The recent proliferation of border studies that accentuate the surreality of the DMZ as an empty no- man’s-land often contributes to this perception that has sustained and developed over time. With so much focus on the border itself, however, everything else around it seems to get neglected. And often, desperate to find something different or unique about this border condition, it fails to inquire deeper into the everyday life of the people living in the frontier. From the very onset of my field work, it was clear that the views of the frontier and its associated villages were radically different between the state and those who live there, writes Alex Seo.

_______________________________________________

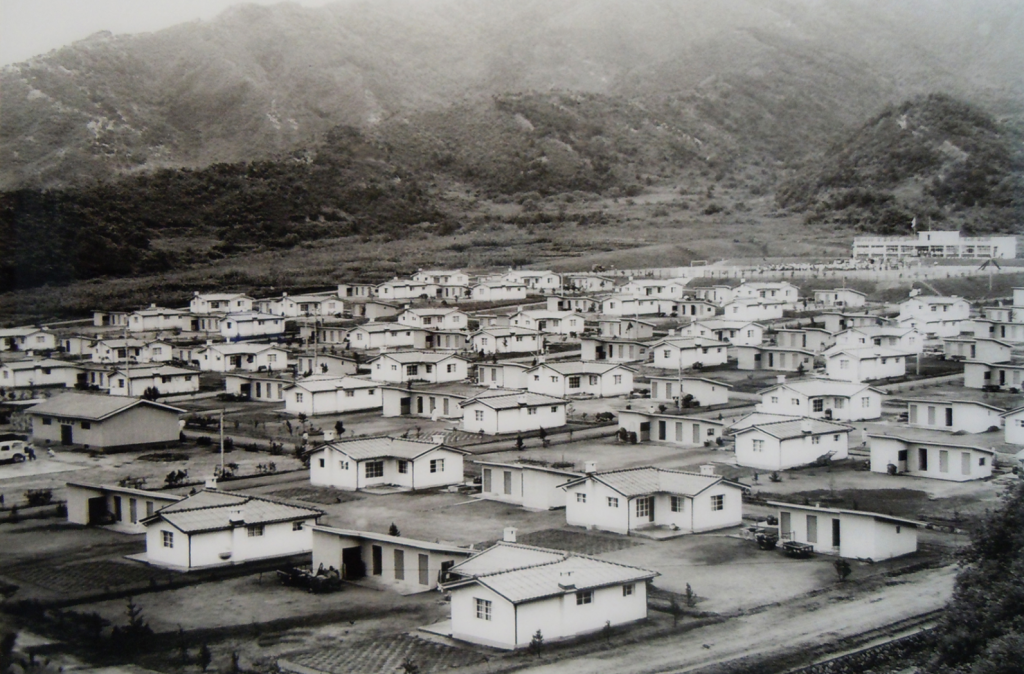

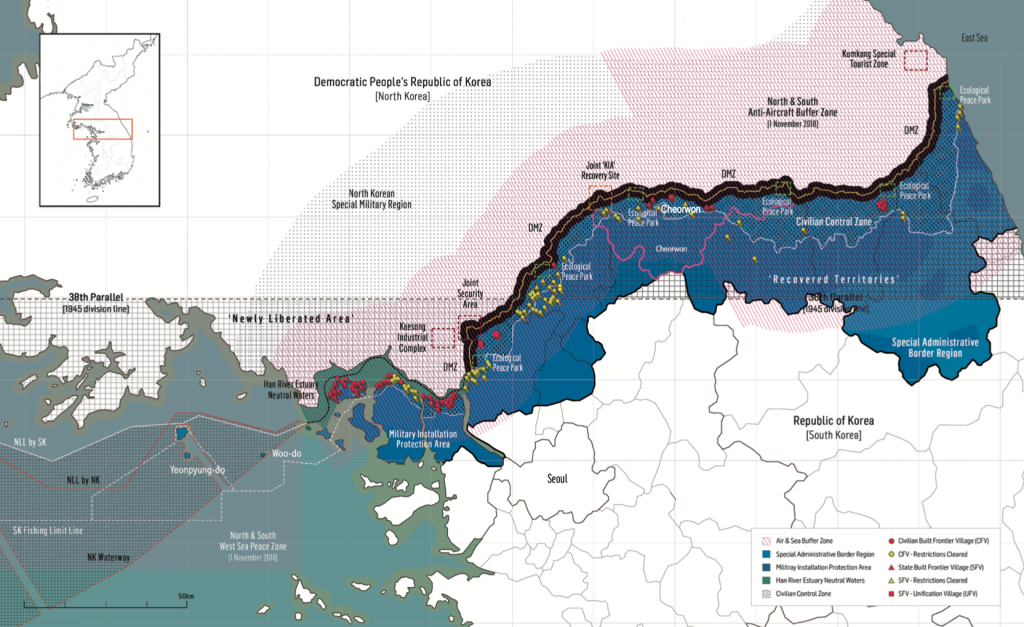

Along the length of the Inter-Korean border, within the visible proximity from North Korea, a series of South Korean frontier villages stand abutting the Demilitarized Zone (see Figures 1, 2 and 3). Constructed shortly for the Korean War (1950-1953) for the purposes of security, territorial governance and propaganda, the frontier villages and the life of its residents – or subokmin – embody a long history of devastation and violence (Seo, 2020). Due to their location of residence in what used to be North Korean territory before the War, and their history as War refugees, subokmin received both praises as well as suspicions questioning the validity of their citizenship: identified as a somewhat marginalised group of population (Hahn, 2017).

Their existence, however, remains largely unknown for a number of reasons. On the ground, the villages’ geographic proximity to North Korea and the extreme level of security imposed by the South Korean military restrict access and mobility of those who go in and out of the region (see Figure 2 above and Figure 4 below). On another level, the general tendency to consider the border as purely a politico-militaristic problem has rendered the space of the border merely as a ruin: ‘a last remaining relic of the Cold War’ (Kraythammer, 2017). As such, the majority of responses I received while undertaking my research, indifferent to same gaze shone on subokmin, was that of curiosity and suspicion: “Why go there?”. But with a surprisingly large presence of human habitation in the South Korean borderlands, the particularities of Korean border society became an integral part of the analysis should one wish to better understand this complex border (Gelézeau, 2013). My PhD research, therefore, revolved around a different question: why is so much still there?

The problem for conducting fieldwork with a new set of questions in mind, as good as it may sound, is that there are very few precedents to follow. This makes the planning of fieldwork or adopting a method of analysis an arduous task. The DMZ, being a highly politicised environment where spatial conditions could quickly dilapidate – both from a local event (a gun-shot or border crossing) and from a distance (Seoul and Pyeongyang) – makes it incredibly difficult to even vaguely predict the outcome of the research. For instance, in August 2015, a land-mine explosion at the border (seriously injuring two South Korean military officers) had halted all access to the border for more than three weeks. It was then followed by an implementation of enhanced border security measures: roads were closed; visitors had to wear colour coded bibs and were to enter the border region strictly after sun-rise and exit before sun-down. In this context, my chosen research methodology, instead of being aimed at overcoming restrictions, had to be able to adapt and work with those restrictions.

While the focus of my research was clearly aimed at a better understanding of human habitation in the hostile border that experiences high levels of conflict, I could not impose a rigid or narrow methodological framework from the outset. Instead of conforming to a primary method or one source of information, I had to incorporate multiple methods of analysis, which stemmed from certain limitations and restrictions that were evident from the start of the project. Firstly, there was very little precedent research concerning human habitation in the inter-Korean border, thus the work required an open-ended approach in order to establish new frameworks within which the research could be conducted. Second, being a volatile area of study, the research methods had to be sufficiently diverse in order to react to any abrupt changes and unexpected events that were characteristic of the ongoing research. Thirdly, the abrupt and unexpected nature of the border, at the same time, became a fundamental aspect of the research. This made it unfeasible and impractical to describe the research constraints in advance and to isolate the factors to be studied, as methodologies in the discipline of Architecture frequently respond to the ‘found’ conditions of a physical site that constitute it as a ‘situation’, for example in a village (Conflict in Cities, 2012).

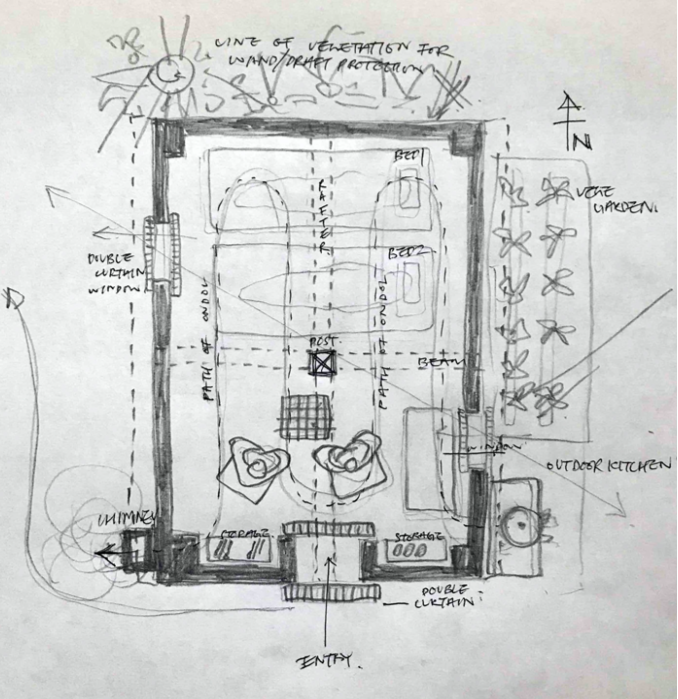

With an emphasis on the ‘spatial’ and ‘physical’ aspects of the border, the empirical field research adopted a variety of techniques for visual and spatial analysis. While the archival work (essential for understanding government policies) allowed the villages to be studied as an official part of the South Korean state-building process (Seo, 2018); in situ work of site observation, mapping, photography, video documentation, survey, and architectural analysis of different forms of habitation allowed the border to be examined as a lived space, relying on the experiences of its current residents (see Figure 3 above and Figures 5 and 6 below). As a matter of fact, because of the scarcity of photographs and detailed maps of the region due to military screening, mapping proved to be a highly valuable exercise on its own: while it was forbidden to take photographs facing the North, making sketches were considered acceptable for an unknown reason. In addition, the documentation of personal memories were also paired with 43 semi-structured in-depth interviews with 31 residents in three frontier villages, as well as Cheorwon’s present and former community leaders, local historians, military and government officials over four entries to South Korea and six site visits between 2015-2018 (Seo, 2020).

The decision to arrange a series of site visits was threefold. First, drawing from a broad spectrum of existing studies of the South Korean border region as a guide, the first field research (June–September 2015) attempted to cover the whole length of the South Korean side of the border region beginning from the islands of the west coast and travelling to the eastern border. The initial field work not only confirmed the highly dynamic nature of the border, it helped to narrow down and confirm possible sites that allowed physical access to conduct a more detailed site analysis and a proficient number of archival documents available for further research: different types of frontier villages in Cheorwon County.

Second, visits to the frontier villages over different seasons provided a more wholesome picture of everyday life at the border. How the villagers go about their daily life – the tasks at hand and how they would occupy the space of the village – is seasonally varied. The six visits undertaken at different times of the years (2015-2018) helped to reveal subokmin’s multitude ways of coping with the conditions at the frontier that may be identified during a particular season but go unnoticed on another. For example, obtaining physical access to the frontier villages at a day to day basis proved to be a particularly dubious task. Often, the access to the villages will be granted on one day and denied on another. While my purpose of visit remained the same, the officers in charge of the checkpoint did not. More often than not, the screening process and its results were dissimilar. One officer may simply ask for one form of identification and give access, while another may ask to provide several identifications or bombard with questions about one’s motive for the visit before rejecting entry. At times, therefore, it required meeting the villager at the checkpoint or to visit the checkpoint with a local familiarity to secure access for the day, which is not easy to arrange without a personal connection, since the area is not open to public.

Lastly, if obtaining physical access to the frontier villages at a day to day basis was a formidable task, familiarising oneself with the villagers was an important undertaking that required patience. In my first visit to Cheorwon between 18-25 August 2015, the majority of subokmin remained highly alert and suspicious about the purpose of research. Understandably, subokmin were those who had spent most of their waking hours in power-laden situations in which a misplaced gesture or misspoken work can bring about terrible consequences. While the villagers seemed reluctant in sharing their stories, they were, at the same time, curious to know who the audience of the research is, how long it will last, what it intends to analyse, and what it hopes to achieve. Many of the villagers expressed disappointment towards earlier cases of one-off interview sessions that looked to question them instead of taking time to listen to what they had to say. More often than not, the interviews ended with the villagers asking, “Will you be back some time?”.

The series of regular visits made across many years allowed me to develop a more personal relationship with the villagers or certainly their kindness to adapt better to me than I to them. In my first visit to Cheorwon in June 2015, I was able to familiarise myself with the village leaders, County officers and local scholars who would assist me most arduously in gaining military permission to enter the border region and setting up interviews with the knowledgeable members of the frontier community over the whole course of this research. By my third visit in January the next year, several frontier villagers who were also acting as a local tour guide began to volunteer to assist with the research by giving out and collecting a survey questionnaire to the outside visitors. From the third visit and onwards, what was merely a rigid question and answer sessions carried out on the side of the road or at an insignificant café became a friendly dialogue over tea or lunch which the villagers hosted within the boundary of their own home. In other occasions, the villagers would happily take me to more personal sites of elation and memorial, though more often, devastation and grief. Amidst a variety of ‘conversations’ were a host of insightful stories such as their misdeeds, smuggle and concealed emotions I had not come across in my earlier ‘interviews’. These include stories of subokmin and a number of South Korean soldiers making daily trips to the water reservoir located inside the DMZ ‘under the radar’ for the purposes of ‘water tapping’ due to the scarcity of water to provide for their rice-field.

The mixed methodology research of frontier villages enabled the specific spatial, social and political aspects of the frontier village to be studied as a real, physical space of the everyday life. Flexibility of methods and a sense of trust between the researcher and those being observed becomes a critical aspect of research in the areas of conflict and extreme surveillance. Such an approach, I believe, is important in its ability to help break from the conventional focus on the border as explicit sites of devastation, war time relics and contested political histories, to all that is still there and significance this has for the people who call it their home. In my five years at the border known for its hostility, I found villagers who were forgiving of my inevitable mistakes, who became tolerant of my curiosity, overlooked my incompetence, and even invited me to work beside them on their precious vegetable garden and rice paddocks. This research, therefore, I suspect, is more the product of its subjects than most village studies.

References

Hahn, M. (2017). Korean War and the Recovered Territory. Seoul: Blue History (In Korean).

Kim, H. (2008). Thinking about Methodology of the Unification Research: Evolution, Disputed Issues and Subjects. Journal of Unification Policy Studies 17(2): 203-231.

Kraythammer, C. (2017). Cold War relic, present day threat. The Washington Post, 5th January. Retrieved from: www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/global-opinions/cold-war-relic-present-day-threat

Gelézeau, V. (2013). Life on the Lines: People and Places of the Korean Border. In V. Gelézeau, K. Ceuster, & A. Delissen (eds.), De-Bordering Korea: Tangible and Intangible Legacies of the Sunshine Policy, pp. 34-67. London: Routledge.

Seo, A.Y.I. (2018). From Orderly Dispersion to Orderly Concentration: Frontier Villages at the Korean Border 1951-1973. Scroope: Cambridge Architecture Journal 27: 43-58.

Seo. A.Y.I. (2020). Constructing Frontier Villages: Human Habitation in the Korean Borderlands after the Korean War (Ph.D. dissertation). University of Cambridge, UK.

Conflict in Cities and the Contested State. (2012). Retrieved from: www.conflictincities.org

For citation: Seo, A. (2020) Travels to the DMZ: Conducting Fieldwork in the Inter-Korean Border. LSE Field Research Method Lab (28 October 2020) Blog entry. URL: https://blogstest.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/2020/10/28/conducting-fieldwork-in-inter-korean-border/