic processes for parties to recognise their responsibilities for crimes committed directly or indirectly in the conflict

- issuing sentences

The JEP is autonomous and independent; the ordinary courts cannot appeal decisions made by the JEP. Its magistrates and the chief prosecutor were elected by an international selection committee created via the peace agreement.

The IAU is the only component of the JEP with a team of judicial police investigators as well as a team of forensic experts. It also has special teams for investigating cases of gender-based violence, for ensuring an ethnically sensitive approach, and for issuing protection orders for threatened victims, witnesses, and parties under investigation. The fact that the IAU has ten regional offices is particularly important, as the majority of victims live in rural, hard-to-reach areas.

The JEP and hope: navigating the complexities of post-war Colombia

The JEP, and in particular the option of non-prison-based sentences, has been at the heart of public controversy. Having been elected in 2018 on a promise to substantially modify the Peace Agreement, President Duque himself has objected to the statutory law that governs the JEP. This act, unprecedented for a head of state, undermined the legal security of those intending to appear before the JEP, even if his objections were ultimately overruled by Congress and the Constitutional Court.

The JEP is currently examining the cases of 12,481 people: 9734 former FARC members, 2640 members of the armed forces, and 95 other state officials. The JEP must also decide whether or not to accept more than 900 third parties that have so far applied to enter the jurisdiction.

The JEP has prioritised seven “macro-cases”, including the investigation of kidnappings committed by the FARC, extrajudicial executions committed by the armed forces, and the impact of the armed conflict on ethnic communities in the Pacific region. In 2020, the third year of the JEP’s existence, we should begin to see the results of these investigations.

Challenges for the Special Jurisdiction for Peace

There are, however, numerous challenges facing the JEP:

- Protecting victims, witnesses, and defendants

Assassinations of ex-combatants have happened in the wake of all previous peace negotiations in Colombia. The latest report of the UN Verification Mission in Colombia found that 173 FARC ex-combatants and 303 social leaders had been killed between the signing of the Peace Agreement and the end of 2019, some by members of the army. These assassinations reduce the probability of victims coming to know the truth and create fear amongst ex-combatants, providing a fertile climate for a possible return to arms. So far, the IAU has analysed over 90 risk situations and ordered that 46 protection schemes be assigned to victims and defendants. - Achieving greater legitimacy amongst the wider public

If the JEP’s sentences – whether alternative or carceral – are to contribute to its holistic vision of transitional justice and pave the way for national reconciliation, it needs to promote a climate favourable to popular support for its decisions. The chief prosecutor understands that legitimacy must be won from a diversity of groups with divergent opinions. Strengthening coordination with other state institutions is also crucial, given the well-known propensity in Colombia for inter-institutional coordination failures in policy implementation. The JEP also needs to show convincing results quickly even though transitional justice processes are complex and tend to take time to achieve their aims. The process involves, after all, thousands of crimes and many hundreds of perpetrators. - Creating mechanisms to prioritise cases of gender-based violence

The IAU has helped 598 victims of sexual violence to present evidence to the JEP, as well as designing software to process and analyse such cases (LAYNA). This platform has so far registered 1,400 allegations of criminal actions, and other state bodies are able to use this information to prevent victims from having to repeatedly narrate their harrowing experiences. In this way, the JEP can give real visibility to these crimes in Colombia while avoiding revictimisation, which is especially important given Colombia’s context of social normalisation or minimisation of sexual violence.

Overall, Colombia’s Peace Agreement remains fragile. Yet despite a ticking clock and a backdrop of public scepticism, threats, and real violence, institutions such as the JEP and the IAU continue to make significant efforts to achieve a lasting peace.

The Colombian case reveals the need for transitional justice processes to be situated analytically in their social and political contexts. These processes do not happen in vacuums but rather in societies already divided both by years of violence and by social rifts with complex historical trajectories.

In the midst of the many complexities of post-war Colombia, the JEP is a process of global importance. Despite having to defend their independence from political interference, the JEP’s staff continue to strive to take this unique opportunity to end half a century of war with justice yet without retribution. This kind of reconciliation – and the end of Colombia’s longstanding cycle of war and violence – could serve as a model for the many countries around the world still struggling with their own situations of conflict and post-conflict.

Notes:

• The views expressed here are of the authors rather than the Centre or the LSE

• Please read our Comments Policy before commenting